Aborted Stem Cells Produced Trump's 'Miracle Cure' For Covid-19

When Donald Trump went to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center for treatment for the coronavirus, he benefited from a treatment that's not yet available to the public.

The antibody treatment from Regeneron, which Trump is now claiming "cured" him without evidence, has yet to be approved by the Federal Drug Administration. It's also derived from stem cell research.

That might be unremarkable but for the fact that Trump's administration has done everything it can to block research that relies on stem cells and fetal tissue. Trump's anti-abortion evangelical base is deeply opposed to research that relies on either of these because they have a tenuous connection to abortion.

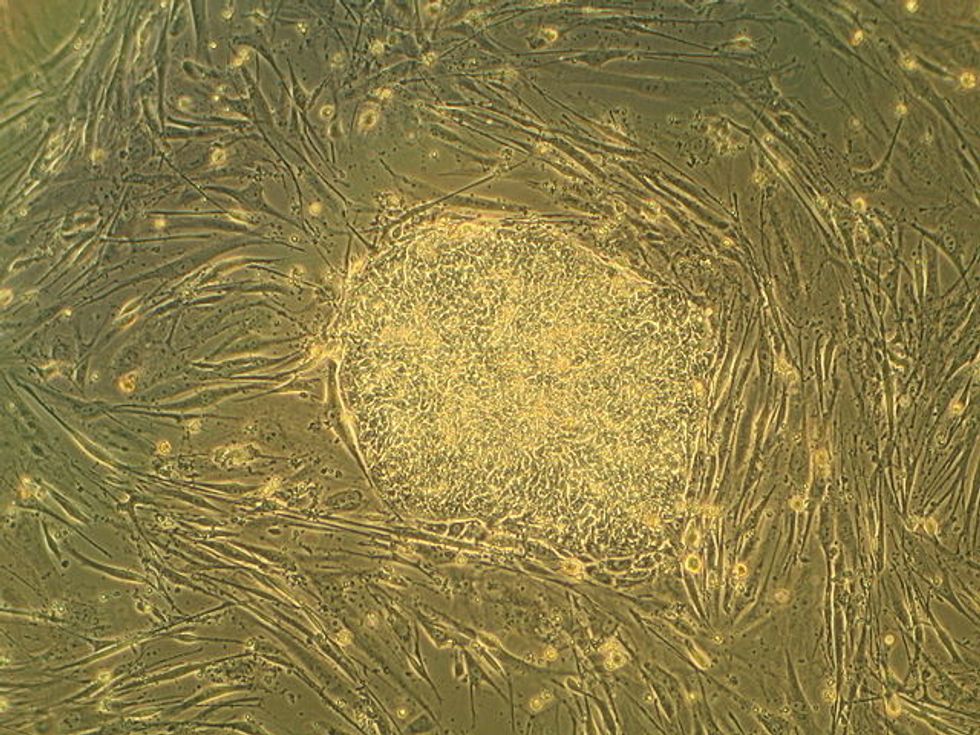

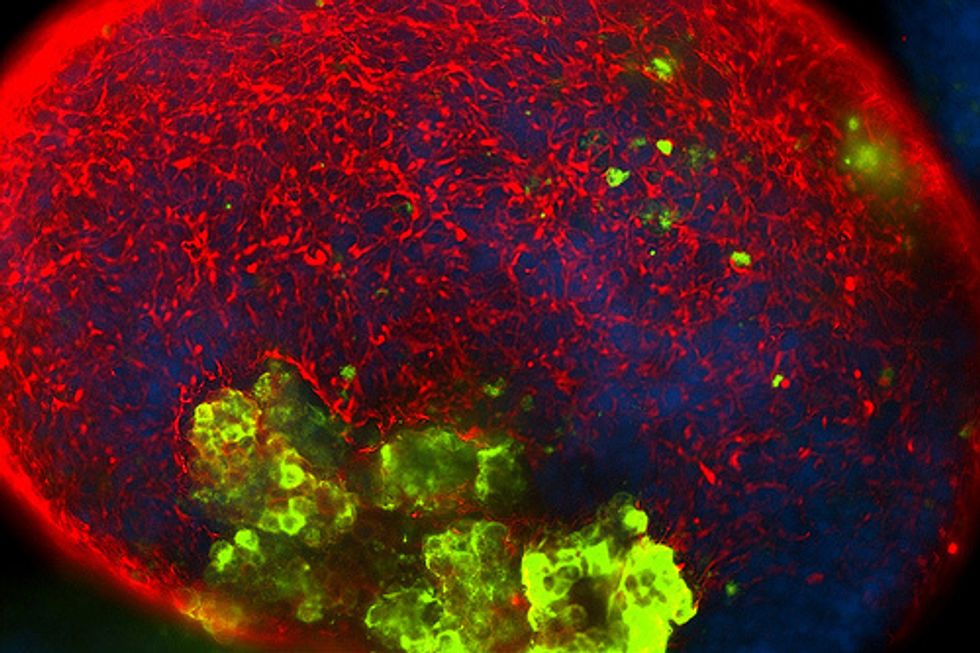

Regeneron's embryonic stem cell line was cultured from fetal tissue from an abortion. Fetal tissue research uses material that would otherwise be discarded and is obtained with the consent of people who have abortions.

Just last month, a group of 94 anti-abortion legislators thanked Trump for "his efforts to support pro-life policies" and requested that he "end taxpayer funding for human embryonic stem cell (hESC) research at the National Institutes of Health (NIH)." The group's press release said there was no proof of a "single patient's life being saved through embryonic stem cell treatments."

Similarly, James Sherley, who works for the anti-abortion Charlotte Lozier Institute, said any fetal tissue research is unethical if it "even in a small part contribut[es] to motivating elective abortions."

In 2018, a workshop at the National Institutes of Health concluded that fetal tissue research was the "gold standard" for many critical studies. In response, Marjorie Dannenfelser, president of the anti-abortion Susan B. Anthony List, said federal officials who promised fetal tissue research would continue were "out of step with the President's pro-life agenda" and that fetal tissue research "involve[d] harvesting the body parts of unborn children from induced abortion."

Dannenfelser and other anti-abortion activists prevailed. The administration created a Human Fetal Tissue Research Ethics Advisory Board composed mostly of people who have publicly opposed fetal tissue and embryonic stem cell research. The board voted to reject 13 of 14 applications.

This extremely restrictive view is shared by Amy Coney Barrett, Trump's nominee to replace Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the Supreme Court. She's on record calling for doctors to be prosecuted for discarding unused or frozen embryos.

At the beginning of the coronavirus outbreak, an NIH researcher appealed to top officials to use fetal tissue to research potential coronavirus treatments. There's no record that he was ever allowed to do so. The researcher worked at the same laboratory, the Rocky Mountain Lab, where in 2018 the Trump administration put a halt to HIV research that would have used fetal tissue. The ban on fetal tissue research also hamstrings vital Alzheimer's and cancer research.

Even as he promises that hundreds of thousands of doses of Regeneron will be available, Trump has continued to rail against abortion, tweeting that Democrats are "fully in favor of (very) LATE TERM ABORTION, right up until the time of birth, and beyond—which would be execution." Last month, he went after Virginia Gov. Ralph Northam, saying that Northam, a Democrat, "is in favor of executing babies after birth."

Democrats do not favor abortion up until the moment of birth, nor do they favor executing babies.

It seems Trump is comfortable discarding his high-profile antipathy toward stem cell and fetal tissue research when it benefits him.

Published with permission of The American Independent Foundation.