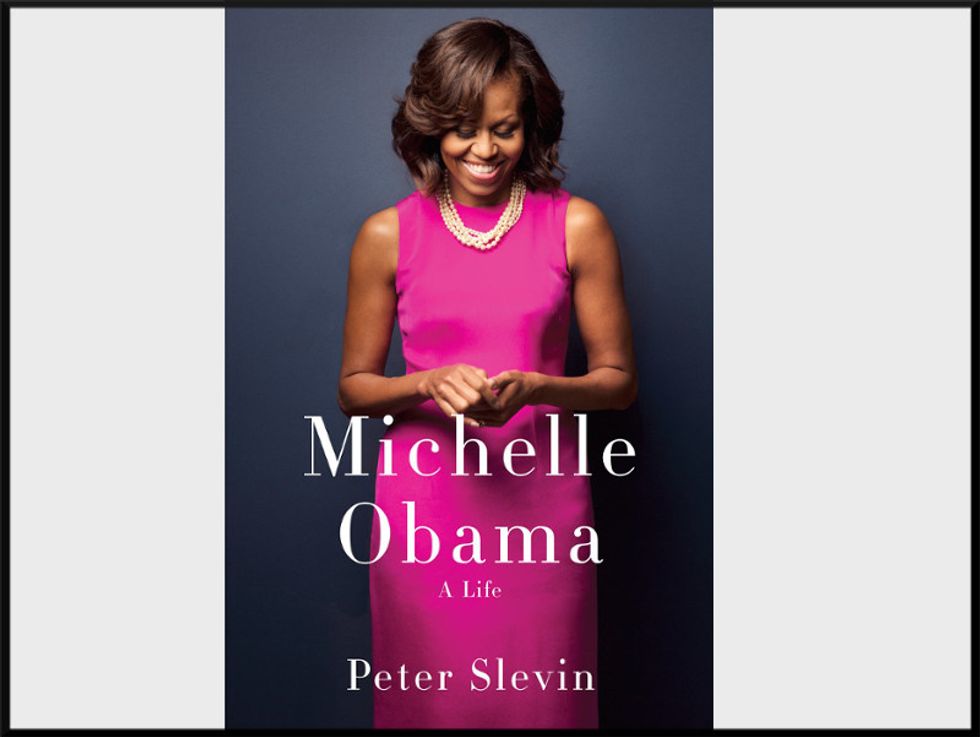

Weekend Reader: ‘Michelle Obama: A Life’

First Lady Michelle Obama once said, “We live in a nation where I am not supposed to be here.” And yet she is a resilient model for many of the things America has aspired to. She’s emblematic of how hard work, intelligence, and audacity can blaze a trail to success. At the same time, as an African-American and a woman, her achievements belie how much entrenched discrimination and racism she must have overcome as well.

Biographer Peter Slevin’s Michelle Obama: A Life is not so much about the power of the First Lady — though the book spends a good amount of time describing its subject’s efficacy in that role — as it is the narrative of the woman who became Michelle Obama. And as Slevin continually reminds readers, her story is also a story of race, identity, and politics in America. “So much had changed in seven decades,” he writes, “and yet much had not.”

You can read Slevin’s introduction below. The book is available for purchase here.

In June 2010, when Michelle Obama cast her eyes across the class of graduating high school seniors from one of Washington’s most troubled black neighborhoods, she saw not only their lives, but her own. The setting was Constitution Hall, where the Daughters of the American Revolution had prevented opera singer Marian Anderson from performing in 1939 because she was black. So much had changed in seven decades, and yet much had not. Michelle spoke to the graduates about the troubles facing African American children in Anacostia, and she spoke about racism. She pointed out that the neighborhood within sight of the U.S. Capitol once was segregated and that black people had been prohibited from owning property in parts of the community. “And even after those barriers were torn down,” she said, “others emerged. Poverty. Violence. Inequality.”

Michelle drew a straight line from her struggles with hardship and self-doubt in working-class Chicago to the fractured world the Anacostia students inhabited thirty years later. She told them about being written off, about feeling rejected, about the resilience it takes for a black kid in a public school to become one of the first in her family to go to college. “Kids teasing me when I studied hard. Teachers telling me not to reach too high because my test scores weren’t good enough. Folks making it clear with what they said or didn’t say that success wasn’t meant for a little girl like me from the South Side of Chicago.” As she spoke of her parents—their sacrifices and the way they pushed her “to reach for a life they never knew” — her voice broke and tears came to her eyes. As the students applauded in support, Michelle went on, “And if Barack were here, he’d say the same thing was true for him. He’d tell you it was hard at times growing up without a father. He’d tell you that his family didn’t have a lot of money. He’d tell you he made plenty of mistakes and wasn’t always the best student.”

She knew that many of the Anacostia students faced disruptions and distractions that sometimes made it hard to show up, much less succeed. It might be family turmoil or money troubles or needy relatives or children of their own. Or maybe the lack of a mentor, a quiet place to study, a lucky break. “Maybe you feel like no one has your back, like you’ve been let down by people so many times that you’ve stopped believing in yourself. Maybe you feel like your destiny was written the day you were born and you ought to just rein in your hopes and scale back your dreams. But if any of you are thinking that way, I’m here to tell you: Stop it.”

There were no cheap lines in Michelle’s speech that day, seventeen months after she arrived in the White House as the unlikeliest first lady in modern history. In a voice entirely her own, she reached deep into a lifetime of thinking about race, politics, and power to deliver a message about inequity and perseverance, challenge and uplift. These were the themes and experiences that animated her and set her apart. No one who looked like Michelle Obama had ever occupied the White House. No one who acted quite like her, either. She ran obstacle courses, she danced the Dougie, she hula-hooped on the White House lawn. She opened the executive mansion to fresh faces and voices and took her show on the road. She did sitcoms and talk shows and participated in cyber showcases and social media almost as soon as they were invented. Cameras and microphones tracked her every move. Maddening though the attention could be, she tried to make it useful. Amid a characteristic media fuss about a new hairstyle, she said of first ladies, “We take our bangs and we stand in front of important things that the world needs to see. And eventually, people stop looking at the bangs and they start looking at what we’re standing in front of.”

Michelle’s projects and messages reflected a hard-won determination to help the working class and the disadvantaged, to unstack the deck. She was more urban and more mindful of inequality than any first lady since Eleanor Roosevelt. She was also more steadily, if subtly, political. Not political in ways measured by elections or ephemeral Beltway chatter, although she made clear her convictions from many a campaign stage. Rather, political as defined by spoken beliefs about how the world should work and purposeful projects calculated to bend the curve. Her efforts unfolded in realms that had barely existed for African Americans a generation earlier, a fact that informed and complicated her work. “We live in a nation where I am not supposed to be here,” she once said.

Michelle’s prospects as first lady delighted her supporters and helped get Barack elected, but her story and its underpinnings remained unfamiliar to many white Americans in a country where black Americans often felt relegated to a parallel universe. “As we’ve all said in the black community, we don’t see all of who we are in the media. We see snippets of our community and distortions of our community,” Michelle said. “So the world has this perspective that somehow Barack and Michelle Obama are different, that we’re unique. And we’re not. You just haven’t seen us before.” She belonged to a generation that came of age after the civil rights movement. It was fashionable in some circles for people to declare that they no longer saw race, but translation would be required. As her friend Verna Williams put it, “So many people have no idea about what black people are like. They feel they know us when they really don’t.” Lambasted early as “Mrs. Grievance” and “Barack’s Bitter Half,” Michelle knew the burden of making herself understood. One of her favorite descriptions of her Washington life came from a California college student who described the role of first lady as “the balance between politics and sanity.”

During her years in the spotlight, Michelle became a point of reference and contention. She built and nurtured her popularity and emerged as one of the most recognizable women in the world. “You do not want to underestimate her, ever,” said Trooper Sanders, a White House aide. Indeed, Michelle seemed to stride through life, full of confidence and direction. Comfortable in her own skin, friends always said. Authentic. But when asked what she would say to her younger self, as an interviewer flashed her high school yearbook photo onto a giant screen, Michelle paused to consider. “I think that girl was always afraid. I was thinking ‘Maybe I’m not smart enough. Maybe I’m not bright enough. Maybe there are kids that are working harder than me.’ I was always worrying about disappointing someone or failing.”

At Constitution Hall, addressing 158 Anacostia seniors dressed in cobalt blue gowns, Michelle shared her history and her self-doubt. She offered advice and encouragement but skipped the saccharine. “You can’t just sit around,” she instructed. “Don’t expect anybody to come and hand you anything. It doesn’t work that way.” She asked them to think about the obstacles faced by Frederick Douglass, their neighborhood’s most illustrious former resident, born into slavery and self-educated in an era when it was illegal to teach slaves to read or write. His mother died when he was a boy and he never knew his father. But he made it, “persevering through thick and thin,” and spent decades fighting for equality. She also asked them to consider the current occupants of the White House. “We see ourselves in each and every one of you. We are living proof for you, that with the right support, it doesn’t matter what circumstances you were born into or how much money you have or what color your skin is. If you are committed to doing what it takes, anything is possible. It’s up to you.”

Excerpted fromMichelle Obama: A Life, by Peter Slevin. Copyright © 2015 by Peter Slevin. Excerpted by permission of Knopf, a division of Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, purchase the full book here.

Want more updates on great books? Sign up for our email newsletter!