How Trump’s Criminality Harkens Back To The Violence Of The Confederacy

Reprinted with permission from Daily Kos

Donald Trump broke new ground as the first president—the first American, period—to be impeached twice. However, thinking of him solely in those terms fails by a long shot to capture how truly historic his crimes were. Forget the number of impeachments—and certainly don't be distracted by pathetic, partisan scoundrels voting to acquit—The Man Who Lost The Popular Vote (Twice) is the only president to incite a violent insurrection aimed at overthrowing our democracy—and get away with it.

But reading those words doesn't fully and accurately describe the vile nature of what Trump wrought on Jan. 6. In this case, to paraphrase the woman who should've been the 45th president, it takes a video.

Although it's difficult, I encourage anyone who hasn't yet done so to watch the compilation of footage the House managers presented on the first day of the impeachment trial. It left me shaking with rage. Those thugs wanted not just to defile a building, but to defile our Constitution. They sought to overturn an election in which many hadn't even botheredthemselves to vote.

What was their purpose? In their own words, as they screamed while storming the Capitol: "Fight for Trump! Fight for Trump!" Those were the exact same words they had chanted shortly beforehand during the speech their leader gave at the Ellipse. He told them to fight for him, and they told him they would. And then they did.

Many of those fighting for Trump were motivated by a white Christian nationalist ideology of hate—hatred of liberals, Jews, African Americans, and other people of color. Most of that Trumpist mob standsdiametrically opposed to the ideals that really do make America great—particularly the simple notion laid down in the Declaration of Independence that, after nearly 250 years, we've still yet to fully realize: All of us are created equal. The Jan. 6 attack on the Capitol was but another battle in our country's long-running race war.

As Rev. William Barber explained just a few days ago: "White supremacy, though it may be targeted at Black people, is ultimately against democracy itself." He added: "This kind of mob violence, in reaction to Black, brown, and white people coming together and voting to move the nation forward in progressive ways, has always been the backlash."

Barber is right on all counts. White supremacy's centuries-long opposition to true democracy in America is also the through-line that connects what Trump has done since Election Day and on Jan. 6 to his true historical forebears in our history. Not the other impeached presidents, whose crimes—some more serious than others—differed from those of Trump not merely by a matter of degree, but in their very nature. Even Richard Nixon, as dangerous to the rule of law as his actions were, didn't encourage a violent coup. That's how execrable Trump is; Tricky Dick comes out ahead by comparison.

Instead, Trump's true forebears are the violent white supremacists who rejected our democracy to preserve their perverted racial hierarchy: the Southern Confederates. It's no coincidence that on Jan. 6 we saw a good number of Confederate flags unfurled at the Capitol on behalf of the Insurrectionist-in-Chief. As many, including Penn State history professor emeritus William Blair, have noted: "The Confederate flag made it deeper into Washington on Jan. 6, 2021, than it did during the Civil War."

As for that blood-soaked, intra-American conflict—after Abraham Lincoln was elected president in 1860, 11 Southern states refused to accept the results because they feared it would lead to the end of slavery. They seceded from the Union and backed that action with violence. Led by their president, Jefferson Davis, they aimed to achieve through the shedding of blood what they could not at the ballot box: to protect their vision of a white-dominated society in which African Americans were nothing more than property.

Some, of course, will insist the Civil War began for other reasons, like "states' rights," choosing to skip right past the words uttered, just after President Lincoln's inauguration, by Alexander Stephens, who would soon be elected vice president of the Confederacy. Stephens describedthe government created by secessionists thusly: "Its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery—subordination to the superior race—is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth."

In the speech he gave at his 1861 inauguration, Lincoln accurately diagnosed secession as standing in direct opposition to democracy.

Plainly the central idea of secession is the essence of anarchy. A majority held in restraint by constitutional checks and limitations, and always changing easily with deliberate changes of popular opinions and sentiments, is the only true sovereign of a free people. Whoever rejects it does of necessity fly to anarchy or to despotism. Unanimity is impossible. The rule of a minority, as a permanent arrangement, is wholly inadmissible; so that, rejecting the majority principle, anarchy or despotism in some form is all that is left.

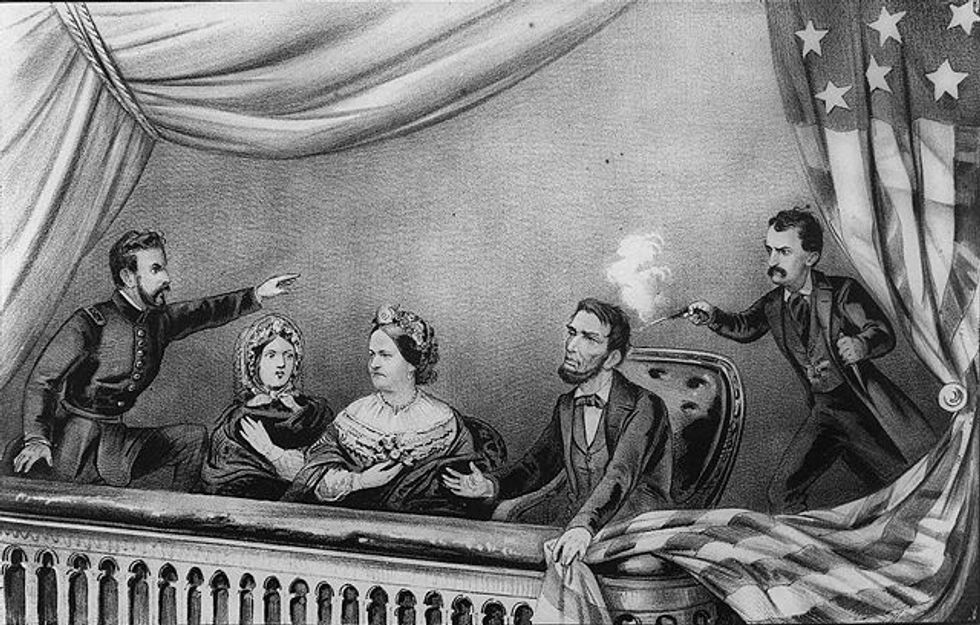

Davis, Stephens, and the rest of the Confederates spent four long years in rebellion against democracy and racial equality. In 1865, Lincoln was sworn in for a second term. On the ballot the previous year had been his vision, laid out at Gettysburg, of a war fought so that our country might become what it had long claimed to be, namely a nation built on the promise of liberty and equality for every American. Lincoln's vision won the election. He planned to lead the Union to final victory and, hopefully, bring that vision to life. Instead, John Wilkes Booth shot the 16th president to death.

Why did Booth commit that violent act, one that sought to remove a democratically elected president? Look at his own written words: "This country was formed for the white, not for the black man. And looking upon African Slavery from the same stand-point held by the noble framers of our constitution. I for one, have ever considered (it) one of the greatest blessings (both for themselves and us,) that God has ever bestowed upon a favored nation."

As author and Washington College historian Adam Goodheart explains, Booth was "motivated by politics and he was especially motivated by racism, by Lincoln's actions to emancipate the slaves and, more immediately, by some of Lincoln's statements that he took as meaning African Americans would get full citizenship." When Booth opened fire, his gun was aimed at not just one man, but at the notion of a multiracial, egalitarian democracy itself.

Trump may not have pulled a trigger, bashed a window, or attacked any police officers while wearing a flag cape, but he shares the same ideology, motive, and mindset as his anti-democratic, white supremacist forebears. They didn't like the result of an election, and were ready and willing to use violence to undo it. Secession, assassination, insurrection. These are three sides of a single triangle.

I hope, for the sake of our country and the world, we never have another president like Donald Trump. I hope we as a people—or at least enough of us—have learned that we cannot elect an unprincipled demagogue as our leader.

A person without principle will never respect, let alone cherish, the Constitution or the democratic process. A person without principle can only see those things as a means to gain or maintain a hold on power. A person without principle believes the end always justifies the means.

That's who Trump is: a person without principle. That's why he lied for two months after Election Day, why he called for his MAGA minions to come to Washington on the day Joe Biden's victory was to be formally certified in Congress, and why he incited an insurrection on that day to prevent that certification from taking place. His forces sought nothing less than the destruction of American democracy.

For those crimes, Trump was impeached, yes. But those crimes are far worse than those committed by any other president. Regardless of the verdict, those crimes will appear in the first sentence of his obituary. They are what he will be remembered for, despite the cowardice of his GOP enablers. Forever.

Ian Reifowitz is the author of The Tribalization of Politics: How Rush Limbaugh's Race-Baiting Rhetoric on the Obama Presidency Paved the Way for Trump (Foreword by Markos Moulitsas)