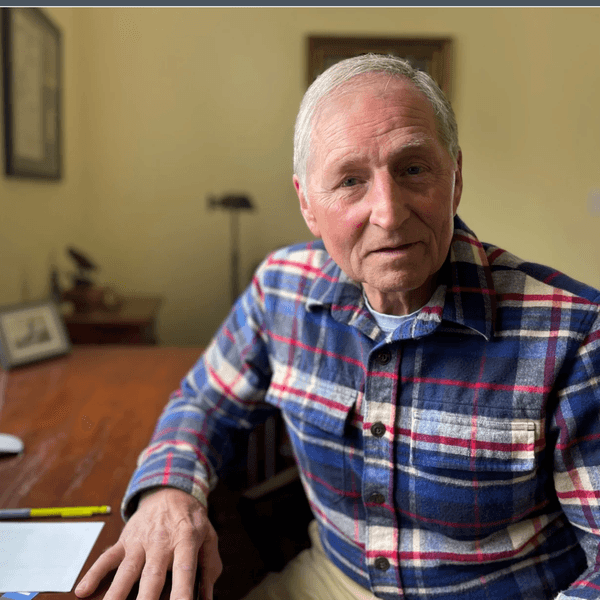

It remains a mystery why the CEO of Federal Government Experts LLC let me observe his frantic effort to find 6 million N95 respirators and the ultimate unraveling of his $34.5 million deal to supply them to the Department of Veterans Affairs hospitals, where 20 VA staff have died of COVID-19 while the agency waits for masks.

It's also unclear why the VA gave Stewart's fledgling business — which had no experience selling medical equipment, no supply chain expertise and very little credit — an important contract. Or why the VA agreed to pay nearly $5.75 per mask, a 350 percent markup from the manufacturer's list price. In the end, after ProPublica asked questions about the deal this week, the VA quickly terminated it and referred the case to its inspector general for investigation.

Stewart maintained he was trying to do a public service and plans to tell investigators how he was taken for a ride by “buccaneers and pirates," the multiple layers of intermediaries, fixers and lawyers standing between respirator mask producers and front-line workers who are dying without them.

I had first contacted Stewart last Friday after a ProPublica analysis of federal contracting data showed this sizable deal was his company's first — and had been awarded without the usual bidding meant to weed out companies that can't deliver.

Stewart wasn't alone. The coronavirus pandemic had unleashed a bonanza for untested contractors riding a wave of unprecedented demand and scarcity of everything from hand sanitizer to ICU beds. So far, the administration of President Donald Trump has handed out at least $5.1 billion in no-bid contracts to address the pandemic, federal purchasing data shows. The VA, far more than any other agency, appeared to be awarding large contracts to little-known vendors in search of the personal protective equipment that's pitted local, state and federal agencies against one another.

I wanted to know how a company the 34-year-old Stewart had formed two years earlier had gotten one of the largest no-bid contracts. And, more importantly, could it fulfill it?

There was reason to wonder. A quick Google search showed large portions of the text on FGE's company website had been lifted verbatim from a 1982 Harvard Business Review article. The company primarily advertised IT consulting and advertised a “block chain" A.I. solution to government procurement, whatever that means. But I found nothing suggesting the company could buy and ship life-saving medical equipment — and fast.

In a phone call, Stewart was defensive about an article on federal contracts in The Wall Street Journal that he believed unfairly painted him as a crook. His mother was so upset she wrote a letter to the editor. “My mom and dad raised me to be a man of integrity," he said.

That's when the first inconsistency arose. The Journal quoted Stewart as saying he was at the Port of Los Angeles “looking at a few million masks" and “getting ready to step on a Boeing 737 to bring the masks to the VA."

He told me, however, that he had been in self-quarantine and hadn't traveled anywhere since Christmas.

But he said he did have 6 million N95 respirators masks lined up in Los Angeles and would be getting a “proof of life video," in the form of cellphone footage of scores of boxes with 3M labels, sent from an unidentified sender. The next day, he planned to take a private plane to the VA distribution center outside of Chicago to witness the delivery. I asked to tag along.

So here we were, aboard a whirring Legacy 450 Flexjet replete with leather captains' chairs, dozens of liquor shooters, snacks and two pilots curious as to why we were stopping in Columbus, Georgia, en route to Chicago. It was a pit stop to pick up Stewart's parents to bring them along for what was supposed to be a proud moment.

“This is about helping folks, about being able to say to my mom and dad, 'Thank you,'" he said. “All the work you did, now we are about to help 6 million people — well, 6 million masks."

“Kind of a Faith Thing"

For a man who said he had spent weeks of sleepless nights in search of masks and learning shipping logistics, Stewart exuded the confidence of a magician about to perform his career-defining trick. But his next act was already falling apart.

We were midair when Stewart revealed that the 6 million masks that were supposedly in LA had slipped from his grasp and been sold to another buyer when he didn't produce the money fast enough. So, he had no masks.

This was the second time Stewart said he had lost a mask supply before he could get his hands on it. He had tried earlier in April to procure masks from China, but that failed when the Chinese government took control of its mask-producing companies and limited exports.

I asked why on earth we were flying to Chicago to try to meet the VA's midnight delivery deadline if he didn't already have the N95s.

“It was kind of a faith thing," he said.

For 24 hours, Stewart had frantically reached out to contacts he had made as a former contract officer for the Pentagon. And early Friday, just one day before his shipment was due to the VA, Stewart said he got connected to a fixer in the U.S.

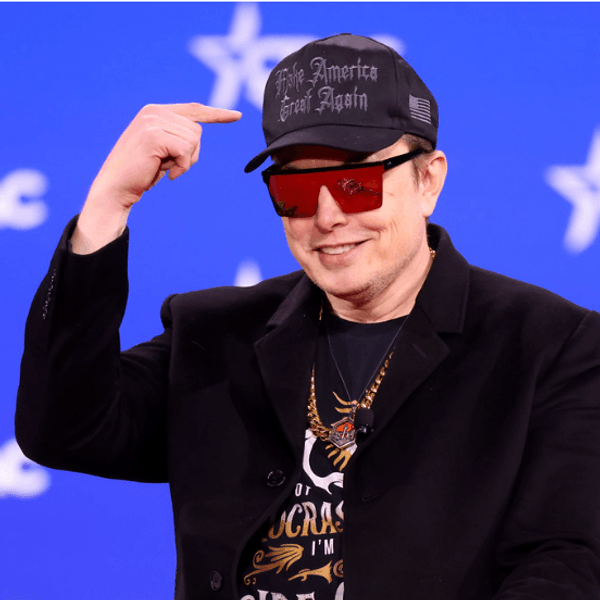

The fixer was Troy King, a former attorney general of Alabama who had just lost a run for Congress in that state's 2nd District. Stewart said King connected him to an unidentified distributor, who could then connect him with 3M, the manufacturer of N95s, which block 95 percent of small particles such as those carrying COVID-19. Stewart said King also promised to arrange financing so FGE could get the deal done fast.

“When you're a poor kid from Alabama," Stewart said, “you do what you need to do to get the job done."

Much of what Stewart told me either proved false or impossible to confirm, which he says is because he was being lied to by brokers and middlemen. For instance, he claimed to have a contact within the White House Coronavirus Task Force, led by Vice President Mike Pence, who was working to help him smooth the deal over with VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. But when I asked spokespeople with the task force and the VA about the name he cited, no one had ever heard of her or had employment records for someone by that name.

Stewart said King was the one who claimed to have Pence task force connections and was brokering the deal through an Alabama LLC, Bear Mountain Development Company. King would charge a broker's fee for connecting FGE to the distributor, Stewart said, and the payout would depend on shipment volume. But the price per mask kept changing. King told Stewart it would cost him $4.90 per mask — without shipping or overhead — to get the supplies from the distributor, according to text messages Stewart shared.

King did not respond to my calls or emails, but through a spokeswoman said he talked to Stewart because he was having trouble getting masks.

“I worked all weekend to locate 3M masks that were available. The only 3M masks we could source for him were priced at $4.90 per mask, which is the price that we were being charged by our supplier."

King said no cash changed hands and that he thought he might forgo the broker fee.

“Due to the fact that these products were for use in veterans' facilities, we agreed that our efforts might end up being an uncompensated public service," the statement said.

The deal's tenuous nature — a broker Stewart didn't know, buying from a seller he didn't know, financed by someone he didn't know — seemed a profound and expensive leap of faith. But Stewart was convinced that he was “getting the VA a good thing at a good price."

He had been called to action, he said, after seeing a CNN segment where a nurse described making her own face shield out of plastic film. As a former Air Force officer, he said he felt compelled to help.

“The goal here is not to get rich," he said. FGE would be lucky to pocket about 10 cents a mask, he said, somewhere around $600,000, when the VA got its goods.

Yet we were bobbing around on a lavish jet, when commercial flights were available at about one one-hundredth of the cost per ticket.

When I asked why he spent more than $22,000 on a private plane, he said it was to prove he was no fly-by-nighter but a reputable government contractor.

“It comes down to me and my credibility," he said. “Why would anybody pay $22,000 to have a ghost box delivery? It doesn't make any sense."

This was money out of FGE's pocket. The government typically doesn't pay vendors like Stewart until the goods are delivered. (ProPublica reimbursed FGE for the cost of a commercial ticket.)

Stewart pulled a faded Bible from his bag and talked about miracles. His chance to prove himself on this deal, he said, is a small miracle.

“Awarding a $34.5 million contract to a small company without any supply chain experience," he mused. “Why would you do that?"

Price Gouging?

Why the VA would do that is a lingering question. While the Federal Emergency Management Agency is officially leading the effort to scrounge up PPE, reportedly plucking shipments out from under states and other parts of the executive branch, the VA made its own supply purchases in March and April.

But despite signing 1,100 contracts worth $591 million just for PPE, the VA has experienced a devastating shortage for weeks. Nurses and doctors are reusing masks, avoiding patients and rationing gear. As BuzzFeed News reported April 7, despite the VA's public assurances that the supply chain was “kicked into full gear," leaders at one hospital said nurses and doctors were allowed only one surgical mask per shift. The more effective N95 masks, which the VA hired Stewart and his company to hunt down three days later, were in such short supply that they could only be used if there was a high chance of aerosolization, meaning the virus was believed to be temporarily airborne.

Though Stewart repeatedly promised to show me his original VA contract pitch, he ultimately declined to share it. What is clear is that FGE, which is designated as a Service-Disabled Veteran-Owned Small Business, had a competitive advantage in securing work at the VA, which sets aside certain contracts for small veteran-owned companies. Stewart declined to talk about how he qualifies as disabled.

Stewart said his deal's cost was being driven up by high demand and by the brokers trying to collect “success fees." While he said King never disclosed his fees, he showed me another contract with a different broker. That offer, which FGE declined, would have paid 5 cents a mask — about $300,000 — to the broker setting up the deal.

Ken Curley, a retired Army colonel whose company works with local governments and hospitals to order masks outside of this emerging black market, called the FGE deal “absolutely" a case of price gouging. “So you have a $4.90 mask before you put it on a truck?" he said. “It's insanity."

Curley's company, Raymond Associates LLC, drafted a best practices paper for buyers like local hospitals, pointing out that 3M's list price for masks like those Stewart was attempting to purchase was $1.27. After shipping costs and overhead, the end price should realistically be around $2 a mask, he said.

“So anybody that's above that number is gouging," Curley said. “And they know it."

Curley said he's seen numerous offers for respirators, many of which did not really exist, and turned away brokers working through multiple layers of intermediaries. To avoid this, he recommends “a single line" between the distributor and the government agency buying the product, meaning there's only one facilitator.

Sergio Fernández de Córdova, who chairs a media nonprofit in New York, is working with Curley to help government agencies get reputable masks at better prices. Government agencies are partly to blame, he said, because they're desperately handing out big contracts to unknown companies and paying exorbitant prices for whatever comes back. In the FGE deal, for instance, the VA essentially set its high price when it agreed to 6 million units at $34.5 million.

“They're approving it," he said. “So that's why people don't see a problem with it."

Though several states have clear price gouging laws, those rules don't apply to federal government purchases.

“It is the Wild West and a loophole — that's why so many lawyers are involved," Fernández de Córdova said. “We've seen deals with lawyers making a couple hundred grand."

3M has filed lawsuits in at least five states against people selling its respirators and masks at obscene markups. The Justice Department is also hunting down alleged scammers, such as two California men who were arrested for selling Chinese versions of the N95 respirators, KN95s, which they didn't actually possess.

Stewart had read about those cases and had been given a copy of Curley's best practices memo, and it clearly worried him.

“I'm just trying to fulfill my obligation and not go to jail," he said.

Empty Hotel, Empty Promises

At 11 a.m. Saturday, Flight N407FX skidded onto warm asphalt in Columbus.

Stewart's mother and father were waiting with luggage, while a few other family members came by to take pictures.

Also joining us was Dawn Lockhart, Stewart's friend from middle school whom he had hired as FGE's human resources director. She, like me, had been told by Stewart that everyone on board would have access to an N95 mask for protection on the flight. But there were none.

Despite his company's moniker, there seemed nothing expert about this operation. Stewart said his company lawyer had missed the flight because he slept in. Lockhart, who joked that she was wearing a skirt and heels for the first time in three years, was flipping through a textbook titled “Strategic Staffing."

Stewart was building his company, like this deal, in midflight.

Once we were airborne, Stewart said he had found a new mask supplier in Atlanta who could quickly deliver to Chicago.

He said that once we landed he would drop his folks off at the Hilton Oak Brook Hills Resort just outside of Chicago and then he and I would take a taxi over to the VA distribution center and wait for a mask delivery “even if we have to wait until 3 a.m."

But we never left the confines of the vast and vacant Hilton, where two employees sat bored behind makeshift plexiglass barriers.

In the lobby, Stewart worked the phones. He needed the VA to sign off on his new arrangement, but to win approval, he needed invoices and other documentation that he said King wasn't sending over.

Just before 2 p.m., King had sent the “proof of life" video that Stewart said he'd been asking for, according to text messages Stewart later shared. The grainy cellphone video pans over what appear to be hundreds of boxes labeled 3M, but it was unclear what was in the boxes or where they were.

By 3 p.m. Stewart had been joined by several friends and associates, including Roosevelt “Trey" Daniels of Frontline Recovery, a Houston disaster recovery firm. Daniels connected FGE to King.

Stewart and Daniels made dozens of calls — to King, to trucking companies, to cargo jet owners. “Hey, Frank," Daniels said into his cell. “Who is a good freight company?" And that would lead to the next call and the next.

By 5:20, Daniels had suggested they send a portion of the shipment by truck to Illinois, while they figured out how to get the rest on planes. Stewart insisted that he wanted to get the whole shipment there at once.

Then, a new idea emerged. Maybe they could buy some time by getting the VA to agree to an extension. Daniels had worked as a district director for U.S. Rep. Sheila Jackson Lee, a Texas Democrat, and got her office to draft a letter in support of FGE.

“Can you lend your voice to this veteran-owned, African American business?" Roosevelt said he asked the congresswoman. “And she said yes. She's always willing to go to bat for folks who are trying to do the right thing."

Stewart drafted a formal extension request, citing provisions in federal contracting law. As the evening wore on, what was at first frenetic determination to pull off a miracle subsided into resignation and then into finger-pointing — at King, the VA bureaucracy, the market itself.

Daniels says the deal went south because King and Stewart faced a challenging market, trying to move cash too fast, while the federal government doesn't provide enough guidance for vendors.

“This situation with Troy King and Rob Stewart is you really have two good guys who had a lot of miscommunications," he said. “One wasn't communicating enough. One had his back against the wall."

“Robert Stewart is a good guy," Daniels said. “He's a very honest guy."

The group ordered tacos for what Stewart said was the company's “last supper." “I've done everything I can do," Stewart said. “I called in every favor I had."

A Federal Investigation

The next morning, as the dejected party boarded for a return flight, the pilot asked: “Anything I can get you before we take off?"

“Six million N95 masks," Stewart quipped.

We landed in Georgia an hour and a half later, Stewart snapped photos with his family in front of the jet, and the two of us took off for Dulles.

The CEO was in the same gray suit as the previous day, now wrinkled. With his friends and family gone, his joviality had given way to exhaustion and the realization that this article probably wasn't going to be one he liked. The optics of the private jet, he said, would not be good.

“The only reason I took the plane was because of my parents," he said. “They're old and I didn't want them to get sick, and I wanted them to see this. I wanted to say thank you."

Stewart said he had severed ties with King the previous night. Stewart said he and his team couldn't track down any Juanita Ramos, the connection King purported to have to Pence's task force. And King hadn't sent over the invoice he needed for the VA.

“I absolutely do believe he made her up," Stewart said Wednesday. King did not respond to a question about Ramos.

“He's the one that made up this figment Ramos lady," Stewart added. “I didn't make that up."

“After several conversations over the weekend, Mr. Stewart informed us that he had secured these masks through another source and that he would not need our services to secure the masks," King said through a spokesperson. “There have been no further conversations between Mr. Stewart and me. No agreement was ever made, no contract was ever executed, and no money was ever exchanged."

Stewart believes there were never any masks in LA or Atlanta.

“Every time you get ready to do the due diligence or whatever else — you ask to see the proof of life — people go: 'Oh, well we don't have that. We have this kind. Or we can't do that until this week or this date.' Stuff just never materializes. It's a bunch of smoke and mirrors and ghosts."

Stewart, to the end, maintained he would find a way to get masks to the VA. He followed up with the VA, offering a contract to get on a production line directly from 3M, at a cheaper cost, just $3.77 a mask.

But the VA terminated the deal Wednesday, after I inquired with the agency and a spokesperson for Pence's task force. The agency didn't tell Stewart directly, though he said he was made aware of the IG investigation.

“The story is that we started out trying to do the best thing for the country," Stewart said. “I failed in that, ultimately."

Back in DC, I asked a VA spokesperson why any of this, the FGE contract and intermediaries, was even necessary. Couldn't the VA just buy masks directly?

The agency is waiting, along with much of the federal government, on FEMA, said spokeswoman Christina Noel. More than 166 million respirators are being produced by 3M under the Defense Production Act over the next few months, “some of which are being provided to the VA."

In the meantime, the VA was hiring contractors to scour for additional masks.

“To meet the remainder of its N95 respirator needs, VA conducts additional acquisition activities with other vendors," Noel said.

In the end, the VA ended up with precisely zero additional N95 masks from its deal with Stewart.

On the up side, the VA paid no money to FGE, Noel said.

As of Wednesday, more than 2,200 VA employees had tested positive for COVID-19.

Do you have access to information about federal contracts that should be public? Email david.mcswane@propublica.org. Here's how to send tips and documents to ProPublica securely.

Derek Willis and Lydia DePillis contributed reporting.