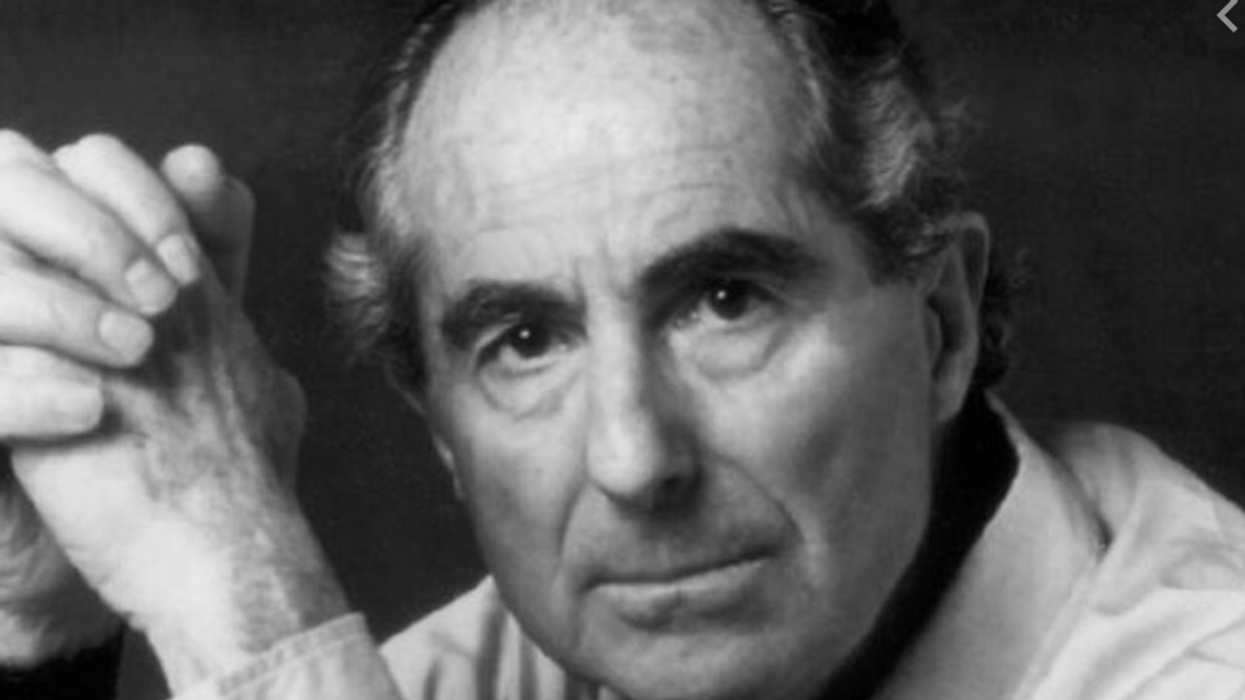

Philip Roth

As a rule, I read few biographies, and certainly not of authors, people whose most significant life events are spent alone. In my case, Churchill, Swift, and Dostoyevsky are the exceptions that prove the rule; world-historical figures who can't be understood outside the context of their times.

So I'd already decided not to bother with Blake Bailey's ballyhooed new book, Philip Roth: The Biography—even though Roth was a friendly acquaintance who'd given me help and encouragement way back when. After all, his novels were semi-autobiographical; his memoirs a veritable hall of mirrors.

I agreed entirely with what Bill Clinton said in awarding Roth the National Medal of Arts: "What James Joyce did for Dublin, what William Faulkner did for Yoknapatawpha County, Philip Roth has done for Newark." (Actually, historian Eric Alterman wrote the lines.) Roth rendered the city's dense particularity universal through the stories he told.

To know Roth at his best, read his 1997 novel American Pastoral, a penetrating portrayal of the "the indigenous American berserk" of the 1960s.

Actually, it was Newark that got us acquainted. I'd reviewed his baseball book The Great American Novel, stressing that he wasn't so much a "Jewish novelist"—a label he resisted—as a "New Jersey regionalist."

New Jersey, the Smart Aleck State.

He wrote asking how somebody in Arkansas knew all that, and urged me to expand upon the theme. The result was an essay called "The Artificial Jewboy," about growing up Irish-Catholic among Jews in neighboring Elizabeth. (One character in American Pastoral, a former Miss New Jersey, has my exact biography, right down to St. Genevieve's parish.) My essay contains more clumsy sentences and awkward kicks at the stars than the rest of the book it's printed in. But Roth saw something worthwhile and helped get it published. I've remained eternally grateful.

He'd even helped me see an aspect of my wife's character I'd taken for granted. After a long lunch at his country place in Connecticut, we'd gone for a walk in the woods. An excellent mimic, Roth could be terribly funny. He got Diane in a single take. What he liked most about her, he said, was her reserve.

"She doesn't care how famous I am," he said. "She's trying to figure out if she likes me in spite of it."

He thought that she hadn't yet decided.

That's Diane, who tended to be leery of literary narcissists based upon a couple of hard-drinking celebrity authors we'd encountered along the way.

Through her daddy the coach, I told him, she'd grown up knowing famous ballplayers. Roth respected that. Groupies are the bane of all famous people.

Anyway, although we'd lost touch years before he died in 2018, I figured I had no need to read his biography.

I knew he'd had a couple of terrible marriages; for all his perceptiveness, he appeared to have terrible judgement about women. Or maybe it was a two-way street, as in my experience of life, it normally is. He'd always had fierce critics among feminists and professional Jews: the very fiercest have tended to be both.

A literary provocateur, Roth was far too easily provoked.

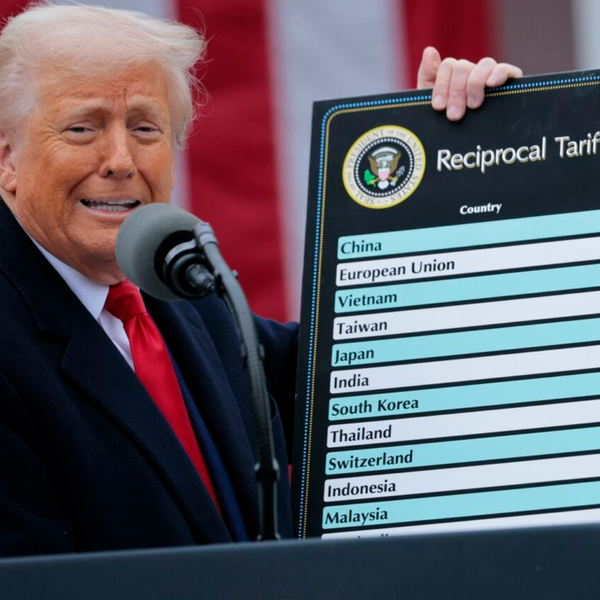

How bitterly ironic, then, that his seeming need to win arguments even after death led him to choose an authorized biographer who, within weeks of his book's successful launch, stood accused of rape and everything short of child molesting by a chorus of women—many of whom he'd pursued starting when they were his eighth grade students in a New Orleans middle school.

Faced with those accusations, which Blake Bailey and his attorney vigorously (if none too persuasively) deny, publisher W.W. Norton abruptly took the book out of print. At one level, the affair resembles Roth's novel The Human Stain, about a professor hounded for using the word "spook" (in the sense of "ghost") to describe missing students who turned out to be Black.

Is it right to "cancel" a book because the author's a creep? Put that way, no. The book exists independent of its author. As Eric Alterman puts it, "Many writers are terrible people. (I am perhaps not so great, myself.)"

I'll second that.

Or at least I would have before reading Eve Payton Crawford's Slate essay about Blake Bailey, her eighth grade teacher who raped her when she was a college girl of 19. "You really can't blame me," he said when she cried. "I've wanted you since the day we met."

She was 12 that day. "I still wore underwear with Minnie Mouse on them," Crawford writes. Along with an exhaustively-reported companion piece titled "Mr. Bailey's Class," Slate depicts a sexual predator in action, flattering young teens and becoming deeply involved in their personal lives for years before making his move.

A very sick puppy who made the mistake of soliciting fame, and the fate of whose Philip Roth biography interests me not at all.