Reprinted with permission from The Washington Monthly.

Within an hour of winning the House, Democrats were talking about infrastructure. “We will deliver a transformational investment in America’s infrastructure to create good paying jobs,” Nancy Pelosi declared after victory was assured. By the next day, politicians on both sides of the aisle were hailing infrastructure as a good place for compromise. On Wednesday, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell told reporters that infrastructure was “the one issue” where “there could be a possible bipartisan agreement.” The incoming chairman of the House Transportation Committee, Peter DeFazio, praised President Trump, who has regularly talked about working with Democrats to fix America’s infrastructure.

“Donald Trump is a builder,” DeFazio said. “He gets it.”

But he doesn’t.

Since Inauguration Day, the Trump administration’s infrastructure plan has been a one trillion dollar “public private partnership,” funded with $200 billion from Congress and with $800 billion in loans from Wall Street institutions like Goldman Sachs and Blackstone. The $200 billion paid by Congress would be quickly spent. But Wall Street says it would demand an annual interest rate of 10 to 12 percent on their loans. Getting a return on these large, Wall Street-funded infrastructure projects would be very expensive. It would be so expensive, in fact, that the women and men intended to use these new rail lines, benefit from new broadband networks, cross repaired bridges, or fly out of upgraded airports won’t be able to afford to do so.

Trump’s plan is a slap in the face to the mayors and governors who have been waiting decades for help funding infrastructure projects that their constituents need. Even if it weren’t prohibitively costly for communities, Trump’s plan doesn’t provide the full $1.5 trillion which the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) believes is outside the current capabilities of the states and municipalities. Trump has proposed a half-baked half-measure which won’t affordably solve our current problems, let alone address our future needs.

But while the nation’s infrastructure needs are great, they are not an emergency. Our infrastructure must be fixed in a timely matter, but not necessarily tomorrow. Democrats don’t have to settle with Trump on a bad plan, and they shouldn’t. They can instead push for a lasting solution. And thankfully, the party already has one in mind: an infrastructure bank.

As a term, “infrastructure bank” might sound boring. But the idea can be elegant and ingenious. The federal government first establishes a bank and seeds it with billions of dollars–a lot of money, but still only a small fraction of what Trump is proposing. Next, the bank invites outside investors to add more money–orders of magnitude more than what the government provided. The bank would then finance infrastructure projects across the country, so long as they pay for themselves over time through user fees or associated taxes. States or cities could apply to fund projects ranging from passenger trains and toll roads to electricity grids and sewage pipes. And unlike Trump’s proposal, an infrastructure bank would not be a one-off funding initiative. Rather, once seeded, it would be self-sustaining, as loan repayments from earlier projects allow the bank to lend money for future ones.

Every administration since Ronald Reagan’s has at least talked about a national infrastructure bank, and both Bill Clinton and Barack Obama initially pushed to create one. So why hasn’t it happened? For starters, it’s difficult to establish a bank structure that fully respects Congress’ right to appropriate but doesn’t unduly politicize project selection and project oversight.

Some people believe that Congress would be able to fairly and efficiently manage these decisions, but I’m not one of them. Members of Congress are very able to decide what they want funded. But they would be less focused on selecting good projects and more likely to select ones which favor their own region or political views on infrastructure.

I believe that a proper national infrastructure bank must instead be a wholly owned government corporation with non-partisan directors appointed by the president and confirmed by the Senate. These directors should be experts when it comes to infrastructure and macroeconomics. They should include women and men with proven expertise in heavy construction, business, labor and government policy. And in order to make the bank as informed as possible about America’s diverse infrastructure needs, the bank should, like the Federal Reserve, be regionalized into operating districts.

A second challenge for the bank will be melding project selection with current and future national needs. Not every road project should be approved, not every urban project should be favored, and certainly no project should irreparably damage the environment. The bank’s board will need to be Solomon-likein its stewardship. But by having experienced directors and devolving power across the country, the bank I’m proposing will more likely make the right calls than would either Congress or a Washington-centric band of technocrats.

Finally, the bank has to avoid leaving cities and states drowning in high-cost debt. To make sure this doesn’t happen, my proposed bank avoids Wall Street entirely. Instead, complemented by support from the U.S. Treasury, the bank would be primarily capitalized with and find its liquidity from $1.5 trillion in long-term loans from America’s large state and municipal pension plans, as well as by some of the world’s large overseas sovereign wealth funds (like Norway’s massive oil-rich permanent fund). The interest rate on these loans would be in the range of 3 to 4 percent. This may appear low, but it is actually consistent with the interest rate these plans and funds earned over the last decade on their fixed-income assets.

It would, in other words, be a good investment. And to meet these returns, cities and states won’t have to make tolls, tickets, and fees astronomically high. Unlike Trump’s plan, this bank would lead to infrastructure that is affordable for Americans.

To attract financial support from pension plans and sovereign wealth funds, the bank’s first $300 billion in losses would be shared fifty-fifty between the bank and the U.S. Treasury. But in reality, there should be very few losses, since historically major infrastructure projects have defaulted at a rate of just 1 percent or less.

And importantly, because of this low default rate, I believe that the federal Office of Management and Budget (or OMB) would, based on precedent, score for Congress only actual payments to the bank made by Treasury and only when they are made, which means that the ultimate “scoring” by OMB should be much less than $150 billion–and thus at very low net cost to America’s taxpayers.

For six consecutive administrations, presidents have had three overriding objectives for funding moneymaking infrastructure. First, finance all of the infrastructure projects that are beyond the capabilities of states and cities–not just some of them. Second, prioritize projects in a fair and efficient manner. Third, minimize the federal government’s contribution. The National Infrastructure Bank I’m proposing, with its specific characteristics, is designed to achieve these objectives. It will fund infrastructure that’s affordable, accessible, and dearly needed. It won’t drain federal coffers. Democrats in Congress should now show their leadership and reach out across the aisle and to President Trump to pass legislation that creates this institution.

At the same time, however, Democrats in Congress need to strongly resist pressure to cut a less than perfect deal. They should oppose infrastructure packages that leave some projects behind or that overburden user communities with exorbitant fees. While our nation’s infrastructure needs are great, they are not dire. We can afford to wait. And if President Trump and Senate Republicans refuse, or if they insist on the President’s unacceptably costly and unfair pro-Wall Street plan, then Democrats should wait until they control both chambers of Congress and until we have a new President. American infrastructure has had too many patchwork fixes. It’s time we get this right.

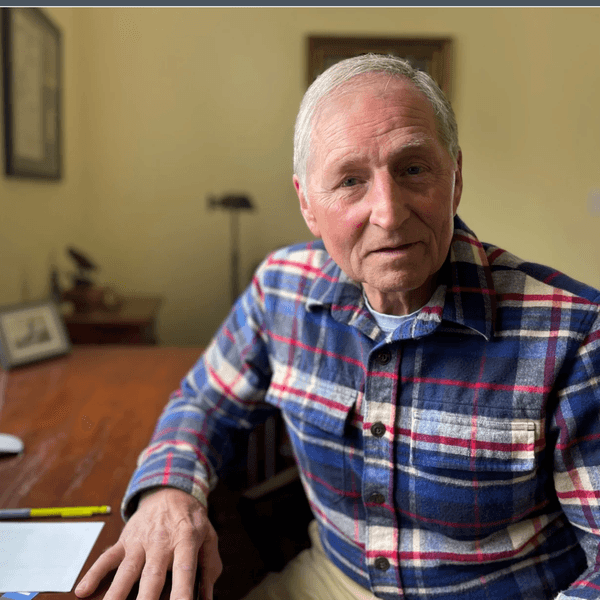

Leo Hindery, Jr. is co-chair of the Task Force on Jobs Creation, founder of Jobs First 2012, and a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. He is the former CEO of AT&T Broadband and its predecessor Tele-Communications, Inc. (TCI).

Header image by Kidkutsmedia/Flickr