On the same day, it was two very different scenes from Michigan.

The Detroit funeral last week of 5-year-old Skylar Madison Herbert, the young victim of COVID-19, received some notice, though in days that followed, other victims rapidly filled the screen and news pages. Yet it was impossible to forget young Skylar's beautiful face, soulful eyes and enchanting smile. Thinking that she would never again get to dress up in the Disney princess dresses and her mom's high heels that family members said she favored, or grow up to fulfill her dream of becoming a pediatric dentist — well, how could your heart not ache?

All that joy, all that potential stopped by a virus.

It is, of course, disturbing to read the data on how African Americans have been disproportionately affected by the pandemic. To see the photos, hear the memories and share the anguish over the death of this one young, black girl is quite simply a punch to the gut.

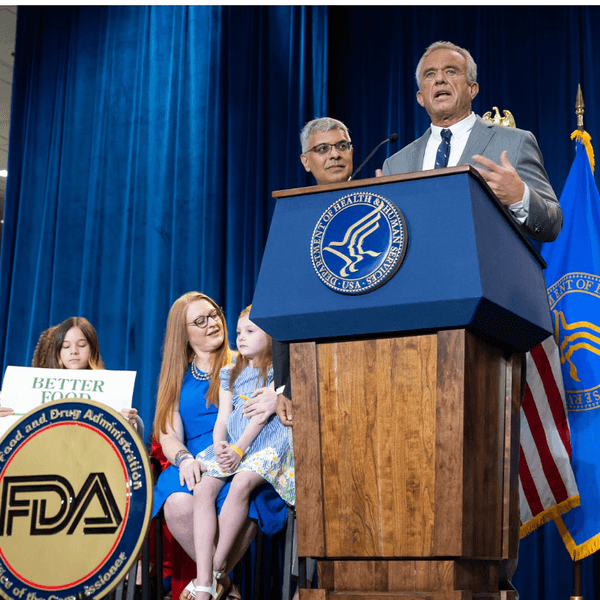

That same day, images of angry faces and armed protesters made for their own camera-ready moment. Hundreds marched on and into the Michigan state Capitol building in Lansing, holding signs that compared Democratic Gov. Gretchen Whitmer's stay-at-home orders to tyranny, chanting "Lock her up" and "Heil Whitmer," and claiming Second Amendment infringement while toting weapons. Their passion was focused on reopening the state for business, even as testing lags and workers such as Skylar's first-responder parents barely had time to grieve.

Volume 0%Meanwhile, Michigan's number of COVID cases has passed 44,000, with the death toll at more than 4,000 and climbing. America's structural inequity, which has caused the coronavirus to wreak havoc on black and brown Americans, who already suffered the most from adverse health outcomes before the global pandemic, did not seem to be on the minds or in the hearts of the loud protesters. Many of them wore no masks and made no attempt to stand six feet from anyone, as they shouted about their "freedom."

If they were not up to volunteering where their energy could make someone else's life better, perhaps they might have considered protesting for pay equity, more federal stimulus money for small businesses, child care relief, more protective equipment for those in "essential" jobs or an extension of unemployment benefits — or for more coordinated leadership from the federal government.

There was little sympathy for health care workers or those standing at fast-moving lines at the meat processing plants that have become virus hot spots. At some rallies, however, you could catch an occasional glimpse of a Confederate flag in that great Rebel state of — let me check where it was again — Michigan.

A common denominator

Now might be the time to mention what so many reports have left out: that the majority of the gun-toting crew, those lined up in front of the governor's office in a threatening tableau of intimidation, were white and male, exercising their rights without fear of retaliation.

Protest is as American as apple pie, though restraint is not usually the go-to reaction from law enforcement when Black Lives Matter activists and allies march with nothing more than signs and cell phones.

Even some of the Republican state legislators who are fighting Whitmer's pandemic executive orders had choice words for the Lansing protests. Mike Shirkey, the state Senate majority leader, criticized "so-called protestors who used intimidation and the threat of physical harm to stir up fear and feed rancor. I condemn their behavior and tactics. They do not represent the Senate Republicans. At best, those so-called protestors are a bunch of jackasses."

While Michigan has gotten much of the attention, protests are spreading across the country, some backed by conservative groups that seemed to be waiting for the opportunity COVID-19 provided. And for many of the marchers, ideology can trump logic.

In North Carolina, a leader of a group opposing Democratic Gov. Roy Cooper's stay-at-home measures confirmed she tested positive for the virus. She would not, however, comment on whether or not she attended weekly rallies in Raleigh and insisted that the quarantine violated her civil rights.

Not much on those unfortunate enough to have crossed her path, though Rep. Dan Bishop, R-N.C., attended and defended one such gathering.

No time for unity

Both Democratic and Republican governors nationwide have extended stay-at-home restrictions or started to reopen with varying levels of caution. But President Donald Trump selectively trains his most brutal attacks on Democrats, with an eye toward his own reelection, choosing to fight partisan battles in what he has labeled a war.

Instead of preaching unity when Americans are suffering across state lines, Trump echoes Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell's attempts to paint the virus and the federal stimulus as red or blue, as seen in the president's tweets to "LIBERATE" states such as Michigan.

Trump reached back to his Charlottesville, Virginia, playbook — when he labeled both neo-Nazis and counterprotesters as "very fine people" — in his response to the Michigan protests. "These are very good people, but they are angry," he said, urging Whitmer to "make a deal."

Trump might look to polls suggesting most Americans trust their governors and are hesitant about opening the country too soon.

The president is such a soft touch for those wearing MAGA gear; no such luck for peaceful protester Colin Kaepernick or fellow NFL players, who knelt, without weapons, to bring attention to racial injustice, and were cursed.

Of course, not all those marching in cities across the country are Trump-supporting, anti-vaxxers, with hard hearts toward leaders and fellow citizens who want to go slow. Many are afraid of the economic fallout of this health crisis; some just want to get out of the house, which is understandable. But the white-hot fury and anger at leaders trying their best to keep citizens safe is not.

Right now, most Americans can only dream of getting the testing available to the White House staff. In a rare note of agreement, Speaker Nancy Pelosi and McConnell agreed to decline the administration's offer to provide Congress with rapid testing, in order to "keep directing resources to the front-line facilities where they can do the most good the most quickly."

More testing and tracing are goals while scientists and medical professionals continue to work on promising treatments and a vaccine. (Plus, keep the mask on, Trump and sidekick Mike Pence.)

But the divisions in America are clearer than ever when, on one day in Michigan, two groups so close in geography were so far apart — one state and such different states of mind. I would be more optimistic that the lessons learned from this crisis would make America better if those protesters in Lansing had set down their weapons and paused for just a moment to respect the memory of a 5-year-old, who was, whether they liked it or not, one of their own.

Mary C. Curtis has worked at The New York Times, The Baltimore Sun, The Charlotte Observer, as national correspondent for Politics Daily, and is a senior facilitator with The OpEd Project. Follow her on Twitter @mcurtisnc3.

- Make America Think Again Protest Hat– The National Memo ›

- When Trump's Toy Soldiers March On State Capitols, Ignore Them ... ›

- Anti-Lockdown Protests 'Will Backfire,' Warns Dr. Fauci - National ... ›