If nothing else, the internet has exploded the myth of human rationality. Remember when Al Gore was going around talking about the “information superhighway”? Twenty years down the road, it’s more like the Freeway of Delusion.

British philosopher Bertrand Russell would not have been surprised. “Man is a rational animal — so at least we have been told,” he said. “Throughout a long life I have looked diligently for evidence in favor of this statement. So far, I have not had the good fortune to come across it.”

Russell was thinking of World War I.

Evidence of mass irrationality abounds. Absurd falsehoods and crackpot conspiracy theories once touted by street-corner eccentrics carrying hand-lettered signs now circle the globe at the speed of light. As recently as a generation ago, intellectual gatekeepers like CBS anchorman Walter Cronkite and NBC’s David Brinkley presided over the news divisions at their respective networks, and were widely believed to deliver accurate information.

“If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost Middle America,” President Lyndon Johnson allegedly said after a critical on-air editorial in 1968 questioning American claims to be winning in Vietnam. Some have disputed the quote. But the story resonates because its essence was true. People believed Uncle Walter. Within two weeks of the broadcast, LBJ decided not to run for reelection.

Such an outcome would be unthinkable today. The most influential pundits during the 2016 presidential election spoke Russian. And most of what they peddled was sheer make-believe: poisonous fictions about Hillary Clinton’s dismembering children while simultaneously being at death’s door due to her failing health, etc.

No internet, no Russian trolls.

Also, in all likelihood, no President Trump.

Mere journalism of the traditional kind hardly stands a chance. Indeed, if one had no other reason to subscribe to Facebook, it would be to track the remorseless march of folly across the political landscape. Just this morning, for example, I learned from one Facebook friend — a prominent local citizen — that Sharia law is sweeping the nation. Christian children are being converted to Islam in public schools, while Americans everywhere are forbidden to criticize the ideology of Osama bin Laden.

It’s a given that all Muslims are, by definition, terrorists.

So yes, the terrorists have won, thanks to the spineless traitors of the “Democrat Party.”

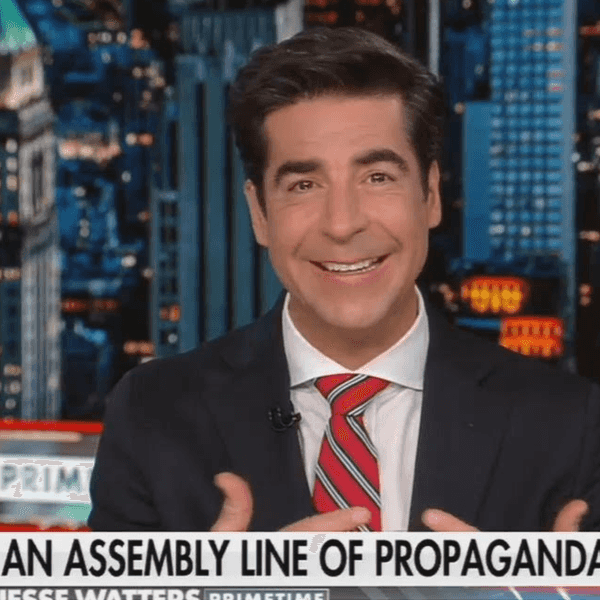

Lots of “likes,” and plenty of “shares.” Yes, a person would have to be intellectually disabled to believe this kind of crude propaganda. But it’s not really a matter of belief — or intellect. Fear of the “other” goes straight to the primitive core of the human brain, the “fight or flight” part. Arguing against it is like trying to talk a dog out of fearing thunderstorms. People are mainlining this drug all over the Internet. It’s a form of mass hysteria. By comparison, the staid Trumpists on Fox News resemble, yes, Walter Cronkite.

But here’s the deal. This particular example of psychotic propaganda almost certainly originated not in Russia, but right here in the USA.

According to an eye-opening report in The Atlantic by McKay Coppins, the production and dissemination of far-right internet memes has shifted to the United States. (Not that the Russians are out of business, far from it.) The Trump campaign in particular is operating a heavily funded Internet propaganda shop from the 14th floor of a gleaming high-rise just across the Potomac River in northern Virginia.

“Every presidential campaign sees its share of spin and misdirection,” Coppins explains, “but this year’s contest promises to be different. In conversations with political strategists and other experts, a dystopian picture of the general election comes into view — one shaped by coordinated bot attacks, Potemkin local-news sites, micro-targeted fearmongering, and anonymous mass texting.”

Given Trump’s personal fondness for conspiracy theories dating all the way back to the “birther” fable of Barack Obama’s mythical birthplace in Kenya, it’s to be expected that the GOP campaign will double down.

Coppins created a fake Facebook profile listing himself as a Trump supporter, and spent the impeachment trial absorbing what came over the transom. “I’d assumed that my skepticism and media literacy would inoculate me against such distortions,” he writes. “But I soon found myself reflexively questioning every headline … the notion of observable reality drifted further out of reach.”

At a deeper level, he explains, the purpose of flooding the zone with even the most absurd propaganda isn’t necessarily to persuade people of a particular line of thinking. It’s to instill in the body politic, as the political philosopher Hannah Arendt said about the followers of Hitler and Stalin, “a mixture of gullibility and cynicism.”

The goal isn’t so much loyalty as submission, she wrote: citizen/subjects who “believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and nothing was true.”

Crafted by 18th-century rationalists, the U.S. Constitution assumes a populace capable of recognizing its own enlightened self-interest and acting upon it. Can it survive the age of the Internet?

Good question.