Weekend Reader: ‘Save Our Unions: Dispatches From A Movement In Distress’

Today the Weekend Reader brings you Save Our Unions: Dispatches from a Movement in Distress, by labor journalist and union representative Steve Early. Early gives a voice to union workers who are losing funding and collective bargaining rights in the name of big business and elected leaders’ political gains. The decline of unions in the U.S. is a serious issue that has fallen off the radar of mainstream media. A labor revival is vital, but what’s needed first is a fundamental understanding of how the rights of millions are being denied — and that’s precisely what Early offers in Save Our Unions. In this excerpt, the author discusses the home health care industry and the attack on their union rights by politicians across the country.

You can purchase the full book here.

One of the cruel ironies of America’s health care system is how poorly it covers caregivers themselves—particularly those who toil, without professional status, in hospitals, nursing homes, and home health care. More than 2.5 million people now work in this last field. Home health aides (or personal care attendants, as they are sometimes called) are mainly low-income, often non-white, female, and, in some states, foreign-born. Their contingent labor is largely invisible as well as undervalued. Even with union representation, the work pays little more than the minimum wage and lacks significant benefits. Already the second-fastest-growing occupation in the country, home health and personal care jobs are expected to double by 2018.

The good news is that homecare has been an area of explosive union growth in the last two decades, as Eileen Boris and Jennifer Klein report in their new book, Caring for America.’ The bad news is that recent union gains are being rolled back in big states like Wisconsin, Ohio, and Michigan. There, Republican governors have undone the union organizing deals made by their Democratic predecessors that created new bargaining units composed of home health aides and, in some states, child care providers also. As a result, nearly 50,000 newly organized workers have lost their precarious toehold at the bottom rung of public employment.

Prior to the wave of 2010 GOP gubernatorial victories in the Midwest, the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) and at least four other unions had managed to win bargaining rights for more than half a million home-based workers. Previously—and to this day in most places—home health care aides and home day care providers were unfairly classified as “independent contractors.” They had no organizational voice and, in some cases, the “nontraditional workplace” where they cared for children, the aged, or disabled was their own home.

In return for union recognition from union-friendly Democratic governors and legislators, SEIU, the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME), the American Federation of Teachers (AFT), the Communications Workers of America (CWA), and the United Auto Workers (UAW) all agreed that their new home-based worker bargaining units would not be covered by existing state worker medical or retirement plans. In labor’s latest successful campaign, 11,000 Medicaid-paid personal care attendants and state-funded day care workers gained bargaining rights in Connecticut, thanks to new Democratic Governor Dan Malloy. But they, like their counterparts elsewhere, will be negotiating health insurance quite different from the coverage enjoyed by state employees unionized for decades.

In key midwestern states, the right to bargain itself is being lost, along with some fragile first and second contract gains. In Michigan, 40,000 child care workers represented by the UAW and AFSCME won bargaining rights in December 2006 through an executive order. In early 2011, Republican Governor Rick Snyder cut pay by 25 percent and terminated union dues collection for more than 16,000 of these workers. In Ohio, GOP Governor John Kasich similarly rescinded contract coverage for 14,000 recently unionized child care and home care workers. Another group of 4,000 home health care aides in Wisconsin failed to win legislative approval of the $9 per hour minimum wage they negotiated in 2010. Then, as part of Governor Scott Walker’s broader attack on public employee bargaining in the state, he abolished the Quality Home Care Authority created in 2009 to facilitate personal care attendant unionization.

Multiple lawsuits have been filed by right-wing groups opposed to any expansion of public sector bargaining, particularly by executive order. Three legal challenges were mounted in Connecticut to thwart Malloy’s initiative. In Missouri, SEIU and AFSCME engineered a statewide referendum authorizing home care unionism in 2008. But, even after the two unions later won representation votes among 13,000 workers, conservative foes stalled first contract negotiations for nearly four years, until the state supreme court finally upheld SEIU-AFSCME certification. In California, Jerry Brown—a governor elected, like Malloy, with strong labor support—vetoed a bill passed by state legislators that would have allowed thousands of child care providers to unionize more easily, through a card check process. Citing fiscal constraints, Brown balked at extending bargaining rights to the same kind of workforce that is union-represented in New York, New Jersey, Oregon, and now Connecticut.

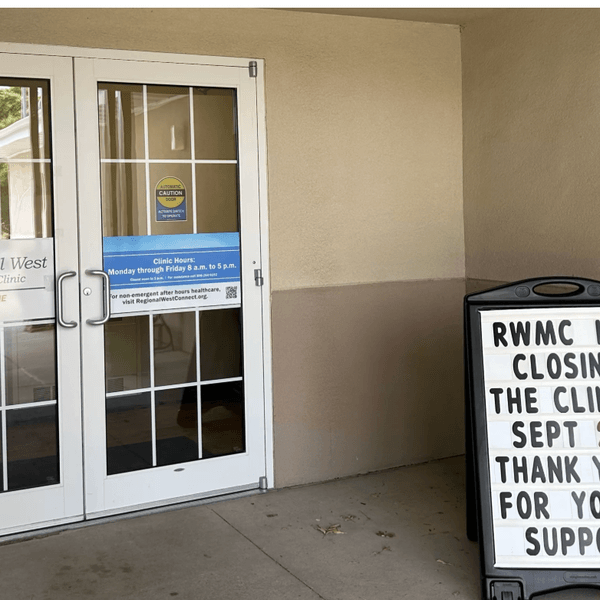

In these states and others run by Democrats, direct care providers will lose their jobs due to budget cuts affecting home-based child care and health services. Since these programs often involve “the poor caring for the poor,” as Boris and Klein note, when funding is reduced, hours cut back, or employment eliminated entirely, low-income Americans suffer as both workers and clients. While not threatening their collective bargaining rights, new Democratic governors are squeezing benefits that affect unionized caregivers. In New York State, Governor Andrew Cuomo’s proposed budget for 2011 slashed more than $2 billion from education and health care spending. New York City-based 1199 SEIU, which represents 70,000 home care workers, remained hopeful that its members will be protected. “Delivering state savings without disruption to Medicaid beneficiaries and their caregivers is an enormous feat,” union president George Gresham told The New York Times.

As 1199 pointed out in late 2010, “State Medicaid funding to the home health services sector has been cut 9 separate times in just the last three years.” As a result, nearly half of the union’s home care members, who often make less than $15,000 a year, lost their coverage under the 1199 health care trust. In addition, to protect the medical benefits of working members who still qualify for health care, thousands of dependent children have been dropped from the union plan because of a reported shortfall between employer contributions and the higher premiums now being charged by its insurance provider. (Most of the children affected are eligible for alternative coverage through New York State’s Children Health Plus program.)

In California, spending reductions announced in 2011 by Brown included nearly $3 billion worth of cuts in Medicaid and welfare-to-work programs. Several hundred thousand unionized caregivers are employed in California’s county-administered but state-funded In-Home Supportive Services program. Many will feel the impact of this budget crunch. In ten other states where home care unionism is a much newer phenomena, similar reductions in jobs, hours, or compensation can be expected. As Caring for America documents, the deepest economic crisis since the Great Depression, public sector budget crises everywhere, and right-wing ascendancy in some state capitals has exposed an “Achilles’ heel of the organizing model established by SEIU and copied by other unions.”

In their book, Eileen Boris, who is chair of the Feminist Studies Department at UC Santa Barbara, and Jennifer Klein, a history professor at Yale, describe the contested terrain of home-based labor, now and in the past. The authors provide valuable historical background on the development of various forms of privately and publicly funded home care work. They also offer a balanced assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of recent union growth in this sector, which has at times been accompanied by considerable inter-union competition and conflict, particularly in California and Illinois. Caring far America includes detailed case studies of successful home care organizing, often aided by experienced community and labor organizers from ACORN. This part of their book is a useful reminder of what that organization helped the working poor accomplish before it was weakened by internal dysfunction, demonized by the right, defunded by its foundation friends, abandoned by labor, and then dismantled as a national entity.

Two-thirds of the 2.5 million workers who provide direct care in clients’ homes are still awaiting action by their supposed friends that would finally give them coverage under the federal Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). As Boris and Klein wrote in Labor Notes during the 2012 presidential race, the U.S. Department of Labor has been dragging its feet on a rule-making initiative to extend FLSA minimum wage and overtime law protections to home health aides. “The home care franchise industry, estimated to be worth $84 billion, has mobilized its defenders against the new rule. The Obama administration, meanwhile, has been thrown off balance by pushback from . . . some disability advocates who fear they will have fewer funds available if their attendants must be paid overtime.” Even with the possibility of the White House changing hands, the Obama administration has yet to finalize this critically important rule change. As Boris and Klein note, “If Mitt Romney wins not only will this initiative be dead in the water but the Republicans in Congress have already introduced bills to permanently classify aides and attendants as ‘companions’ rather than as workers” entitled to normal FLSA coverage.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, purchase the full book here.

From Save Our Unions by Steve Early. Copyright © 2014. Reprinted by permission of Monthly Review Press.

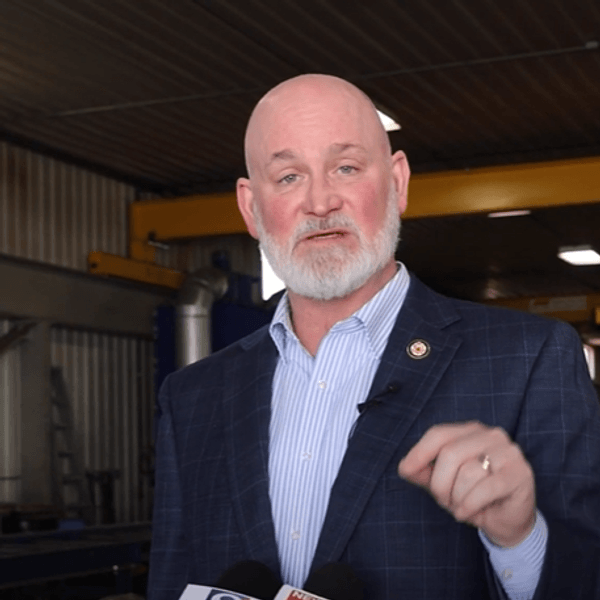

Note from the Publisher: Steve Early has been an organizer, strike strategist, labor educator, and lawyer. He recently retired from his job as national staff member of the Communications Workers of America. Early is the author of Civil Wars in U.S. Labor and Embedded with Organized Labor; his writing on the labor movement has appeared in many publications, like The Nation, The New York Times, The Wall Street Journal, and The Progressive.

To get information on upcoming editions of the Weekend Reader, sign up here to receive our free newsletter.