Need Clean Water? Take A Page From Researcher’s Book

By Eleanor Chute, Pittsburgh Post-Gazette (TNS)

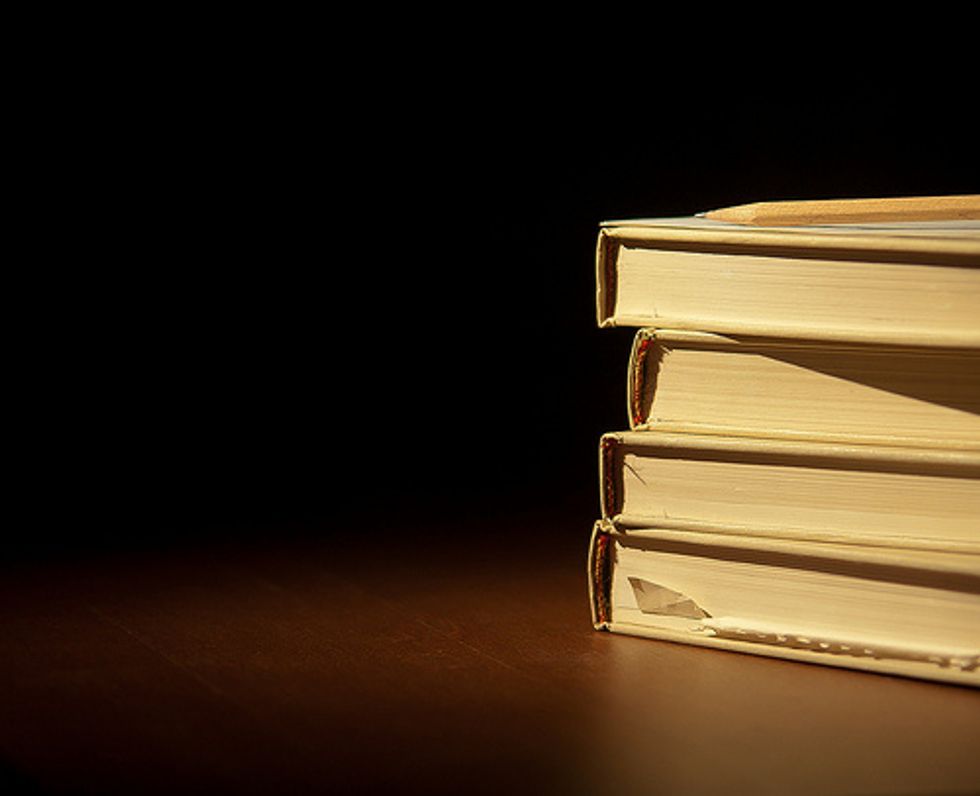

PITTSBURGH — Can bacteria-killing filter paper packaged in the form of a convenient book help people around the globe gain access to clean drinking water?

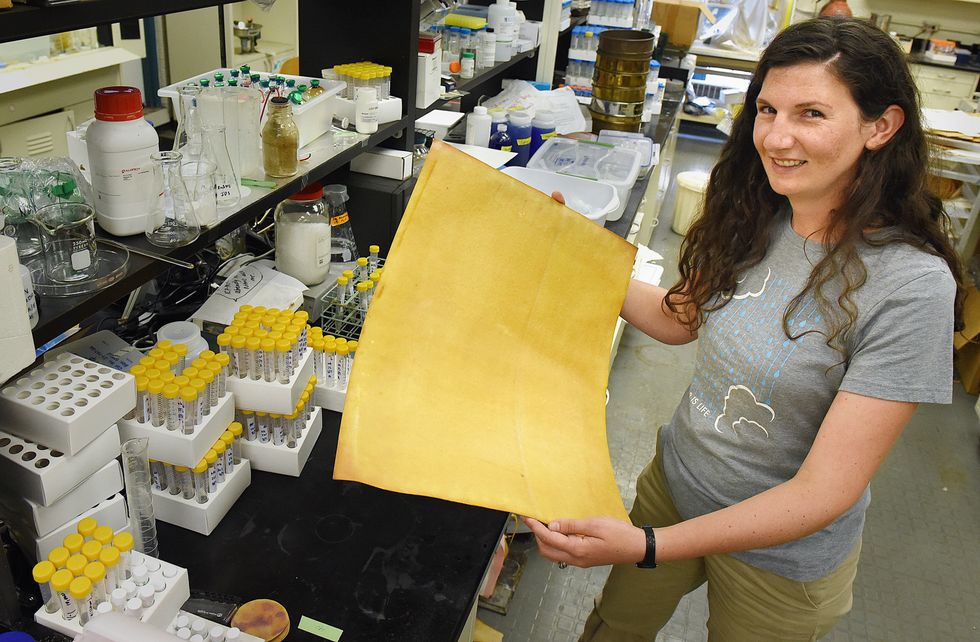

That’s the hope of Theresa Dankovich, postdoctoral research associate in the civil and environmental engineering department of Carnegie Mellon University, who has developed “The Drinkable Book.”

In the works since 2008 while Dankovich was a doctoral student at McGill University in Montreal, the book generated buzz and national and international publicity at the American Chemical Society meeting in Boston last week.

The first page makes the mission clear: “The water in your village may contain deadly diseases but each page of this book is a paper water filter that will make it safe to drink.”

According to the nonprofit water.org, 840,000 people die each year of water-related disease, and one in nine people lack access to safe water. The filter is designed to eliminate water-borne bacteria; it killed 99.9999 percent in lab tests.

In the prototype, each page has two filters, separated by perforations. The top has a message in English; the bottom the same message in the local language. Users can tear off a filter, place it in a holder above a clean container and then pour water into the filter. The optimum holder design for effective and easy use is still being developed by University of Cincinnati design graduate Luke Hydrick, now with Continuum, a design consultancy.

The length of time for water to filter through to the container varies, depending on how much debris is in the water. Each page can filter up to 26 gallons.

Dankovich initially was working on making antibacterial paper, which has many applications such as food packaging and medical masks.

“I just was intrigued by the idea of just a cheap water filter. I wasn’t necessarily thinking of any particular market. I was trying to focus on the science. Then I started to read more about the water crisis. I thought this could be a great method to clean water for a lot of people out there,” she said.

In 2013, she did field testing in Limpopo, South Africa. The following year, she did testing in northern Ghana and this past summer in Bangladesh. People from a nonprofit partner organization, WATERisLIFE, have done testing in Haiti and Kenya.

More than a year ago, Dankovich formed a nonprofit called pAge Drinking Paper. The idea for turning the drinking paper into a book came from a New York designer, Brian Gartside, then at DDB NY and now at Deutsch, after he read about her filter paper work.

With help from CMU students, Dankovich makes her filters by hand. She begins with big sheets of filter paper that are thick — almost like cardboard — and chemically treated so they don’t fall apart when water is poured on then.

She then treats the paper with silver nanoparticles, which turn the paper a shade of orange. The nanoparticles are the key to eliminating bacteria.

A silver salt is applied to the paper, and the paper is baked for 10 or 15 minutes in a commercial oven at a Friendship church. She takes the sheet home, pours distilled water on it to take off excess material, hand blots it to soak up extra water and lets it dry in her basement. Then the papers are sent out for binding and printing using food-grade ink on a letterpress.

Dankovich and her students also are experimenting with copper nanoparticles, which can have a similar anti-bacterial effect. Copper is 100 times cheaper than silver.

She figures about 2,000 pages — each with two filters — have been made so far. Some have been used to make about 50 books. The challenge is finding ways to bring production up to scale. The hope is that ultimately each filter could be manufactured for 10 cents or less.

“Poverty just often reduces people’s ability to buy basic things. Water purification sometimes can be a luxury for people, which sounds horrible, but that’s just how it is,” she said.

The Drinkable Book isn’t ready to go on the market yet. More testing, including trials by users, lies ahead. A campaign on the Internet site Indiegogo seeks $30,000 for pilot scale tests in two villages for about a month. With $150,000, the technology could be tried in about a dozen villages, each for a month or two. Government research grants also are being sought.

“I have gotten a lot of emails requesting books. I wish I could, but we’re not quite there yet,” she said.

Photo: Carnegie Mellon University researcher Theresa Dankovich is developing filter paper treated with silver nanoparticles that can eliminate bacteria when used to filter water. One application is a book made with pages of the filter paper that can be ripped from the book to filter water as needed. (Bob Donaldson/Pittsburgh Post-Gazette/TNS)