As if he hadn’t already broken just about every rule of conventional politics (and common decency), Donald Trump decided at the last debate to plow through a guardrail of American democracy that has stood since the Civil War. In the final face-to-face encounter with Hillary Clinton, he refused to pledge to accept the results of the election.

Though audience members gasped at that display of utter contempt for the U.S. Constitution, it shouldn’t have come as a surprise. Trump has claimed for some time that the election is “rigged” against him.

As his poll numbers keep sinking, his claims of fraud and illegitimacy keep rising. At every rally, he warns his supporters that a vast conspiracy comprising Clinton allies, the news media and numerous unnamed co-conspirators has been working assiduously to keep him from his rightful place in the Oval Office.

Here’s the irony: There are, indeed, some shenanigans undermining the electoral process, some nefarious machinations meant to skew the vote. But this chicanery isn’t aimed at defeating Trump; rather, the strategy is being carried out by GOP politicians and operatives who, for the most part, want to see him elected.

In other words, the only widespread “rigging” that has taken place over the last decade has been conducted by the Republican Party, which has made a concerted effort to suppress the vote among the poor, the young and the elderly — all constituencies that tend to support Democrats. Having given up on enlarging their tent to attract more voters, the GOP has settled on a strategy of blocking the franchise for those whom it cannot win over.

This is a decades-old effort that goes back at least as far as the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. But Republicans took to it in earnest over the last decade, when it became clear that demographic changes would make it difficult for the GOP to continue as a major party, given its history of alienating black Americans and other ethnic minorities.

The strategy of instituting photo ID laws gained currency in the early 2000s, when GOP operatives in states such as South Dakota wielded it as a weapon to suppress the votes of Native Americans. Republicans were disappointed in the re-election of Democrat Tim Johnson, who won his 2002 race for the U.S. Senate by just 524 votes — with a huge turnout on reservations.

The lesson was this: Shaving off just a few hundred votes could boost the prospects of GOP challengers.

Requiring photo IDs worked because it seemed legitimate: Republican proponents claimed that they were only trying to protect the integrity of the ballot, to ensure against voter fraud. Never mind that voter fraud is very rare; the sort of in-person fraud that photo IDs would prevent is virtually non-existent.

Still, the idea had a superficial appeal. Middle-class voters take driver’s licenses for granted; they find it hard to imagine that a significant portion of the population — voters who are disproportionately black or brown — doesn’t own cars. They also find it hard to fathom the difficulty that the impoverished have in trying to obtain a government-sponsored ID.

Even federal courts became convinced that voter ID laws were necessary to crack down on fraud. Though he has since expressed regret for that decision, then-Supreme Court Justice John Paul Stevens wrote the majority ruling that endorsed Indiana’s strict voter ID law in 2005.

When Republican governors and legislators gained power in the 2010 elections, they took to voter ID laws with alacrity. According to New York University’s Brennan Center for Justice, in the last six years, nearly half the states passed laws making it more difficult to cast a ballot.

And GOP strategists were conscientious about aiming those laws at the voters most likely to support Democrats. In Texas, for example, student IDs from universities are not acceptable at the polls, but concealed gun permits are acceptable. (A federal court has ordered modifications to Texas’ law.) Guess which group is more likely to vote for Republicans?

Cynthia Tucker won the Pulitzer Prize for commentary in 2007. She can be reached at cynthia@cynthiatucker.com.

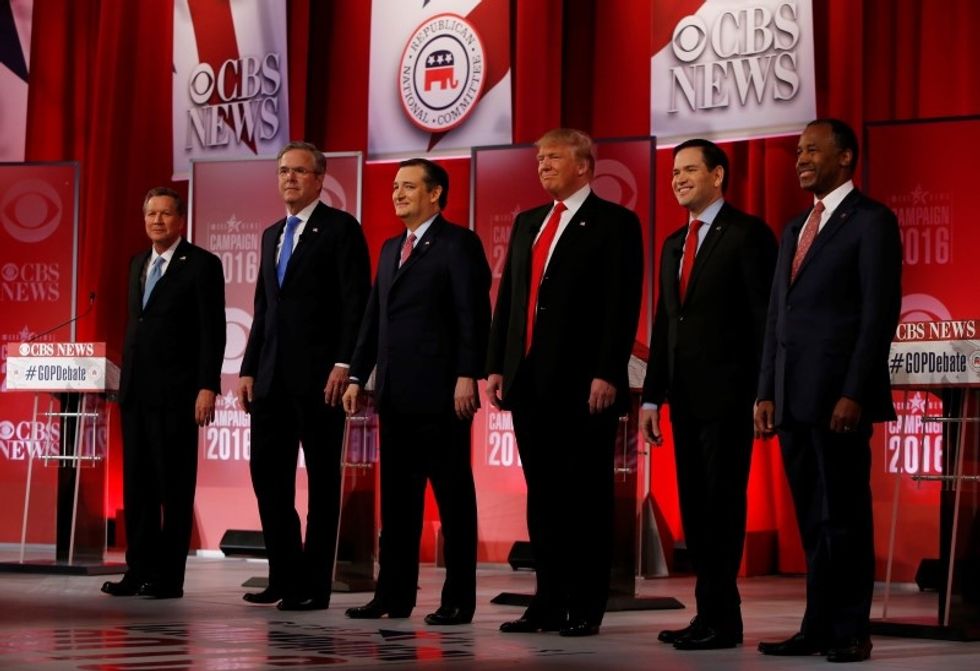

Photo: The remaining Republican presidential candidates, (L-R) Governor John Kasich, former Governor Jeb Bush, Senator Ted Cruz, businessman Donald Trump, Senator Marco Rubio and Dr. Ben Carson pose before the start of the Republican U.S. presidential candidates debate sponsored by CBS News and the Republican National Committee in Greenville, South Carolina February 13, 2016. REUTERS/Jonathan Ernst