Racism Pervades Our Institutions, Yet All Are ‘Innocent’

We will get to Baltimore in a moment. First, let’s talk about innocence.

That’s the unlikely ideal two great polemicists, writing over half a century apart, both invoked to describe America’s racial dynamic. It’s a coincidence that feels significant and not particularly coincidental.

In 1963’s “The Fire Next Time,” James Baldwin writes, “… and this is the crime of which I accuse my country and my countrymen, and for which neither I nor time nor history will ever forgive them, that they have destroyed and are destroying hundreds of thousands of lives and do not know it and do not want to know it. … But it is not permissible that the authors of devastation should also be innocent. It is the innocence which constitutes the crime.”

In 2015’s “Between the World and Me,” Ta-Nehisi Coates muses about the possibility of being killed under color of authority: “And no one would be brought to account for this destruction, because my death would not be the fault of any human but the fault of some unfortunate but immutable fact of ‘race,’ imposed upon an innocent country by the inscrutable judgment of invisible gods. The earthquake cannot be subpoenaed. The typhoon will not bend under indictment.”

It simplifies only slightly to say that what both men were describing is the phenomenon sometimes called institutional, structural or systemic racism.

Which brings us to Baltimore and a scathing new Justice Department report on its police department. The government found that the city’s police have a long pattern of harassing African-Americans and that oversight and accountability have been virtually nonexistent.

Indeed, the Constitution must have been looking the other way when an officer struck in the face a restrained youth who was in a hospital awaiting mental evaluation, when police arrested people who were doing nothing more sinister than talking on a public sidewalk, when they tasered people who were handcuffed. Not to mention the time a cop strip-searched a teenager on the street as his girlfriend looked on and, after the boy filed a complaint, threw him against a wall and repeated the humiliation, this time cupping his genitals for good measure.

It’s all outrageous stuff. But to understand the deeper outrage, you must realize that this happened in a city where 63 percent of the people — and 42 percent of the police — are African-American.

You will seldom see a sharper picture, then, of systemic bias. If the term confuses you, ask yourself: Who is responsible for this? Who gave the order that let it happen?

No name suggests itself, of course, and that’s the point. The assumption that black people are less educable, loan-worthy or deserving of their constitutional rights is baked into our systems of education, banking and policing. If you’re a teacher, a banker, a cop — even a black one — you swiftly learn that there are ways this institution treats African-Americans, and that if you want to thrive, you will conform.

There is no longer a Bull Connor or Strom Thurmond preaching this, nor any need for them. Somehow, the racism just … happens. Somehow, it just … is.

Changing the way it is will require more than good intentions; it will require sustained and purposeful action. But the alternative is a world where a cop feels free to grope a bare-butt black boy on a public street. Yes, the cop is guilty of the groping, but who stands accountable for his sense of freedom to do so? On that point, many of us grow tellingly mute.

“The earthquake cannot be subpoenaed,” writes Coates.

But Baldwin was right. It is, indeed, the innocence that constitutes the crime.

(Leonard Pitts is a columnist for The Miami Herald, 1 Herald Plaza, Miami, Fla., 33132. Readers may contact him via e-mail at lpitts@miamiherald.com.)

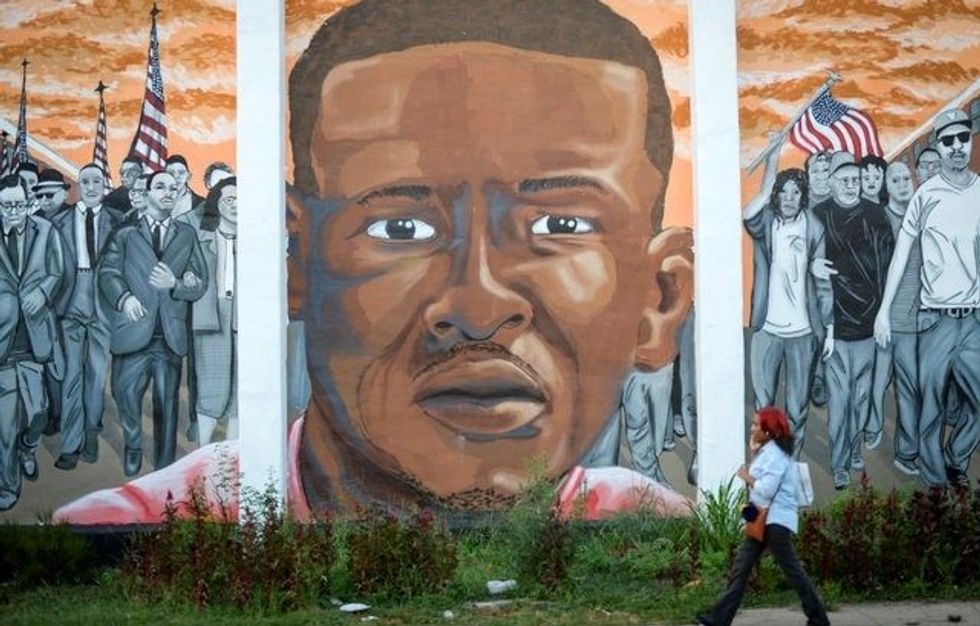

Photo: A woman talks on her cell phone as she passes a mural of the late Freddie Gray in the Sandtown neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland, U.S., July 27, 2016. REUTERS/Bryan Woolston