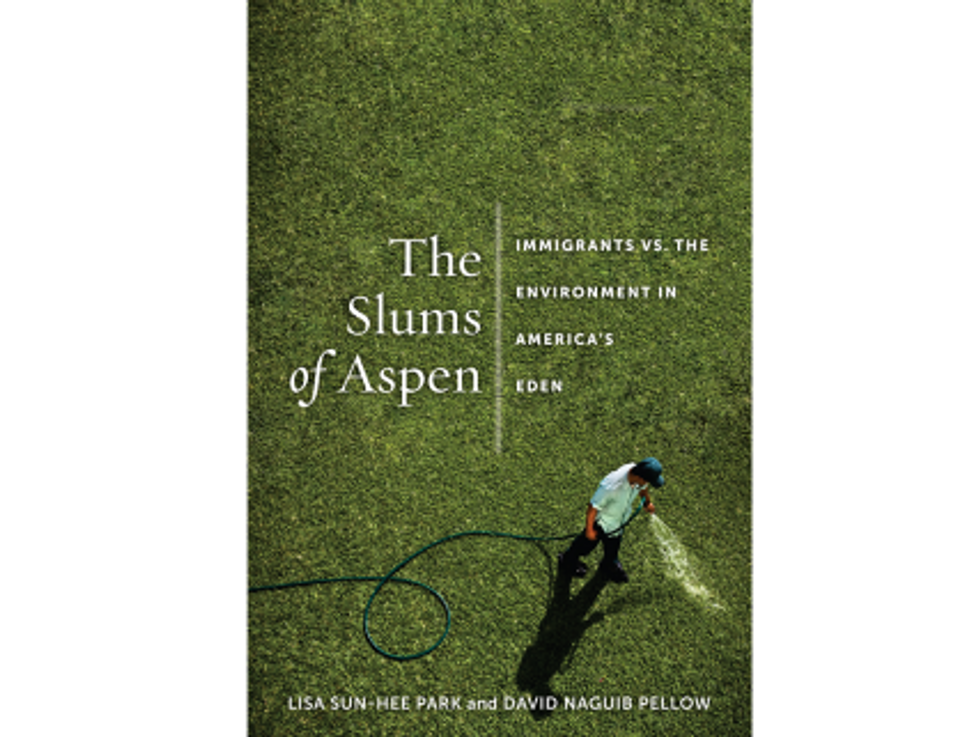

Weekend Reader:The Slums Of Aspen: Immigrants vs. The Environment In America’s Eden

This weekend, The Weekend Reader brings you The Slums Of Aspen: Immigrants vs. The Environment In America’s Eden by Lisa Sun-Hee Park and David Naguib Pellow. When Congress reconvenes in September, immigration reform will be one of the leading issues on everyone’s agenda. The bipartisan Gang of Eight immigration bill has received loads of criticism and concern from Republicans leaders who can’t agree with each other or Democrats on border security, a pathway to citizenship, employment verification, and reducing the distribution of visas. Above all of the debate, indecision, and bigotry, this is an issue that affects the lives of millions of immigrants.

Park and Pellow want to shed light on discrimination against immigrants and show how this issue is intertwined with the economy, civil rights, and even environmentalism. They conduct their own research and provide an impactful account of a wealthy Colorado community’s attempt to limit the number of immigrants in their neighborhoods and their reason for doing so: environmental protection. Environmental injustice is real and affects millions of immigrants and their families. Park and Pellow warn how resolutions like the one passed in Aspen, Colorado which you will read about below, can greatly impact communities… and what the rest of us can learn from this specific case study.

You can purchase the book here.

On December 13, 1999, the City Council of Aspen, Colorado—one of the country’s most exclusive recreational sites for some of the world’s wealthiest people—unanimously passed a resolution petitioning the U.S. Congress and the president to restrict the number of immigrants entering the United States. The language of the resolution suggests that this goal could be achieved by enforcing laws regulating undocumented immigration and reducing authorized immigration to 175,000 persons per year, down from the current annual level of between 700,000 and one million. One of their primary reasons for encouraging tougher immigration laws was the purported negative impact of immigrants on the nation’s ecosystems.

Concerns about immigration’s environmental impacts generally include such broad issues as urban/suburban sprawl, the loss of urban green space, and overdevelopment of wilderness and agricultural lands. In Aspen, more specific complaints include everything from car exhaust pollution associated with older model vehicles many immigrants drive (since workers drive anywhere from thirty to one hundred miles to labor in Aspen’s tourist industry), littering in mountain caves where some homeless immigrant workers sleep since affordable housing is nonexistent (the average sale price of a single family home in Aspen in 2000 was $3.8 million), to having too many babies (i.e., overpopulation), which some fear will contaminate the pristine culture that accompanies the stunning ecology of the Rocky Mountains. With an unemployment rate of 1.5 percent (in 2000), Aspen experienced severe labor shortages, and Latinos and other immigrants filled the many low-paying, seasonal jobs within the service industry. And, while there are a wide number of nationalities represented in the immigrant service economy of the Roaring Fork Valley, we focus on Latinos who comprise the majority of immigrants in the area.

The narratives that define immigration (particularly from Latin America) as a leading ecological threat also expose a profound irony: the everyday reality of this playground for the rich depends enormously upon low-wage immigrant labor. The luxury goods and services that distinguish Aspen, that make it a “world-class” resort town, are possible in large part because of the workers from all over the world who clean the goods and deliver the services and care for the people who buy them. In some respects, this is a bizarre story of a town that prides itself on being environmentally conscious, whose city council can approve the construction of yet another 10,000-square-foot vacation home with a heated outdoor driveway, and simultaneously decry as an eyesore the “ugly” trailer homes where low-income immigrants live. In other respects, this is a familiar story of America’s continuing clash between people of different races and classes, who rely on each other and yet cannot figure out how to live with each other. In still other respects, this is a story of the future, about the increasingly brutal inequality that will only become more pronounced as we negotiate the fast-paced global economy and its flows of money, ideas, and people.

From 2000 to 2004, we traveled up and down Aspen’s social pecking order. We conducted extensive archival and interview-based research to understand how people experience these contentious social issues. Our goal was to better understand the growing economic and racial inequalities from new vantage points, specifically from the perspective of environmentalists and immigrants. Our mission is to shed new light on these controversies, and to raise what we hope will be innovative, constructive questions that point to productive solutions.

Scholars and activists have, for four decades, presented evidence that people of color, as well as poor, working class, and indigenous communities face greater threats from pollution and industrial hazards than other groups. Environmental threats include municipal and hazardous waste incinerators, garbage dumps, coal-fired power plants, polluting manufacturing facilities, toxic schools, occupationally hazardous workplaces, substandard housing, uneven impacts of climate change, and the absence of healthy food sources. Marginalized communities tend to confront a disproportionate volume of these threats, what researchers and advocates have labeled environmental injustice and environmental racism. These communities are also more likely to be impacted by extractive industrial operations such as mining, large dams, and timber harvesting, as well as “natural” disasters like flooding, earthquakes, and hurricanes. We observe these patterns at the local, regional, national, and global scale, and the damage to public health, cultures, economies, and ecosystems from such activities is well documented. For example, immigrants and people of color in California’s Silicon Valley live in communities with disproportionately high concentrations of toxic superfund sites and water contamination, and work in jobs that expose them to disproportionately high volumes of hazardous chemicals. In Chicago, African Americans and Latinos live in neighborhoods with disproportionately high numbers of garbage dumps and other environmental hazards, and we see this pattern holding true for Asian Americans, Native Americans, and working-class whites nationally. The field of environmental justice studies has emerged as a means to consider the historical and contemporary drivers of environmental inequalities, its many manifestations, and as a vehicle to address this problem through research, action, and policy. Environmental justice studies span the fields of history, sociology, anthropology, law, communication, economics, literature, ethnic studies, public health, architecture, medicine, and many others. Activists and policymakers have also produced a great deal of research on environmental justice issues and have drawn on the work of scholars to pass laws and introduce state and corporate policies, which would confront some of the most glaring aspects of environmental injustice in the United States and globally.

Scholars have also demonstrated how communities have responded to such ecological violence creatively through protest, art, science, and sustainable development projects. Such work underscores how environmental injustices shape the politics of race, class, indigeneity, citizenship, gender, sexuality, and culture. While these studies reveal the hardships and suffering associated with environmental inequality and environmental racism, fewer studies consider the flipside, or source, of that reality: environmental privilege. Over the last several years we have been developing this concept, inspired by the work of scholars like William Freudenburg, Kenneth Gould, George Lipsitz, and Laura Pulido. We argue that environmental privilege results from the exercise of economic, political, and cultural power that some groups enjoy, which enables them exclusive access to coveted environmental amenities such as forests, parks, mountains, rivers, coastal property, open lands, and elite neighborhoods. Environmental privilege is embodied in the fact that some groups can access spaces and resources, which are protected from the kinds of ecological harm that other groups are forced to contend with everyday. These advantages include organic and pesticide-free foods, neighborhoods with healthier air quality, and energy and other products siphoned from the living environments of other peoples. In our study, we show how environmental privileges accrue to the few while environmental burdens confront the many, including lack of access to clean air, land, water, and open spaces.

If environmental racism and injustice are abundant and we can readily observe them around the world, then surely the same can be said for environmental privilege. We cannot have one without the other; they are two sides of the same coin. The authors of the groundbreaking United Nations Millennium Ecosystem Assessment articulate the relationship between environmental injustice and environmental privilege quite powerfully:

In numerous cases, it is the poor who suffer from the loss of environmental services due to the pressure exerted on natural systems for the benefit of other communities, often in other parts of the world. . . .The impact of climate change will be felt above all in the poorest parts of the world—for example, as it exacerbates drought and reduces agricultural production of the driest regions—while greenhouse gas emissions essentially come from rich populations.

Where there is pesticide poisoning of agricultural workers and eco-systems as a result of multinational chemical companies producing and forcing these toxins onto laborers and global South communities (via aid packages from international financial institutions), somewhere those who profit from these actions may be living and working in pesticide- free spaces, eating organic foods (the term “global South” is a mainly a social—rather than strictly geographic—designation meant to encompass politically and economically vulnerable communities). While some people are forced to live next door to a paint factory, a landfill, or an incinerator and breathe air that contributes to asthma and various respiratory diseases, others have the luxury of spending time in second homes in secluded semirural environs and can marvel at the fresh air they take in during a morning walk. Deforestation in the Amazon and Indonesia produces wood and paper products for people in far away places who live in far more comfortable surroundings, while the indigenous peoples whose land produces such goods confront genocide. Environmental privilege not only feeds off of environmental injustice, it is environmental injustice. The French journalist Hervé Kempf puts it this way: “We must . . . understand that the ecological crisis and the social crisis are two faces of the same disaster. And this disaster is implemented by a system of power that has no other objective than to maintain the privileges of the ruling classes.”

If you enjoyed this excerpt, you can purchase the full book here.

Excerpted from The Slums Of Aspen: Immigrants vs. The Environment In America’s Eden by Lisa Sun-Hee Park and David Naguib Pellow. Copyright © 2011 by New York University. With permission of the publisher, New York University Press.