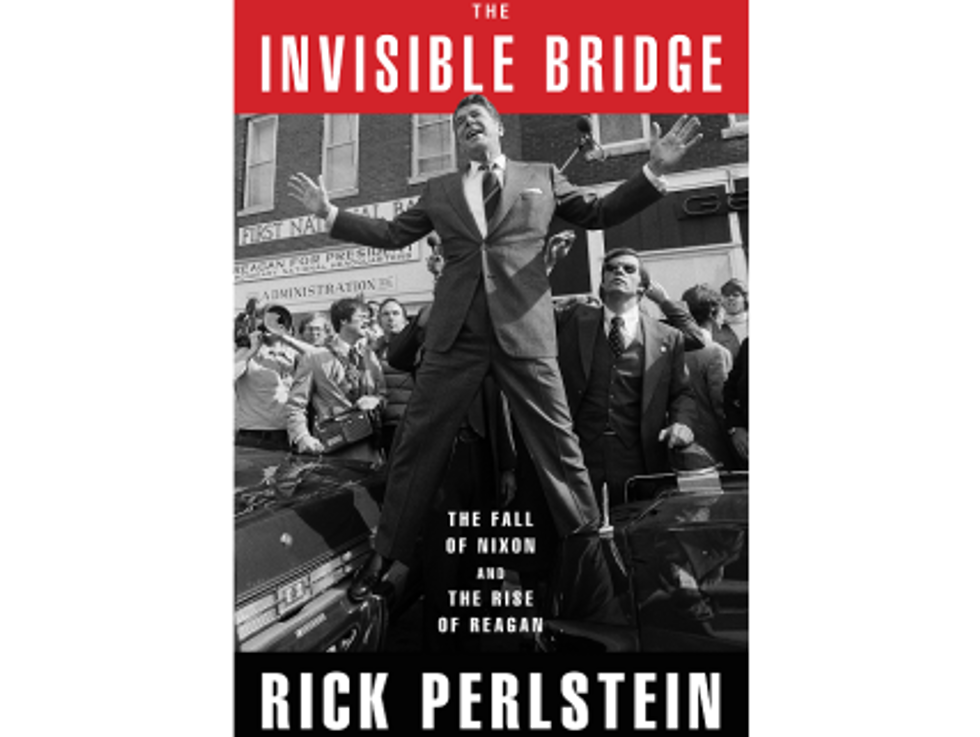

Weekend Reader: ‘The Invisible Bridge: The Fall Of Nixon And The Rise Of Reagan’

Today the Weekend Reader brings you The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan by journalist and historian Rick Perlstein. Following up on his previous book, Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America, Perlstein dives into the rise of GOP darling Ronald Reagan in the 1970s. The former actor and governor of California was an unlikely contender for the White House when he announced his candidacy against President Gerald Ford, but his political savvy eventually prevailed—Reagan’s patriotism enchanted Americans who were disheartened and battered by both Nixon’s Watergate scandal and a foundering economy. Perlstein’s historical analysis looks deeper than the 70s headlines and provides an essential and thorough understanding of Americans’ perception of politics, Ronald Reagan, and conservatism during a pivotal era.

You can pre-order the book here.

Thus arrived an unlikely development: chasing spooks became a political opportunity. Frank Church, the liberal Democratic senator from Idaho, a longtime critic of the CIA (“I will do whatever I can, as one senator,” he had said years earlier, “to bring about a full-scale congressional investigation of the CIA”) and scourge of the Vietnam War (“a monstrous immorality”)—and a presidential hopeful—maneuvered himself into the chairmanship of the new Senate Select Committee to Study Governmental Operations with Respect to Intelligence Activities. And for one of the members of the new Rockefeller commission, CBS reported, “the assignment could help keep presidential hopes alive.”

That would be Governor Ronald Reagan, a surprise pick that had Washington insiders wondering if President Ford—approval rating: 42 percent—was more worried about a nomination challenge than anyone had previously thought. The New York Times did not approve. Reagan, it reported in a February article that read like an editorial, had “missed three of the four weekly meetings of the Presidential commission investigating the Central Intelligence Agency.” He “reportedly told President Ford when he was asked to join the panel that his speaking engagements might conflict with the meetings.” His secretary promised Reagan would “catch up by reading the transcripts of the missed sessions”—though, “according to the commission staff, Mr. Reagan has not yet visited the commission headquarters, where hundreds of pages of transcripts are kept in locked files.” Instead, “During January, he gave seven ‘major addresses’ to such groups as the International Safari Club, in Las Vegas.”

Who could take seriously a lightweight like that? Though CBS still spied a possible opening for a Reagan presidential bid: “If the economy overwhelms President Ford.” Portents hinted at just that. In fact, that news was getting downright apocalyptic.

In December economists announced that the nation was officially in a recession. By January the projected annual growth rate was negative 5 percent. A Harris poll found only 11 percent of the country thought Ford was “keeping the economy healthy.” Even the Godfather of Soul got into the act: “People! People! Got to get over, before we get under,” growled James Brown in a new hit that was number four on the R&B charts: “There ain’t no funky jobs to be found. Taxes going up . . . now I drink from a paper cup. Gettin’ bad!”

On the heels of a Pentagon move to eliminate 11,600 civilian jobs at military bases, the auto industry announced 40,000 layoffs. Ford Motors cut production schedules at eleven of its twenty North American assembly plants and most of its forty-five manufacturing plants. Chrysler laid off almost 11,000 white-collar workers. American Motors idled 7,000 workers in one plant in Kenosha, Wisconsin, alone. In New Hampshire, a textile mill that had been in business since 1823 was scheduled to shutter. Maryland’s largest private employer, the four-mile-long Sparrows Point steel complex, began laying off thousands; 100,000 steel workers lost their jobs nationwide between the previous summer and the upcoming fall; in December 1974—Christmastime—185,000 blue-collar workers found themselves without work. Businesses and consumers preferred products made elsewhere: foreign car sales were up 20 percent, American cars down almost 13. The Economist said, “Capitalism is being tested everywhere. Many people believe it is dying.” It called the closing of 150 investment banks and securities dealers in the United States in recent weeks “some of the worst failures since the Great Depression.” The National Association of Home Builders called the slump in its industry “far and away the worst since the Depression.”

Since the Depression: a new household phrase.

It felt as if America did not even own itself. “Will Araby Bankrupt the World?” the January 25 Saturday Review cover asked. Rumor was that Saudis had bought up all the real estate in Beverly Hills. Arabs had bought us, yes, but they also hated us: in one page-turner selling out at airport book stores, Black Sunday, Palestinians had no trouble recruiting one of those sturdy patriotic heroes of 1973, a Vietnam prisoner of war, his brain too addled by torture to resist, to pilot an explosives-laden blimp into the Super Bowl; in another, The Gargoyle Conspiracy, Arabs assassinate the secretary of state. (Time noted jocularly that the Arab-bashing thrillers might someday no longer be published, if the Arabs bought all the publishing companies.) Meanwhile, the real-life secretary of state, in a Christmastime interview in BusinessWeek, hinted that a military strike to seize Middle East oil fields outright might be imminent. Then he left for a hat-in-hand tour of Arab capitals, as if making amends.

Gerald Ford, in his January 15 State of the Union address, was hardly more comforting: “I must say to you that the state of our Union is not good,” he said. No president had ever told the citizenry anything like that.

But Ronald Reagan as the answer? His preferred solution to the crisis—turning management of the economy even more over to private interests—didn’t sound right even to the conservative City of London gentlemen who edited the Economist. They opined that much of the blame for capitalism’s tests lay with “a concentration of money into the hands of a few big banks, even more than these giants know what to do with.”

In any event, with Ford tacking to the right, it was hard to see what room Reagan might have to maneuver. “Ford Lauded By Wall Street on Inflation,” read a headline about his speech to securities analysts who “generally applauded what they saw as President Ford’s renewed determination to tackle inflation, rather than recession, as the nation’s chief economic problem.” He gave speeches in which he said things like “We face a critical choice. . . . Shall we slide headlong into an economy whose vital decisions are made by politicians while the private sector dries up and shrivels away?” The major economic idea in his State of the Union message was a tax rebate of around one hundred dollars for the average American, which was just the sort of thing a President Reagan would be likely to propose.

“President Reagan”—that inconceivable phrase. Ronald Reagan, who was still defending Richard Nixon, and who said two weeks before Gerald Ford’s pardon that “the punishment of resignation is more than adequate for the crime.”

Ronald Reagan, who told CBS “I hope to devote my time to hitting the sawdust trail and preaching the gospel of free enterprise”—“the gospel,” like this was revealed truth or something.

This in a country where the most talked-about new bipartisan legislative proposal was soon to be Jacob Javits and Hubert Humphrey’s “Balanced Growth and Economic Planning Act,” which attempted to grow the country out of stagflation by setting up an Office of National Economic Planning to govern such heretofore unregulated parts of the economy as factory production, and which would submit six-year plans to Congress every twenty-four months. This might once have sounded like something out of the Soviet Union. But now—why not? One of Ford’s aides, who would go on to become vice chairman of Goldman Sachs, thought Ford should co-opt the idea as his own, as “a highly constructive presidential initiative.” Intellectuals devoured the arguments of sociologist Daniel Bell, in The Coming of Post-Industrial Society: A Venture in Social Forecasting, “that, today, we in America are moving away from a society based on a private-enterprise market system toward one in which the most important economic decisions will be made at the political level, in terms of consciously defined ‘goals’ and priorities.’ . . . A turn to non-capitalist modes of social thought . . . is the long-run historical tendency in Western society.”

If you enjoyed this excerpt, pre-order the full book here.

From Invisible Bridge by Rick Perlstein. Copyright © 2014 by Rick Perlstein. Reprinted by permission of Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Want more updates on great books? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!