Why War To Impose Regime Change On Iran Will Bring 'A World Of Hurt'

At West Point, that’s what we used to call getting into a situation that was way over your head. It meant there was practically no way you were going to get out of the trouble you were in. No matter which way you turned or what you did, punishment and humiliation beckoned.

It’s what the United States found itself in the day in March of 1965 that Lyndon Johnson ordered the Third Marine Division into Vietnam. It’s where we were headed a few months later in July when Johnson increased our commitment of troops to 125,000 and doubled the monthly draft call-up to 1,000 young men per month. In that same month of March, Johnson ordered Operation Rolling Thunder, the carpet-bombing of “Communist strongholds” in South Vietnam.

A year later, our military presence in Vietnam was 385,000, and Secretary of Defense McNamara had initiated Project 100,000, recruiting and drafting soldiers who were below previous mental, medical, and behavior standards to meet new manpower goals demanded by the war.

Within two years of starting the war in Vietnam, we were in a world of hurt.

Seven years later, the United States military would go down to defeat by North Vietnamese and Viet Cong forces. Two years after that, the last helicopter would lift off the U.S. embassy in Saigon, and our military presence in that country would end completely.

On March 20, 2003, another U.S. Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, would oversee the invasion of Iraq. The initial air attack on Iraqi forces and military and political headquarters in Baghdad, dubbed “Shock and Awe,” was said to have succeeded spectacularly. Three weeks later, Rumsfeld would announce that U.S. forces had “taken Baghdad.” The war that was planned as a lightning strike to topple Saddam Hussein and “bring democracy to the Middle East” had worked!

But the thing about wars like those in Vietnam and Iraq is that the other side gets a say. In Iraq, Rumsfeld tried to avoid the fact that Iraqis were fighting back, even going so far as to ban the use of the word “insurgency” by the so-called Coalition Provisional Authority, the makeshift operation that had been established to administer the defeated country of Iraq.

Four years later, on January 10, 2007, President Bush announced a “surge” of 21,000 new American combat troops into Iraq to deal with Rumsfeld’s forbidden word, the insurgency that had arisen and was leading to the deaths of American soldiers every day.

About two years later, on December 4, 2008, the U.S. agreed with a new Iraqi government that U.S. forces would withdraw from Iraqi cities by the middle of 2009 and be gone from the country altogether by the end of 20ll. By June of 2009, 38 U.S. military bases had been turned over to the Iraqi government and U.S. forces had withdrawn from Baghdad. In the Vietnam war, withdrawal of U.S. forces from combat was called “Vietnamization.” In Iraq, it was called a “Status of Forces Agreement.”

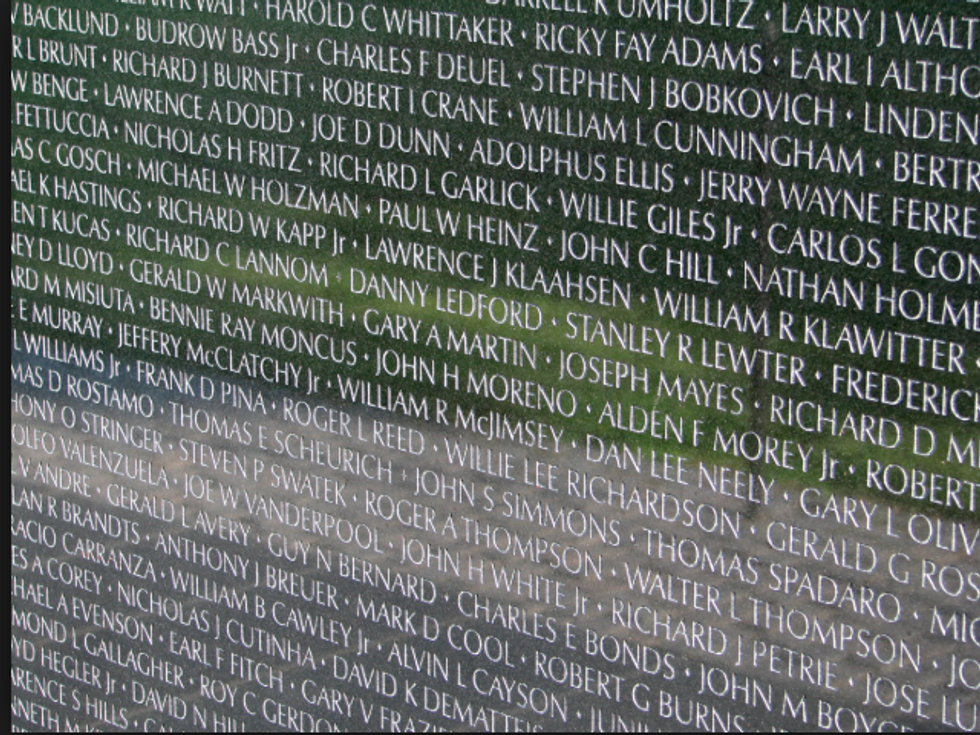

More than 58,000 American soldiers were killed in Vietnam. In Iraq, more than 4,000 members of the U.S. military were killed. Tens of thousands were wounded in Iraq. Hundreds of thousands were wounded in Vietnam.

In both countries, the United States had found itself in a world of hurt and withdrew with America’s tail between American legs.

Is it possible to learn from the past, from mistakes made by previous administrations and by previous Congresses that approved the trillions spent for, well…for nothing?

That is the question we face today all over again, as Donald Trump gets to turn the White House Situation Room into his personal playground and plan his way into another American misadventure, this time in the country of Iran.

Here are some handy facts and figures that I can guarantee are not being discussed down there in that Situation Room.

Vietnam in 1965 had a population of 38 million. In 1966, the country we said we were defending from Communism had a landmass of 66,000 square miles. There are no specific figures for Vietnam’s GDP in 1965, but by 1984, Vietnam’s GDP was only $18 billion, with a per capita GDP somewhere between $200 and $300. These figures of course suggest that Vietnam’s GDP twenty years earlier when we invaded was significantly lower.

In 2003, the population of Iraq was 27 million, and its landmass was 170,000 square miles. Iraq’s GDP that year was $22 billion. Its per capita GDP was only $818.

Those are figures for the years the great, big, powerful United States of America decided to invade those two countries.

Now let’s have a look at Iran in 2025. Iran is approximately four times the size of Iraq, with a territory of 636,000 square miles. Its population is 92.5 million, approximately three times the size of Iraq’s population the year we launched our invasion in 2003. Iran’s GDP is $1.75 trillion, about three-fourths the size of Russia’s GDP. Iran’s per capita GDP is $20,000, larger than Russia’s per capita GDP of $14,000.

All these figures indicate the relative strengths of countries to fight back against an invasion like one by the almighty United States. Iraq, when we invaded, was far weaker than the Iran of today. And that goes double or triple for the poor agrarian country of Vietnam in 1965 when an American president thought defeating Communism in that country would be easy.

So that’s who Donald Trump and his Secretary of Defense, Pete Hegseth, are thinking about going to war with. Oh, wait a minute! I’m sorry! It’s all over the news tonight that Hegseth and Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard are not in Trump’s “inner circle” of advisors, as he prepares for whatever he’s planning on doing as soon as this weekend.

That is when the U.S. will launch a massive air assault on Iran, according to a report by Seymour Hersh tonight. There will be “heavy American bombing,” according to what key U.S. and Israeli sources Hersh has “relied upon for decades.” Hersh is the author of “The Samson Option,” the authoritative 1991 book about how Israel built its nuclear arsenal and “America’s willingness to keep the project secret,” so it is apparent that Hersh’s sources in both Israel and the U.S. defense establishment are good ones.

Hersh has written a piece titled “What I have been told is coming in Iran,” on his Substack. Hersh reports that Trump has “signed off on an all-out bombing campaign,” but it won’t happen until this weekend because “the president wants the shock of the bombing to be diminished as much as possible by the opening of Wall Street trading on Monday.”

Does that sound like Donald Trump, or what? The timing of an “all out” attack on the most populous nation with the most powerful military in the Middle East will be timed not on tactical considerations, but on the fucking stock market.

Hersh reminds us that there are more than two dozen U.S. air force bases and navy ports in the Middle East which are no doubt being prepared right now for Iranian retaliatory strikes. Already, military dependents have been flown out of bases like the ones in Qatar and Kuwait. All the air forces bases in the region contain pre-positioned military “assets,” as they are called, that can be used in the air assault on Iran.

Hersh reports that the U.S. will strike “the bases of the Republican Guards,” the elite Iranian military force which protects Iran’s political and religious leadership. Trump killed General Qasem Soleimani, one of the top leaders in Iraq’s Revolutionary Guards in a drone strike on a vehicle carrying him at the Baghdad Airport in 2020.

Hersh reports that there is some confusion about Trump’s intentions if Iran’s Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei “departs.” Hersh reports that he was “told that his [Khamenei’s] personal plane left Tehran airport headed for Oman early Wednesday morning, accompanied by two fighter planes, but it is not known whether he was aboard.” Trump has demanded that Khamenei agree to an “unconditional surrender.” We are not at war with Iran, at least not on this day, Thursday, two days before the weekend that Hersh says the U.S. intends to launch a massive air strike on Iran, so it is unclear who Khamenei would “surrender” to and why.

If Khamenei has “departed,” it would seem unclear if Trump’s plans for a massive air attack on Iran will go forward. But the plans for dropping the famed “bunker buster” bomb on Iran’s key nuclear facility at Fordow seem to be very much alive, and Hersh quotes another “informed official” saying of the plans for the American attack, “This is a chance to do away with this regime once and for all, and so we might as well go big."

Hersh compares what might happen in Iran to Libya in 2011 after “western intervention,” when Gaddafi was killed and the country descended into chaos. As he ominously puts it, “The futures of Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon, all victims of repeated outside attacks, are far from settled,” indicating that an American assault on Iran that takes out its political and religious leadership might plunge a huge portion of the Middle East into chaos.

“Donald Trump clearly wants an international win he can market,” Hersh concludes.

That’s what Lyndon Johnson was hoping for in 1965. It’s what George W. Bush and Donald Rumsfeld thought they were getting when they ordered the invasion of Iraq in 2003. A big air campaign and a quick win.

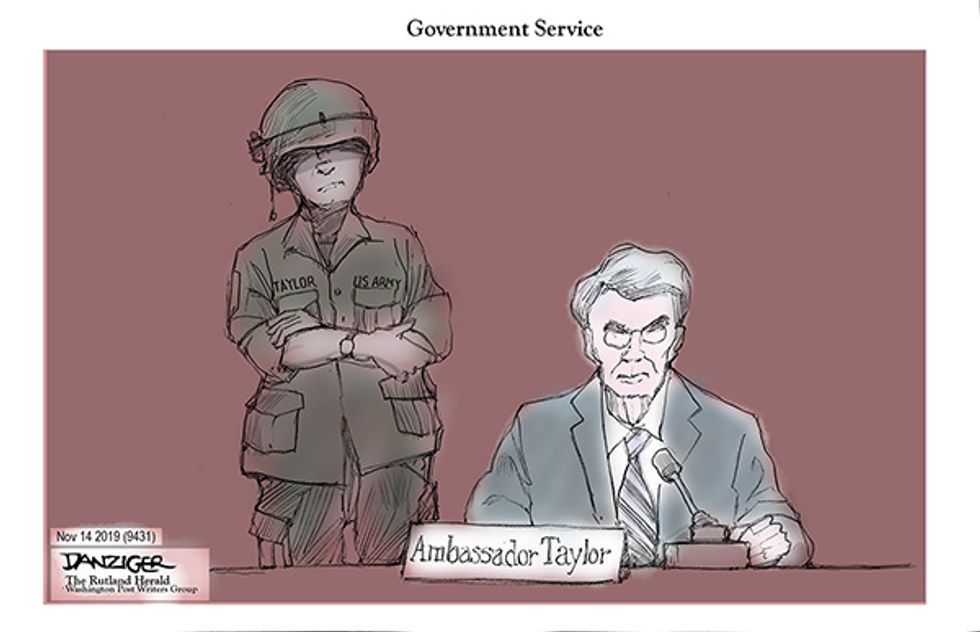

This is me remembering our history with invading much smaller countries with our huge military might:

We’re headed into another world of hurt.

Reprinted with permission from Lucian Truscott Newsletter.