By Esmeralda Bermudez, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

LOS ANGELES — The dishes she used to scrub after each family dinner pile up by the sink. The husband who sweetly called her his trophy wife cries alone in the room where he now sleeps. The 11-year-old son with big brown eyes who once cuddled on her lap now hardly comes near her.

She can’t move. She can’t talk. She can only blink her eyes.

Angie Bloomquist was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis less than two years ago. Since then, the fatal illness known as Lou Gehrig’s disease has shut down just about every muscle in her body. The toll on her family has been almost as devastating.

“It’s like a tornado ripped through our home,” Angie says. “And destroyed everything we built.”

She speaks through a special computer that tracks her eye movement, a painstaking task that exhausts her after a few sentences.

Still, in her final days, Angie finds herself pushing more than ever — for the choice to die through doctor-prescribed medication.

Proponents know it as “aid in dying.” Opponents call it assisted suicide. Since it was legalized in Oregon in 1994, there have been dozens of attempts to have similar versions approved in nearly 30 states. All have failed, except four: Washington, Vermont, Montana, and New Mexico.

In California, the issue hasn’t been brought before lawmakers or voters since 2007. This year, buoyed by the story of Brittany Maynard, who left her Bay Area home for Oregon to carry out her legally assisted death, supporters have geared up for another try.

One bill is making its way through the Legislature. Recently, two lawsuits were also filed against the state aiming to legally protect physicians.

Angie, who says she knew long before she was diagnosed that she would want to hasten her death if she became severely incapacitated, joined one of those lawsuits this month.

“I know how I want to live and know that that life is no longer possible,” she says. “The right to die should be my right.”

Continue reading

Angie’s symptoms began in early 2013, just before her 47th birthday.

The fingers on her right hand twitched and she had trouble typing. She became exhausted walking from the parking lot to her office at Miller Children’s Hospital in Long Beach, where she was a social worker. One day, leaving work, she inexplicably lost her balance and fell hard on a staircase.

In August 2013, after months of tests, Angie and Fred, her husband of 15 years, got the diagnosis: She had ALS.

“My heart sank and my body went cold,” Angie says. “Life, as we knew it, ceased to exist.”

The disease affects the brain and the spinal cord’s nerve cells. It eventually paralyzes sufferers, while their minds almost always remain unaffected.

About 30,000 Americans live with ALS. Half of them die within two to five years. Breathing gradually becomes more difficult, and often, patients suffocate. Cases like that of famed theoretical physicist Stephen Hawking, who has lived with the disease for more than 50 years, are a rare exception.

Angie, ever the realist, immediately began planning for her death. She had spent 23 years as a social worker, the last decade in hospitals watching children fight futile battles against ruthless diseases. She had guided families, preparing them for their child’s death.

Now, the time had come to guide her own.

On a recent day, Angie rests in her usual spot in the family’s television room. Fred walks through the 112-year-old Craftsman they share with their son, Andres, and their two dogs, Viejo and Peanut.

The sun is just about done setting over San Pedro. The jasmine climbing over the white picket fence Fred and Angie put up years ago fills their front yard with a sweet scent.

Fred turns on the light in the first bedroom.

“This is where the magic happens,” he says, in a not-so-funny tone. “Or at least, it used to.”

Their former bedroom is now Angie’s room. It has two twin beds: Angie’s hospital bed and, next to it, a bed for her overnight caretaker.

The dresser is packed with a mix of medications, tubes, wipes, drops, syringes.

Fred widened doorways, built a side deck and a wheelchair ramp and remodeled the bathroom to make room for a commode. Soon after Angie was diagnosed, he organized a ceremony to renew their vows. Beneath two white ash trees in their backyard, his wife giggled as he tried to explain, using the lyrics of his favorite love songs, how much he loved her.

“I’ve had some deliriously happy times in my marriage,” he says. “And I know that those moments, unlike the human body, are everlasting.”

Fred tries to be honest with Andres about what’s happening to Angie. But the truth is, most days, they avoid the topic.

“I’m not really the talking type,” Fred says.

He has to be strong for Angie — a woman who used to shush rowdy neighbors in her pajamas at 3 a.m. and throw bouncy castle parties for some 20-plus 5-year-olds. When he cries, he cries alone in his room, off the kitchen.

That’s the thing about losing the girl of your dreams. Day in, day out, it hurts like hell.

“I’m not going to reduce her to a few fanciful stories,” Fred says. “She was too vast, too great. She was a tidal wave.”

Continue reading

The Bloomquists thought of going to Oregon, but qualifying for the law could take months. Angie also considered refusing food and slowly drifting to her death through sedation, but that’s not how she wants to go.

The lawsuit is being handled by attorney Kathryn Tucker, executive director of the L.A.-based Disability Rights Legal Center, who’s overseen these kinds of cases on a national level for years.

Proponents are ready to go to the ballot in 2016 if the pending legislation fails. Tucker believes a court decision is the best way for California to win approval. She’s had recent success with similar lawsuits in Montana and New Mexico and has another one pending in New York.

Despite the traction supporters have gotten recently, the issue faces great opposition. Doctors, Catholic leaders and some disability rights advocates object on ethical, religious and medical grounds.

“If assisted suicide is approved, it would result in many lives ending without their consent,” says Marilyn Golden, senior policy analyst with the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund. “No safeguards have ever been enacted or proposed that can prevent that outcome, which can never be undone.”

Golden says combining a profit-hungry health care system with assisted suicide could result in patients being denied care and steered toward dying. Heirs and caregivers could also become abusive, and mentally ill or suicidal patients who are not terminal would have few safeguards to protect them from killing themselves.

Tucker says if the lawsuit succeeds, those safeguards — such as requiring a physician’s second opinion and judging metal competence — would be left for doctors to decide.

As for Angie, attorneys say they plan to lobby the court for a special permission to help her die as soon as possible — at her home, with her family by her side. She entered hospice care recently and may not have more than a few months to live.

“She’s accepted that this disease has brought her to the doorstep of death,” Tucker says. “She just wants to be able to have a measure of control to have a more dignified and peaceful death.”

Continue reading

Each day after Andres leaves for school and Fred heads to work, Angie’s three-hour routine begins. It takes her that long to move from her bed to the recliner in the television room.

Estella Ganuza, her morning caretaker, feeds her through a tube. It’s a struggle to not choke on her saliva.

Then, like a stork carrying a sleeping child, Ganuza uses a hydraulic machine with a giant sling to lift Angie’s limp body from the bed onto a commode. She wheels her into the shower, dresses her, combs her hair and transports her in the sling to her recliner.

Here, in the book-filled room where the family used to watch TV after dinner, she remains until night falls and it’s time to go to bed.

Her loved ones have stitched together a round-the-clock schedule of care, with one relative watching over Angie each day of the week. They bring food, do laundry, wash dishes, sweep the floors. Fred handles weekends.

Her mother massages her hands and feet. Her best friend from second grade goes on Costco runs. Her former hospital colleagues drop by and share stories that make Angie’s eyes light up.

“I love them and don’t know how I would have coped without their daily presence,” Angie says.

Her worst fear, she used to tell everyone, was losing her ability to speak.

How would she connect to the ones she loved the most?

When Angie’s speech went away about six months ago, she felt Andres begin to drift from her.

Maybe it’s his age. Maybe he just doesn’t know what to say or how to say goodbye.

He goes to therapy, at Angie’s request. He likes to play and joke with Fred. He’s a bright boy who says he’s proud of his mother, above all else, “for putting up with me.”

After school each day, he bolts through the front door, straight into the television room.

“Hi, Mom!” he says.

He leans over the recliner and, for the briefest moment, lays his head on Angie’s chest.

Angie closes her eyes.

(c)2015 Los Angeles Times, Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

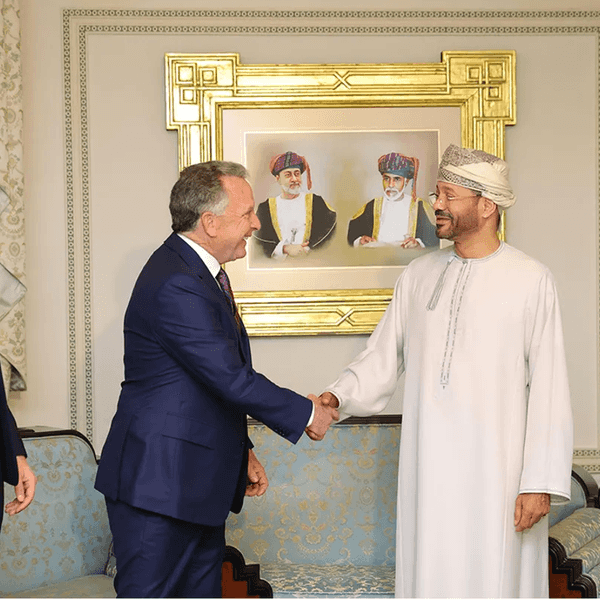

Photo: Fred Bloomquist reaches out to touch the cheek of his wife of 15 years, Angie, in their San Pedro home. “She’s my everything,” Fred said. (Katie Falkenberg/Los Angeles Times/TNS)