By Kate Linthicum, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

LOS ANGELES — Just after sundown, a woman peeks into Room 209.

Fouad Wawieh and his family appraise her warily. The woman, a resident of this one-star motel on Pomona’s rough north side, gestures sloppily for a cigarette. Fouad, who has been chain-smoking Egyptian cigarettes while chopping cucumbers for a salad, walks over and offers her one. His wife, who is preparing beef, rolls her eyes.

Safaa doesn’t like this woman, who looks strung out on drugs. She doesn’t like this kitchenette either, with gas burners so weak it takes hours to prepare a traditional Syrian stew.

This is the family’s third week living in two cramped rooms at the American Inn & Suites, and their third week in America. Refugees from Syria who fled a comfortable life in the suburbs of Damascus, they’re trying to make sense of this strange first chapter of their new life.

Compared with many other Syrians, Fouad and Safaa are lucky. They lost all their possessions and dozens of friends and family members in Syria’s bloody civil war, but they managed to escape unharmed to Egypt with their six children.

They did not join the hundreds of thousands of their displaced countrymen walking through Macedonia, Serbia and Hungary, dodging land mines, tear gas and water cannons on their way to uncertain asylum in Europe. They did not fall from a capsized fishing boat and drown in the Mediterranean Sea.

Instead, fortune struck: In Cairo, the Wawieh clan was selected at random by the United Nations to be resettled in the United States, which accepts tens of thousands of refugees from around the world each year. They ended up in Pomona because a friend of a friend was living there.

But lucky isn’t the same as easy.

After bloody terror attacks in Paris, anti-refugee sentiment has spread across the U.S., with members of Congress calling for drastic new controls on the admittance of Syrian refugees. More than half of the nation’s governors have said they will refuse to allow Syrian refugees to settle in their states, citing concerns over security.

Knowing that makes Fouad weary. But he and his family have more immediate concerns, like trying to coax their tongues around an ungainly new language and searching for jobs and a permanent home. Safaa, a wry woman whose light hazel eyes contrast strikingly with her black hijab, refuses to let the hotel staff clean the rooms, preferring to make the beds and scrub the floors herself.

When they arrived in the U.S., a nonprofit contracted by the government paid their first month’s rent at the motel and issued them checks amounting to a little more than $1,000 for each family member.

The agency will help them for 90 days, then they’re on their own.

Before coming to America, Fouad and his family were vetted for 18 months by officials at the U.S. Embassy in Cairo. Along with the security screenings, medical tests and interviews, they were required to take a cultural orientation class.

In one exercise, they were asked to write their names on a piece of paper using their right hand. Then they were asked to try again, this time holding the pen with their left.

That’s how life is going to be in the U.S., the teacher explained. It won’t be under your control.

One day soon after arriving, Fouad catches a ride from the motel to a modest brown stucco house with a “for rent” sign out front. A gregarious man with thinning black hair, Fouad hops out of the car and swaggers confidently to meet the owner.

The man looks up and shakes his head.

“I had three applications, and you know what, I already accepted one,” he says.

Fouad nods. Rejected again. He doesn’t blame the landlord for not wanting a tenant with no job and no credit.

On the ride back to the American Inn, Fouad shakes off the disappointment by cracking jokes. It’s the same thing he does when he and his wife go grocery shopping and struggle to locate even a bag of sugar.

“It’s the only strategy I have,” he says. “You have to realize you’re just a newborn here, and try to learn the fundamentals.”

Life was so much better back in Syria, before President Bashar Assad’s violent suppression of anti-government protests plunged the country into civil war.

Fouad was a successful sheep rancher in Douma, a wealthy suburb north of Damascus, and lived in an apartment building owned by his parents, who occupied the bottom floor. He never left without stopping to give his mother a kiss.

They had a country house too, with a rose garden and a pool where he taught his children how to swim. It was all destroyed by Assad’s rockets.

These days, Fouad sits with his family beside the dingy motel pool, scrolling through photos of home on his smartphone as palm trees rustle in the hot Santa Ana winds. He hits record and films his sons cannonballing into the water.

Then he sends the video to relatives living in Turkey, Belgium, Saudi Arabia and other distant points of the growing Syrian diaspora.

He despised the police state. Growing up under the strict rule of Assad’s father, Hafez, Fouad was warned from a young age that “even the walls have ears.”

But he preferred playing cards to talking politics. So when the Arab Spring came to Douma, he kept his head down and focused on his business.

His oldest son was different. Thin, with his father’s strong nose and pouty lips, Omar was 15 and eager to test limits.

When demonstrators filled the streets, calling for Assad’s ouster, Omar joined them. Security forces sometimes beat him black and blue. When other protesters began disappearing, his mother took to locking him inside their home after Friday prayers, when most of the rallies were held.

Safaa had just given birth to Massa, her sixth child.

“I don’t want troubles,” she said.

By then the city was under siege. Barrel bombs screamed from the sky, converting entire residential blocks into smoking piles of rubble. After the explosions, shell-shocked survivors would wander through the dust, calling out to God as they stepped over bodies.

One day a warhead hit the Wawieh house. Miraculously, everybody survived. But it was a sign that they had to leave.

Fouad made the fateful decision in 2013. They were living in a small house with two other families, sleeping in shifts because there wasn’t enough space on the floor. He worried that his eldest daughters were on the verge of nervous breakdowns.

He handed over most of his money to a smuggler. They left the remains of Syria one morning before the sun rose.

In Cairo, where they settled with the help of an Egyptian nonprofit, Omar went to work with his father and younger brother and soon found himself in the throes of another teenage fixation: love.

She also was a Syrian refugee, with powder-white skin and radiant dark eyes. As is custom, they spent time together in the company of friends, walking Cairo’s crowded streets and shopping malls. She was so devastated when he left for the U.S. that she refused to see him off.

He dreams of bringing her to the U.S. But for the time being, their relationship unfolds only on WhatsApp.

“My Love.” That’s how her name is saved in his phone.

Omar doesn’t know much English beyond that phrase, which makes finding work hard. His younger brother and sisters, enrolled at public schools in nearby Claremont, are picking up the language quickly — learning important words like “iPad,” “Halloween” and “pizza.”

The afternoon call to prayer rings out and the worshippers bow en masse, touching their foreheads to the plush green carpet.

The imam at the Islamic Center of Claremont is talking about Islamophobia: bigotry directed against Muslims. “We are not inferior,” Mohamad Nasser tells the hundreds gathered here for Friday prayers, the women separated from the men by thick gold curtains. “We are the best thing that happened to America.”

After the Paris attacks, some of Fouad’s friends in Europe have been heckled in the street. But he doesn’t worry much about racism or religious intolerance in the U.S. “If they didn’t want us, they wouldn’t have brought us,” he says.

The mosque and its parishioners from far-flung countries including Afghanistan, Sudan and Malaysia are a source of comfort for the Wawieh family. A Filipino family donates a used Trail Blazer. A Pakistani man offers Omar an internship at his computer repair shop.

Mahmoud Tarifi, who grew up in Lebanon, takes turns with his wife ferrying Fouad to appointments and the children to school.

One day he gets a tip that a Palestinian-American building contractor is looking for workers. So he drives Fouad and Mustafa Kanjon, another Syrian refugee looking for a job, out to a new condo project the man is building in Fontana.

The contractor, Shareef Awad, takes an immediate liking to Kanjon, who worked as a carpenter in Syria and in Jordan, where he fled with his family when the war broke out.

Awad explains that he too arrived in the U.S. penniless and offers Kanjon an entry-level job as a laborer. He vows to help him move up at the company and eventually get his own contractor’s license and his own big pickup truck.

Fouad tells Kanjon he’s lucky. “I’d take any job,” he says, gesturing to the street. “I’d lay asphalt.”

Fouad tries to stay positive for his wife and children’s sake, but all this uncertainty tests his pride and patience. In Syria, he could buy his children whatever they desired: clothes, computers, karate lessons. Now they’re surviving only by the kindness of strangers.

One night, he winds up in the emergency room with a crippling headache. The pain could be because of stress, he acknowledges, but he says the reading glasses he bought at the Dollar Store are more likely to blame.

The family marks its first month in the U.S. without finding a permanent home. After some pleading, the resettlement agency agrees to pay for them to stay another month at the American Inn. They are starting to resemble the other long-term residents at the $65-a-night motel, the ones with posters hung on their walls and trinkets displayed on their windowsills.

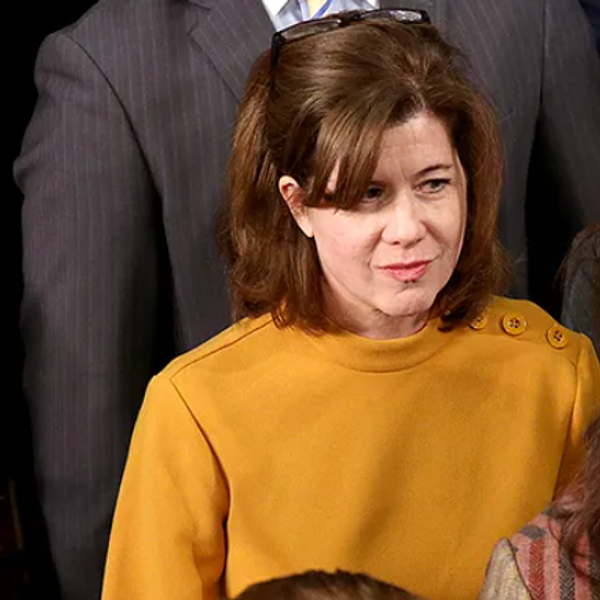

And then, one day, some good news arrives. It’s an invitation from Mountain View Elementary School, where 9-year-old Maram and 12-year-old Omran are enrolled. Can the family attend an upcoming assembly?

Fouad and his wife take their seats in the school’s crowded lunchroom along with Omar, Fara and Massa. There is excitement in the air as the principal reads the names of several youngsters being honored with “courage awards,” given to those who have demonstrated bravery.

Maram’s name is called. So is Omran’s. The Wawieh family erupts in whistles.

A couple of weeks later, Fouad signs his name to a rental contract and accepts keys to a freshly painted three-bedroom apartment in Pomona a few blocks from the motel. He celebrates with a cigarette — he smokes Marlboros now.

He and his family roam room to room inspecting their new home, trying out lights and bathroom faucets and the garbage disposal.

Outside, a truck packed with donated furniture waits to be unloaded.

The first thing his wife carries in is a small pot of bright yellow mums.

©2015 Los Angeles Times. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Photo: After receiving an award for courage in her third grade class, Maram Wawieh, 9, looks up at Mountain View Elementary school principal Natalie Taylor, left, during a school assembly on Oct. 26, 2015 in Claremont, Calif. Her brother, Omran, 12, (not pictured) also received the award for his 6th grade class. (Katie Falkenberg/Los Angeles Times/TNS)