How Ross Perot Paved The Way For Trump

A nationally known tycoon with a boastful personality, a penchant for tough talk, an aversion to illegal immigration and free trade, and a contempt for Washington norms: Before there was Donald Trump, there was Ross Perot. His two presidential campaigns planted seeds that would bear poisonous fruit 20 years later.

Perot, who died Tuesday, was the improbable candidate in 1992. Entering as a third-party challenger against President George H.W. Bush and Gov. Bill Clinton, he captured the spotlight and soon led in the polls. Despite pulling out in July, only to reenter in October, he got nearly 19 percent of the vote, the strongest showing by a non-major party candidate since 1912. Running in 1996 as the nominee of the Reform Party, which he founded, he got 8.4 percent of the vote.

In his races, Perot provided a road map for a populist charlatan to reach the White House. He was an unconventional candidate peddling crude and shallow solutions, many of which bear a strong resemblance to what Trump would later propose. Consciously or not, Trump borrowed liberally from Perot’s formula in his own campaign, and he made it work.

The parallels are many. NAFTA was a terrible deal? Perot fulminated against it in 1992. Stop spending money protecting our allies? Perot had the same idea. Slap tariffs on our biggest Asian trading partner for its unfair practices? Trump has gone after China the way Perot threatened to go after Japan.

Trump threatened to “send in the feds” to stop crime in Chicago, which apparently meant deploying the National Guard. Perot’s idea was to “declare civil war and the drug dealer is the enemy.”

Perot didn’t make the blatant appeals to white racism that Trump does. But in 2000, his Reform Party nominated someone who did. Pat Buchanan extolled the Confederacy, warned that immigration would make America “a Third World nation” and earned the praise of neo-Nazi David Duke. Trump is what you would get if you blended Perot and Buchanan over high heat.

Serious policy ideas are not the essence of Trumpism or Perotism. What distinguished the Texas computer magnate — who was the self-made billionaire Trump pretends to be — was his glib, cocksure manner, suggesting that all problems would yield to the blunt hammer of his common sense. After years of watching career politicians fall short, Americans were taken with his claim that a savvy business mogul would do better.

Like Trump, Perot was thin-skinned and given to bizarre fantasies. At one point, he whined bitterly, “The Republicans have had a nonstop saturation bombing to recast my personality.” He withdrew in 1992, he said, out of fear the GOP would smear his daughter and ruin her wedding.

Trump promised to “drain the swamp” in Washington, much as Perot vowed to “take out the trash and clean out the barn.” Trump’s demand to “remove bureaucrats who only know how to kill jobs (and) replace them with experts who know how to create jobs” sounds like it was plagiarized from Perot.

Like Trump, Perot had no appetite for complexity or details. His idea for education? “Let’s stop having two-day summits for governors that don’t amount to anything, and let’s get down to blocking and tackling and fixing it now.” The tax code? “No. 1, it’s got to be fair. No. 2, it’s got to raise revenue.”

Politicians, in his mind, were guilty of overthinking. “I’ve got a lot of experience in not taking 10 years to solve a 10-minute problem,” he bragged. Trump talks in exactly the same way, offering simplicity spawned by ignorance.

Perot did have a positive impact on the federal budget deficit. He laid out a bold plan to eliminate it, including tax increases and spending cuts that included both entitlement programs like Social Security and Medicare and the military budget.

When Clinton became president, he was forced to take steps, in concert with Republicans in Congress, that yielded a surplus. Without Perot, it might not have happened.

Trump said he would not only balance the budget but pay off the entire national debt in eight years. But unlike Perot’s budget promises, Trump’s were utterly fraudulent. He signed a tax cut that was guaranteed to boost a federal debt that was already on a soaring trajectory.

For the most part, though, Perot was a false prophet, relying on glib bromides, a pugnacious attitude and a disdain for the compromises and trade-offs that democratic government requires. In 1992 and 1996, we managed to resist the coarse nativist demagoguery being offered. In 2016, we succumbed.

Steve Chapman blogs at http://www.chicagotribune.com/news/opinion/chapman. Follow him on Twitter @SteveChapman13 or at https://www.facebook.com/stevechapman13. To find out more about Steve Chapman and read features by other Creators Syndicate writers and cartoonists, visit the Creators Syndicate website at www.creators.com.

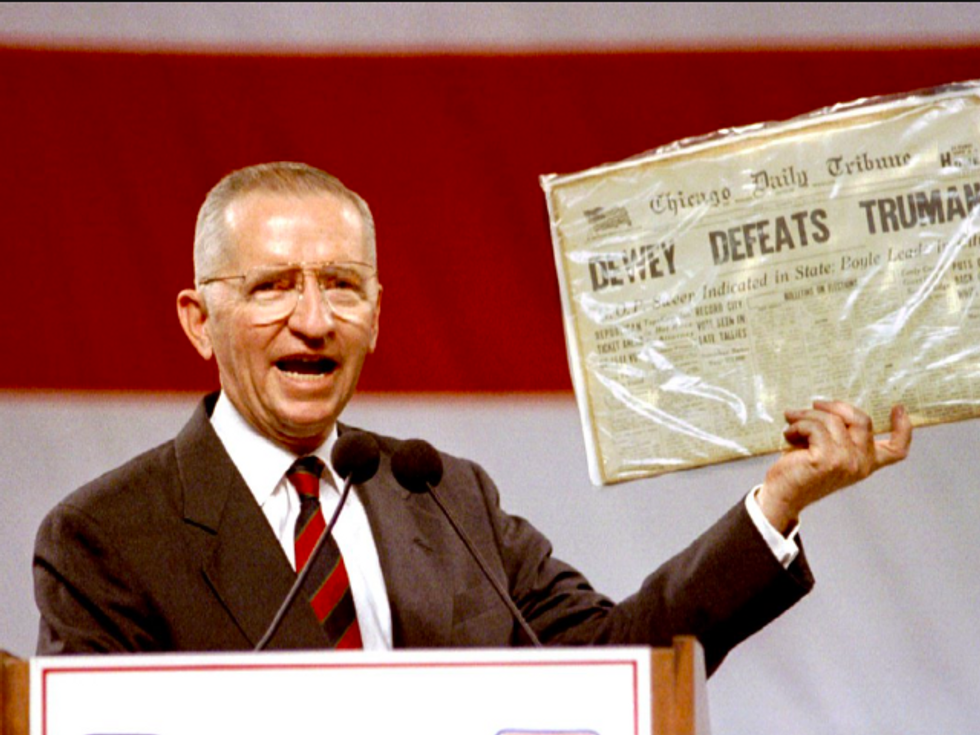

IMAGE: Texas billionaire and Reform Party presidential candidate Ross Perot.