Reprinted with permission fromAlterNet.

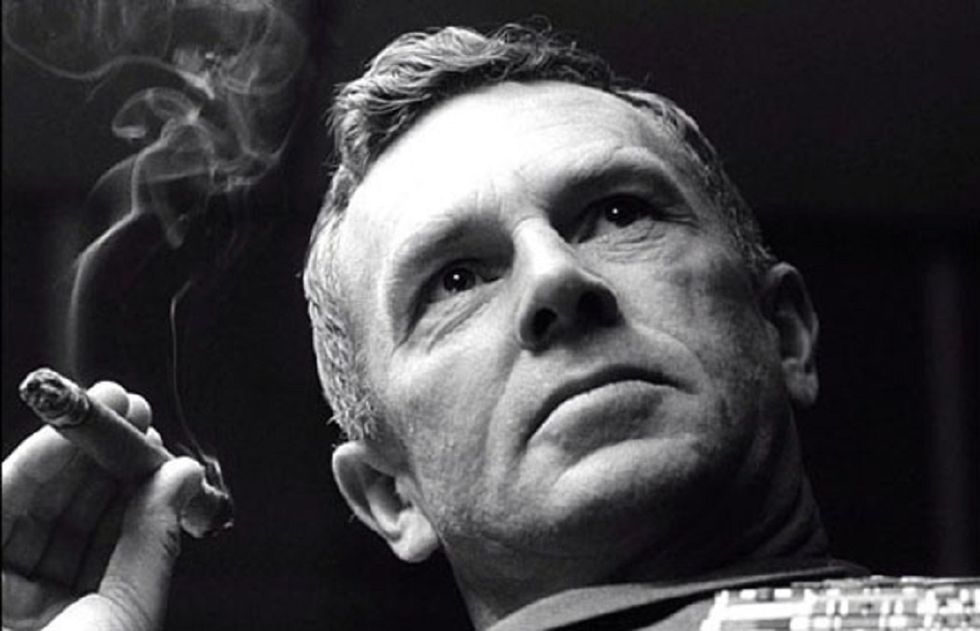

Asked to explain his political views, Theodor Geisel — better known as Dr. Seuss — once said that he was “against people who push other people around.” Were he alive today, he would surely be using his sharp pen to make fun of Donald Trump.

On March 2, tens of millions of children and their parents read Dr. Seuss books as part of Read Across America Day, sponsored by the National Educational Association (NEA) in partnership with local school districts and some businesses. The NEA, which started the program 20 years ago to encourage reading, was smart to tie the program to Dr. Seuss, who remains — 26 years after his death — the world’s most popular writer of modern children’s books.

As kids and as parents, most Americans know all about The Cat in the Hat, How the Grinch Stole Christmas, Green Eggs and Ham, and many others of Seuss’s colorful characters and stories. What some may not know is that despite his popular image as a kindly cartoonist for kids, Geisel was also a political progressive whose views permeate his children’s tales. Many of his books use ridicule, satire, wordplay, nonsense words, and wild drawings to take aim at bullies, hypocrites, and demagogues. Trump would have been an easy target for Geisel’s artistic outrage and moralistic mockery.

His popular children’s books included parables about racism, anti-Semitism, the arms race, corporate greed, and the environment. But, equally important, he used his pen to encourage youngsters to challenge bullies and injustice. Many Dr. Seuss books are about the misuse of power — by despots, kings, and other rulers, including the sometimes arbitrary authority of parents.

In a university lecture in 1947 — a decade before the civil rights movement — Geisel urged would-be writers to avoid the racist stereotypes common in children’s books. America “preaches equality but doesn’t always practice it,” he noted. Generations of progressive activists may not trace their political views to their early exposure to Dr. Seuss, but without doubt this shy, brilliant genius played a role in sensitizing them to abuses of power.

In several early books — including The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins (1938), The King’s Stilts (1939), and Bartholomew and the Oobleck (1949) — Geisel made fun of the pretension, foolishness, and arbitrary power of kings.

In 1941, Geisel became an editorial cartoonist for the left-wing New York City daily newspaper PM. Fervently pro-New Deal, PM included sections devoted to unions, women’s issues, and civil rights. Geisel sharpened his political views as well as his artistry and his gift for humor at PM, where he drew over 400 cartoons.

Before many Americans were aware of the calamity confronting Europe’s Jews, Geisel — a Lutheran who grew up in a tight-knit German American community in Springfield, Massachusetts — drew editorial cartoons for PM that warned readers about Hitler and anti-Semitism, and attacked the “America First” isolationists who turned a blind eye to the rise of fascism and the Holocaust. Trump adopted “America First” as one of his campaign themes.

His PM cartoons viciously but humorously attacked Hitler and Mussolini. He bluntly criticized isolationists who opposed American entry into the war, especially the famed aviator (and Hitler booster) Charles Lindbergh, right-wing radio priest Father Charles Coughlin, and Senator Gerald Nye of North Dakota. Trump has rekindled anti-Semitism, nativism, and isolationism with his bombastic and hateful rhetoric.

Through his PM drawings, Geisel was one of the few editorial voices to decry the U.S. military’s racial segregation policies. He used his cartoons to challenge racism at home against Jews and blacks, union-busting, and corporate greed, which he thought divided the country and hurt the war effort. Geisel would have used his pen to remind his audience about the vicious anti-union campaign that Trump waged at his Trump International Hotel in Las Vegas and his campaign comments about lowering America’s minimum wage in order to compete with China and other foreign countries.

After World War II, Geisel occasionally submitted cartoons to publications, such as a 1947 drawing, published in the New Republic, depicting Uncle Sam looking in horror at Americans accusing each other of being communists and disloyal Americans, a clear statement of Geisel’s anger at the nation’s right-wing Red Scare hysteria, which soon spiraled into McCarthyism. Geisel would surely have dipped into his inkwell to lambast Trump’s outrageous “birther” accusations questioning President Obama’s loyalty and American citizenship, which fueled Trump’s campaign for president.

Geisel devoted almost his entire post-war career to writing children’s books and quickly became a well-known and commercially successful author — thanks in part to the post-war baby boom. He was popular with parents, kids, and critics alike.

His 1954 book, Horton Hears a Who!, was written during the McCarthy era. It features Horton the Elephant, who befriends tiny creatures (the “Whos”) whom he can’t see, but whom he can hear, thanks to his large ears. Horton rallies his neighbors to protect the endangered Who community. Horton agrees to protect the Whos, observing, in one of Geisel’s most famous lines, “even though you can’t see or hear them at all, a person’s a person, no matter how small.” The other animals ridicule Horton for believing in something that they can’t see or hear, but he remains loyal to the Whos. Horton urges the Whos to join together to make a big enough sound so that the jungle animals can hear them. That can happen, however, only if Jo-Jo, the “smallest of all” the Whos, speaks out. He has a responsibility to add his voice to save the entire community. Eventually he does so, and the Whos survive.

The book is a parable about protecting the rights of minorities, urging “big” people to resist bigotry and indifference toward “small” people, and the importance of individuals (particularly “small” ones) speaking out against injustice. A reviewer for the Des Moines Register hailed it as a “rhymed lesson in protection of minorities and their rights.” It isn’t difficult to imagine that Geisel would have a lot to say, and draw, about Trump’s track record of discriminating against African Americans in his apartment buildings — a practice that led to a lawsuit filed against Trump by the U.S. Department of Justice for violating the federal Fair Housing Act — or his ongoing attacks on immigrants and Muslims.

Geisel’s finest rendition of his progressive views is found in Yertle the Turtle (1958). Yertle, king of the pond, stands atop his subjects in order to reach higher than the moon, indifferent to the suffering of those beneath him. In order to be “ruler of all that I see,” Yertle stacks up his subjects so he can reach higher and higher. Mack, the turtle at the very bottom of the pile, says:

Your Majesty, please / I don’t like to complain

But down here below / We are feeling great pain

I know up on top / You are seeing great sights

But down at the bottom / We, too, should have rights.

Yertle just tells Mack to shut up. Frustrated and angry, Mack burps, shaking the carefully piled turtles, and Yertle falls into the mud. His rule ends and the turtles celebrate their freedom.

The story is clearly about Hitler’s thirst for power. But Geisel is also saying that ordinary people can overthrow unjust rulers if they understand their own power. The story’s final line reflects Geisel’s democratic and anti-authoritarian political outlook:

And turtles, of course … all the turtles are free

As turtles, and maybe, all creatures should be.

Geisel would no doubt make fun of Trump’s lust for fame and power and his climb to the top of his real estate empire on the backs of his employees — waiters, dishwashers, and plumbers, among others — and contractors whom he stiffed by failing to pay them for services they rendered. Geisel would also find much to criticize regarding Trump’s authoritarian tendencies and his outrageous megalomania.

The Sneetches (1961), inspired by the Protestant Geisel’s opposition to anti-Semitism, exposes the absurdity of racial and religious bigotry. Sneetches are yellow bird-like creatures. Some Sneetches have a green star on their belly. They are the “in” crowd and they look down on Sneetches who lack a green star, who are the outcasts. One day a “fix-it-up” chap named McBean appears with some strange machines. He offers the star-less Sneetches an opportunity to get a star by going through his “star on” machine, for three dollars each. This angers the star-bellied Sneetches, who no longer have a way to display their superiority. But McBean tells them that for ten dollars, they can use his “star off” machine, ridding themselves of their stars and thus, once again, differentiating themselves from the outcast group.

The competition escalates as McBean persuades each Sneetch group to run from one machine to the other “until neither the Plain nor the Star-Bellies knew / Whether this one was that one or that one was this one / Or which one was what one or what one was who.”

Eventually both groups of Sneetches run out of money. After McBean leaves, all the Sneetches realize that neither the plain-belly nor the star-belly Sneetch is superior. The story is an obvious allegory about racism and discrimination, clearly inspired by the yellow stars that the Nazis required Jews to wear on their clothing to identify them as Jewish.

Were he alive now, Geisel would surely object to the similar ideas emanating from Trump during his campaign — including his anti-Semitic tweet depicting a Jewish star surrounded by dollar bills and his inflammatory rhetoric about Muslims, Mexicans, and people with physical disabilities. Nor is it difficult to imagine that Geisel would have a lot to say, and draw, about Trump’s failure to mention Jews when he issued a proclamation about Holocaust Remembrance Day, and his unwillingness to condemn recent hate crimes targeted at Jewish cemeteries, community centers, and day schools until he was pressured to do so.

Geisel’s The Lorax (1971) appeared as the environmental movement was just emerging, less than a year after the first Earth Day. He later called it “straight propaganda”— a polemic against pollution — but it also contains some of his most creative made-up words, like “cruffulous croak” and “smogulous smoke.”

The book opens with a small boy listening to the Once-ler tell the story of how the area was once full of Truffula trees and Bar-ba-loots and was home to the Lorax. But the greedy Once-ler — clearly a symbol of business — cuts down all the trees to make thneeds, which “everyone, everyone, everyone needs.” The lakes and the air become polluted, there is no food for the animals, and it becomes an unlivable place. The fuzzy yellow Lorax (who speaks for the trees, “for the trees have no tongues”) warns the Once-ler about the devastation he’s causing, but his words are ignored.

The Once-ler cares only about making more things and more money. “Businesss is business! / And business must grow,” he says. At the end, surveying the devastation he has caused, the Once-ler shows some remorse, telling the boy: “Unless someone like you / cares a whole awful lot / nothing is going to get better / It’s not.”

The Lorax is an attack on corporate greed — a trait that Geisel would certainly recognize in Donald Trump, along with his denials of global warming, his pledge to expand the use of coal to generate electricity, his attacks on the Environmental Protection Agency, and his pledge (during his speech to Congress this week) to weaken environmental regulations.

In 1984, Geisel produced The Butter Battle Book, another strong statement about a pending catastrophe, in this case the nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union, fueled by President Reagan’s Cold War rhetoric. “I’m not anti-military,” Geisel told a friend at the time, “I’m just anti-crazy.” It is a parable about the dangers of the political strategy of “mutually assured destruction” brought on by the escalation of nuclear weapons.

In this book, Geisel’s satirical gifts are on full display. The cause of the senseless war is a trivial conflict over toast. The battle is between the Yooks and the Zooks, who don’t realize that they are more alike than different, because they live on opposite sides of a long wall. The Yooks eat their bread with the butter-side up, while the Zooks eat their bread with the butter-side down. They compete to make bigger and better weapons until both sides invent a destructive bomb (the “Bitsy Big-Boy Boomeroo”) that, if used, will kill both sides. Like The Lorax, there is no happy ending or resolution. As the story ends, the generals on both sides of the wall are poised to drop their bombs. It is hard for even the youngest reader to miss Geisel’s point.

Geisel would surely poke fun at Trump’s cavalier and bombastic attitude toward nuclear weapons as well as his proposal, announced at his speech to Congress this week, to increase the Defense Department budget by $54 billion.

Geisel wrote and illustrated 44 children’s books characterized by memorable rhymes, whimsical characters, and exuberant drawings that encouraged generations of children to love reading and expand their vocabularies. His books have been translated into more than fifteen languages and sold over 200 million copies.

His books consistently reveal his sympathy with the weak and the powerless and his fury against bullies and despots. His books teach children to think about how to deal with an unfair world. Rather than instruct them, Geisel invited his young readers to consider what they should do when faced with injustice. Geisel believed children could understand these moral questions, but only rarely did he portray them in overtly political terms. Instead, he wrote, “when we have a moral, we try to tell it sideways.”

Although Trump has been subject to much criticism and satire by columnists, editorial writers, TV pundits, and comedians, as well as Alec Baldwin on Saturday Night Live, no cartoonist has been able to scrutinize and ridicule his bullying and buffoonery the way Geisel dissected the despots and blowhards of his era. We could surely use Geisel’s voice — and his pen — since Trump took office.

Peter Dreier is professor of politics and chair of the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College.

IMAGE: Ron Ellis / Shutterstock.com