Trump economic adviser Kevin Hassett

In economist-speak, last Friday’s jobs report brought the “hard data” into line with the “soft data.” Before Friday, anecdotal evidence and independent surveys generally pointed to an economy facing major headwinds as a result of erratic policy, but official employment numbers still said that growth was solid.

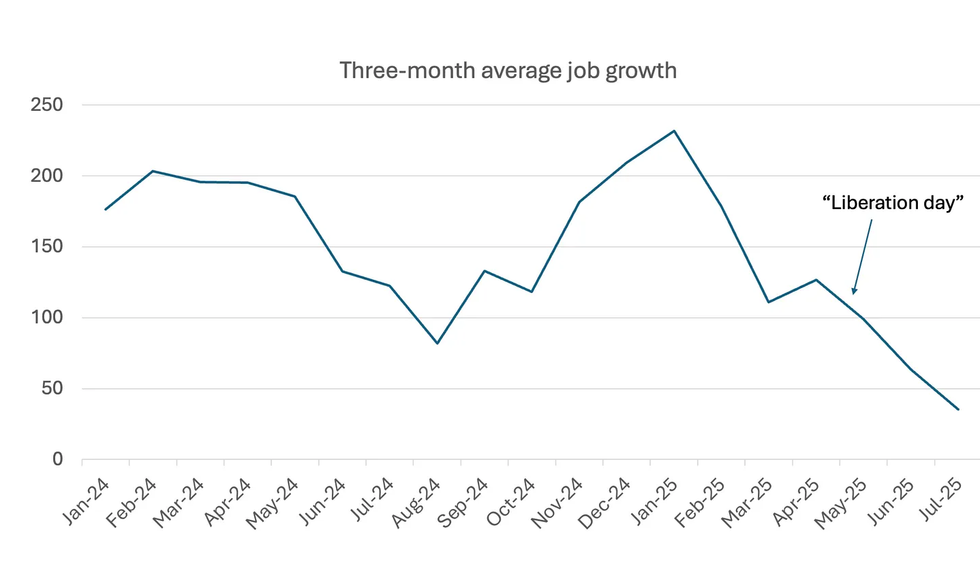

On Friday, however, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reported weak job growth in July and, more important, revised down its estimates for May and June. The official numbers now show a slowing economy — not a recession, at least yet, but a marked slowdown. Here’s the three-month moving average of job growth:

Most economists found this report entirely credible. The BLS has a sterling reputation for careful, objective analysis, and as I said, Friday’s report brought the official estimates into line with other evidence. What about those revisions? As Jared Berstein explained in a Substack post yesterday, revisions are normal. Without getting too deep into the weeds, the BLS wants to be timely, so it issues preliminary reports based on incomplete data, then routinely revises them as more data come in. Revisions tend to be especially large around turning points; what we saw Friday is exactly what we’d expect if the economy is in fact experiencing a significant slowdown, which would show up more strongly in revised data than in the initial reports.

But Donald Trump screamed “conspiracy” and fired the head of the BLS, because of course he did:

I don’t want to spend much time debunking Trump’s claim that there was a conspiracy to make the job numbers look bad. Suffice it to say that rigging the job numbers would be a complicated process, requiring the cooperation of many people, and we’d almost surely have whistleblowers telling us that it was happening. In fact, we will know that it’s happening when, as seems highly likely, Trump’s people politicize the BLS.

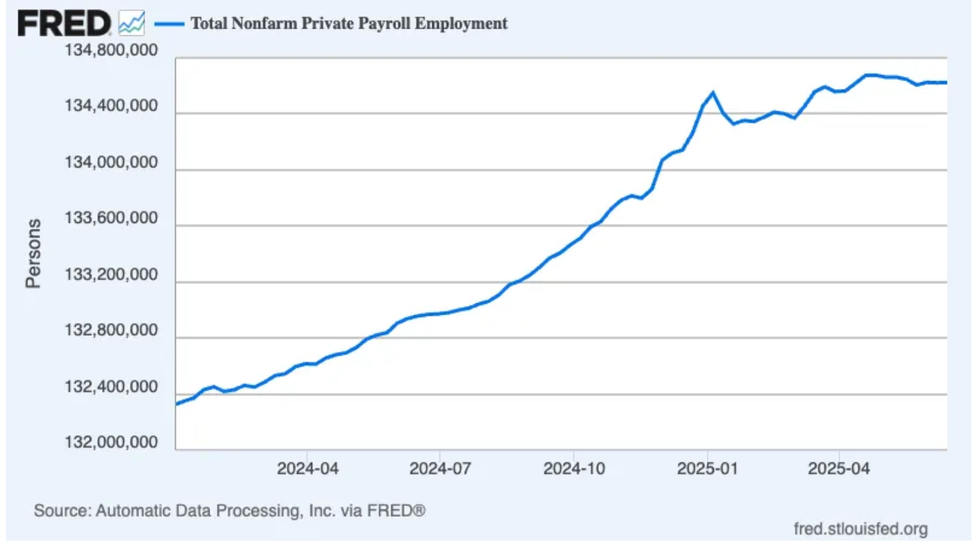

And as I said, independent indicators also point to a job slowdown. For example, Automatic Data Processing, which does many companies’ payrolls, produces independent estimates of private employment. People I know who follow these things closely consider ADP’s numbers noisy and less reliable than BLS, but if BLS were rigging the numbers to hide the glories of the Trump economy, we’d expect to see that hidden Trump boom in the ADP estimates. We don’t:

So Trump’s claim that disappointing economic numbers are fake news disseminated by radical leftists is ugly nonsense. But it was also predictable. Claiming that economic data you don’t like is fraud perpetrated by a deep state conspiracy has been standard practice on the right for a long time, going back to the “inflation truthers” of the Obama years.

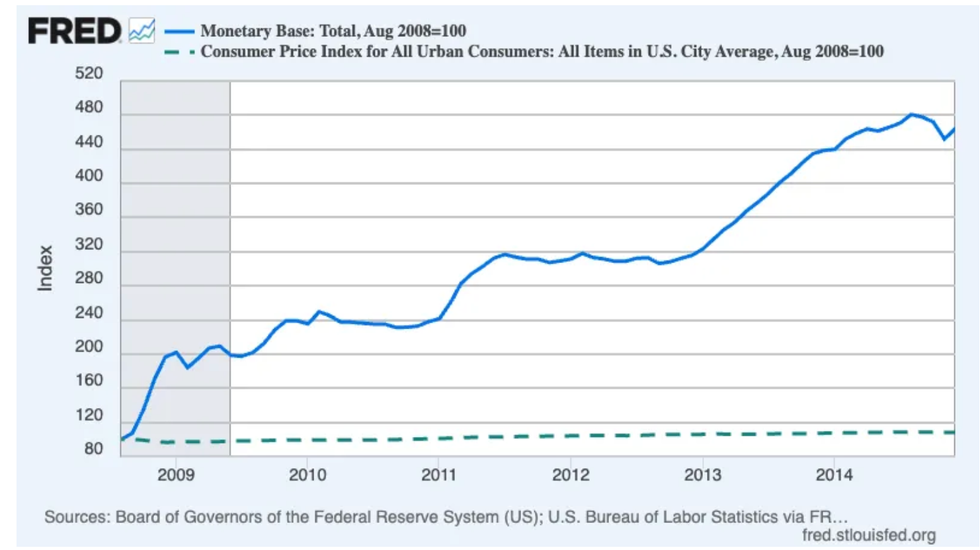

Here's the story: U.S. unemployment soared in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis. To mitigate the slump, the Obama administration enacted a fiscal stimulus program, while the Federal Reserve engaged in “quantitative easing” — roughly speaking, printing a lot of money.

Many on the right went wild, insisting that these moves would lead to runaway inflation, even hyperinflation. More or less Keynesian economists like me, however, dismissed these warnings. Our models said that in a depressed economy with high unemployment expansionary fiscal and monetary policy would not be inflationary — in fact, I warned that the Obama stimulus was much too small.

The Keynesians were right. Here, for example, is a comparison of the “monetary base” — bank reserves plus currency in circulation — with consumer prices in the aftermath of the financial crisis:

The big inflation Obama critics predicted just didn’t happen.

But rather than admit that they had been wrong and rethink their economic models, many on the right insisted that runaway inflation actually was happening, but that government statisticians were hiding the ugly truth. For a while many right-wingers were eagerly citing quack analysts — sort of the economics equivalent of anti-vaxxers or climate deniers — to support outlandish claims about inflation. And I’m talking about influential voices, not obscure fringe figures. For example, in 2010 the historian Niall Ferguson, whom many still consider an important public intellectual, insisted that the official numbers were wrong and “double-digit inflation is back.” As far as I know, he has never owned up to his mistake.

By the way, this isn’t a case of “everybody does it.” When inflation temporarily surged under Joe Biden, I’m not aware of any Democratic-leaning economist, inside or outside the administration, who denied the reality of the inflation numbers, let alone attributed them to a political conspiracy. The paranoid style in American economics is very much a right-wing thing.

And because on today’s right every accusation is a confession, I predicted even before Trump took office that his administration would do what he falsely accused Democrats of doing, and begin manipulating economic data.

However, even I didn’t expect Trump to react to the very first bad jobs number of his administration by summarily firing the commissioner of the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Nor did I expect Trump officials to be so blatant about their intention of politicizing the statistical agency.

But that’s what they’re doing. It took just hours for Trump’s chief economist to endorse his conspiracy theories and declare the administration’s intention to replace BLS staff with political loyalists. On CNBC Kevin Hassett, director of the National Economic Council, said that

All over the U.S. government, there have been people who have been resisting Trump everywhere they can

and declared that

To make sure that the data are as transparent and as reliable as possible, we’re going to get highly qualified people in there that have a fresh start and a fresh set of eyes on the problem

I assume that I’m not the only economist already looking for alternative data sources that we can use to figure out what’s happening behind the façade of the Potemkin economy Trump will surely try to create.

The thing is, Trump’s refusal to accept bad economic news and his likely attempt to corrupt official data probably won’t fool many people. But he is, of course, surrounded by people who will tell him what he wants to hear, so he may succeed in fooling himself. And this means that when the economy starts to have serious problems, Trump won’t even admit that bad things are happening, let alone make a serious effort to fix those problems.

Paul Krugman is a Nobel Prize-winning economist and former professor at MIT and Princeton who now teaches at the City University of New York's Graduate Center. From 2000 to 2024, he wrote a column for The New York Times. Please consider subscibing to his Substack, from which this post is reprinted with permission.

- 'Disastrous': Mass Firing Of Federal Employees Leaves 'Gaping Holes' In Government ›

- Consumer Confidence Falls As Voters Blame Trump For 'Chaos' ›

- Trump Economic Advisers: A Team Of Cowards - National Memo ›

- Danziger Draws - National Memo ›

- 'Perfect Guy': Bannon Thrilled By Trump Pick To Oversee Jobs Data - National Memo ›

- Trump 's Economy Is Losing Jobs, So He Wants A New Scorekeeper - National Memo ›

- Feeling Insecure At Work? That Fear Is Real -- And You Can Blame Trump - National Memo ›