By John Heilemann, Bloomberg News (TNS)

WASHINGTON — Hillary Clinton had just exited the Iowa State Fair grounds on Saturday when I ambled over to the fair’s fabled soapbox and started gabbing with Michelle Gadbois and Tracy Garland. A married couple, both bone-deep Democrats, they were at the soapbox to catch Bernie Sanders, who would shortly be uncorking the blistering jeremiad that constitutes his stump speech. But Gadbois and Garland were not, in fact, #feelthebern-ers. They were Hillary — with caveats. “I want to be for her,” Tracy said, “but only if she pulls her head out of her ass and gets real.”

The projection of realness — naturalism, authenticity, approachability — on Clinton’s part has been a central aim of her campaign from the start. And especially so in Iowa, where the perception of her as distant, bloodless, and imperious played no small part in her crushing third-place finish in the 2008 caucuses. Her swing through the Hawkeye State this past weekend was replete with efforts at being (or, at least, seeming) real (or, at least, real-ish). She toured the fair without a rope line, wading into the crowd. She chatted and took selfies with voters. She gnawed on a pork chop on a stick. She gawked at the famous butter cow and petted a real one. Asked by a reporter to name her biggest campaign error so far, she smiled and said, “I’m just havin’ a good time.”

The first question about these and other gambits designed to present Iowans with a more relatable, accessible Clinton is whether they will be enough — enough to satisfy votes who share Garland’s reservations, enough to win the caucuses this time.

The second question is how much victory in Iowa really matters for Clinton, considering her daunting lead nationally and long-run advantages over Bernie Sanders, her only plausible challenger as of now.

The second question is easier to answer, and the answer is: a lot. For the prohibitive Democratic front-runner to lose the first contest in the nomination fight would be a major political and psychic blow. Especially given Sanders’s hailing-from-the- state-next-door strength in New Hampshire, it would appreciably increase the odds of Clinton being beaten there, too — and that, in turn, could create an establishment panic over her viability, with unpredictable and unpleasant consequences. Clinton’s people see all this clearly and are determined not to let it happen. Their focus on Iowa is more intense than is generally understood; though none of them would call the state a must-win, they are, in effect, treating it that way.

On the face of it, Clinton would seem to have little to fear from Sanders in Iowa. According to the most recent public poll, from CNN/ORC, she holds a commanding 50 to 31 percent lead. But the Clinton team recalls all too well what the passage of time has clouded in the memories of others: that her defeat in Iowa eight years ago was hardly foreordained; that deep into the fall of 2007, she led Barack Obama by as many as 11 points; that it wasn’t fully clear until the night of the caucuses just how badly Clinton had been outmatched by Team Obama’s superior organization, message, and, well, candidate.

The Clinton sharpies in Brooklyn and Des Moines are laboring to rectify each of these failings, and, on some, have made demonstrable headway. Led by Matt Paul, a veteran Iowa operative and protege to former governor Tom Vilsack, the campaign’s state operation is light years ahead of where its antecedent was in August 2007 — with 10 field offices, 50-plus paid staff, and more on the way after Labor Day. In terms of structural rigor, coordination, and grassroots savvy, former Iowa senator and recent Clinton endorser Tom Harkin tells me the organization taking shape is as good as Obama’s in 2008.

Clinton herself has come a long way, too. Unlike in 2007, when her events in Iowa were long on bombast and utterly impersonal, she has gamely undertaken a more intimate kind of voter contact this time around. Her hour-long march through the fair was, in truth, not the best example of this: between the Secret Service, Iowa state troopers, and media horde surrounding her, the procession was a roiling, heaving mess. But Clinton’s itineraries on her frequent trips to Iowa this year have revolved around town hall meetings, small group events, roundtables, and private house parties. By all accounts, she has excelled in such settings.

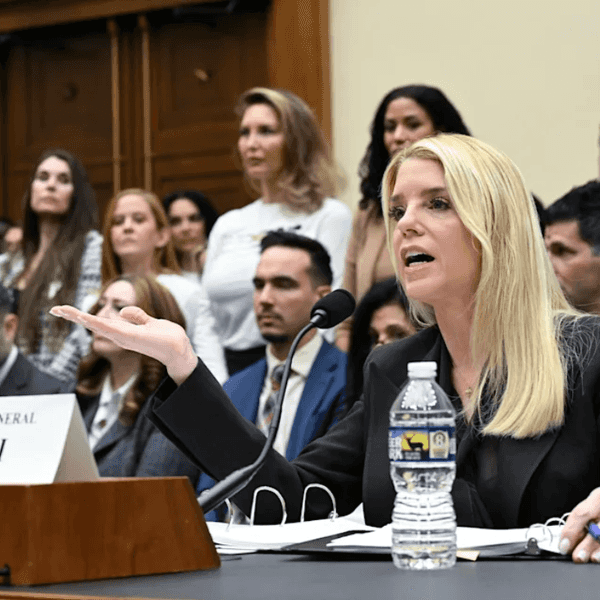

She also seems to be finding her form on the stump sooner than many expected. Last Friday night in Clear Lake, Clinton took part alongside Sanders, Martin O’Malley, and Lincoln Chafee in a Democratic fundraising dinner known as the Iowa Wing Ding (at which 2,000 partisans consume roughly 10,000 chicken airfoils). The speech she delivered was impressive in two important ways. First, it was a built on a message chassis that could rumble deep into the fall and beyond: an aggressive blend of middle-class populism and pointed attacks on an array of Republican 2016ers (Trump, Bush, Rubio, Walker).

Second, it was fiery, confident, emotional, energizing — precisely none of which adjectives could have been applied to a single speech of Clinton’s in all of 2007.

But Clinton’s speech at the Wing Ding was important for another reason: It marked a sharp shift toward defiance, bordering on belligerence, in her political posture regarding her private e-mail system. With clear echoes of her famous imputation of a “vast right-wing conspiracy” against her and her husband, she cast the investigations of that system as “the same old partisan games we’ve seen so many times before.” She also extended a metaphorical middle finger at anyone with even vague concerns about her unusual e-mail practices: “You may have seen that I recently launched a Snapchat account. I love it, I love it! Those messages disappear all by themselves.”

With those words and her campaign’s handling of the e-mail imbroglio overall, Clinton and her team have provided a vivid — and, to a growing number of Democrats, disconcerting — reminder of what hasn’t changed since 2008 about Hillary and Hillaryland, despite myriad changes in plans and personnel around her. The tone-deafness. The bunker mentality. The tendency toward a state of denial.

How all of this might affect Clinton electorally is impossible to know just yet. Her operation in and approach to Iowa seem predicated on the notion that the email issue is purely a chattering-class distraction, irrelevant to the real lives of real people. Certainly Hillary appears to believe this is the case. “It’s not anything that people talk to me about as I travel around the country,” she said blithely on Saturday at a media availability at the fair. “It is never raised in my town halls. It is never raised in my other meetings with people.”

And, who knows, it might be true and she may be right. But what Democrats are willing to say to Clinton’s face is different from what they are willing to say in private — what is weighing on their minds. Tracy Garland raised the subject with me unbidden. So did countless other Democrats, elite and rank-and-file, at the fair. Their queasiness with Clinton, their restiveness, is one reason that a 73-year-old Socialist has found himself with a wider opening than even he could have imagined. It’s also why Garland and Gadbois, among many others, were full of curiosity about whether Joe Biden or Al Gore might really, truly be about to enter the race.

If you were Clinton, you’d be sorely tempted to write this talk off, too, as yet more idle chatter. Or you could see it for what it is: a flashing red warning sign — in Iowa and beyond.

(c)2015 Bloomberg News. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Photo: U.S. Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton speaks at the Iowa Democratic Wing Ding dinner in Clear Lake, Iowa, United States, August 14, 2015. REUTERS/Jim Young