Weekend Reader: ‘Market Madness: A Century Of Oil Panics, Crises, And Crashes’

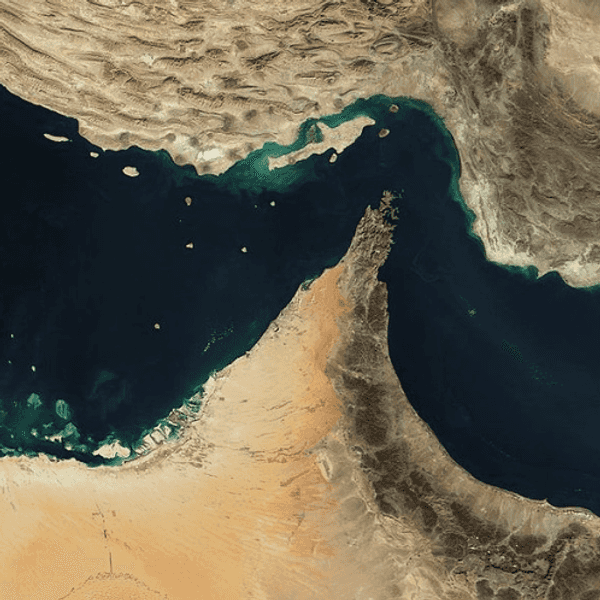

Oil not only powers the engines of industry and commerce, it also fuels anxiety, panic, and fear in the market like no other commodity can—and is responsible for some of the biggest economic upheavals of the last century.

In Market Madness: A Century of Oil Panics, Crises, and Crashes, stock analyst Blake C. Clayton tempers the craze surrounding oil exhaustion through a combination of historical investigation and sober, persuasive analysis. His book is a lucid, credible riposte to apocalyptic ravings about “peak oil.” Clayton examines how such panics have persisted through the decades, all unfounded, yet devastating to the market. Market Madness enjoins consumers, policymakers, and brokers to abstain from hysteria and remain informed about what the future of energy truly holds.

You can purchase the book here.

Awaiting the End of Oil

It is easy to scoff at Andrew Carnegie’s failed scheme to corner the world oil market by digging a pit in Pennsylvania, but the future titan of American industry was no fool. In fact, that is what makes the story remarkable: Here is one of the modern world’s great industrial minds—not exactly your average investor—with a carefully laid plan, a seemingly reasonable investment strategy, and the means to carry it out. And yet, in hindsight, his miscalculation was laughably wrong. One hundred and fifty years later, the global oil production collapse that he and his colleagues were banking on still has not struck.

What makes Carnegie’s youthful misjudgment so interesting is that he is hardly the only one over the course of American history who has confidently predicted that oil supplies would soon run out, causing prices to leap higher— quite the opposite, in fact. Pessimism about the future availability of oil is as old as the industry itself. Carnegie succumbed to it, but so have countless others, including those in several generations after him. The same prophecy of exhaustion that led him to dig the “lake of oil” is shared by many in the world today, who see humankind as doomed to suffer the negative consequences of geological stubbornness. Those who believe that the world is facing a permanent shortage of oil, or even an era of permanently higher prices, are only the latest voices in a timeless American refrain: “Oil is here today, but will be gone tomorrow,” the song goes. It is a prediction with a long pedigree.

Fast forward to the summer of 2008. Oil prices were defying gravity. To American SUV owners, the market seemed like some sort of dystopian casino, where anyone who needed to buy gasoline stood in fear of what tomorrow’s trading on the commodity exchanges would bring. It was almost so bad that you could not look away: $87 per barrel for Brent crude oil in January, $100 by February, $109 in March, then $115 the next month, followed by $129 in May. Those numbers may not sound high today (which is a troubling thought), but oil had never cost more than even $80 per barrel before 2006. And now prices were hitting $147 per barrel in July 2008.

But the ticker tape drama was not what was oddest about the market as prices ascended. It was what the experts were saying about why prices were rising. Pundits touching every corner of finance, energy, and politics— from hedge funds, investment banks, and the oil majors to OPEC ministers, the White House, and the Federal Reserve—were all being asked that question. They each had their own arguments about why prices were high and where they might be headed. Listening to them, it was clear that they frequently understood the most basic aspects of the oil market almost totally differently from each other. That was true whether the question was how much oil the world was producing, how much oil production capacity existed in the world, if oil prices would return to their previous lows, whether Wall Street was to blame for driving prices higher, and perhaps most fundamentally, whether publicly available data about the oil market could be trusted at all.

And then there was the most fundamental issue of all: Whether this was the end of the oil age—if the world was running out of cheap oil, once and for all, making $150-per-barrel oil the new normal.

Was this the beginning of the end for oil? It was not merely an academic question. Oil is central to the world economy. No other good on the planet is traded more, by market value. Transportation depends on it. Militaries require it. Economies rely on it. Yet, in the summer of 2008, the simple question of whether there was more oil or not in the ground, and if oil prices were destined to keep rising for the foreseeable future, remained an open question in newspapers and on television sets around the world.

In reality, 2008 was not the first time the world had supposedly “run out” of oil. Prophecies of an imminent end to the oil age are as old as the oil industry itself. Like the boom-and-bust pattern that has defined oil production over the entire course of its history, so too have widespread, if misguided, predictions of ever-rising prices been a recurring feature of public discussion when it comes to the future of energy. These cries seem to get louder when demand outruns supply and prices rise sharply, only to be quickly forgotten when the market swings into surplus and prices inevitably retreat. The same kinds of stories that helped to fuel the dot-com bubbles and housing crises of the last two decades also characterize the last hundred years of the oil market. Although these stories are not responsible for the zig and zag of oil prices, they can all too easily cause investors, politicians, and the public alike to grossly misunderstand what lies ahead for the world’s energy supplies.

A host of sources—books, newspapers, magazines, the Congressional Record, government-commissioned studies, and later, documentaries, television shows, and blog posts—tell the story of these cyclical fears. Whispers of an impending oil shortage can be found in Pennsylvania in the 1870s and 1880s as the region’s wells are tapped more and more aggressively. Carnegie’s “lake of oil” came about in that context. Shortage fever took hold again in World War I and the booming 1920s, as the nation’s love affair with the automobile began to take off, lifting consumption to once-unthinkable heights. The shortage narrative arose a third time in World War II and the 1950s. The thought that the country’s oil reserves, recognized by the White House as a strategic commodity essential to modern warfare, would soon be gone struck fear into the heart of Washington’s top brass. The narrative gripped the nation in the 1970s, as the oil crises of that decade appeared to many to herald the decline of the United States (and indeed of the West), which was running up against the limits to growth. Most recently during the mid-2000s, stalled output outside OPEC and a booming China catapulted oil prices higher accompanied by fervent claims that the earth’s capacity to pump more oil was running out, if not the stuff altogether.

None of these eras was exactly alike, though they share certain striking similarities. History has not repeated itself, but it has rhymed. In each of these periods, expert predictions of an imminent, irreversible shortage of oil, broadcast widely by the media, have driven the scarcity narrative. Everyday Americans heard stories about a coming day when it would be more expensive to fill their gas tanks than ever before—if they were able to fill them at all. Deep cultural or political concerns often helped fuel the amplification of these worries. Undercurrents of fear about the future of the environment—for instance, about the need to conserve the country’s natural resources or of irreversible harm being done to the landscape—often seemed to buttress the fears. So too did concerns that draining the country’s oil fields would risk subjugation to a foreign military power, a fear often reinforced by the country’s political and military elite. These narratives would hold sway in important circles for years or even a decade at a time, only to fade away, and then reappear once again a generation later. Each time, the end of the oil age appeared imminent. But in every case, a tidal wave of new oil eventually hit the market, lowering prices. The oil shortage story would disappear from the nation’s media. It was boom-and-bust writ large.

From Market Madness: A Century of Oil Panics, Crises, and Crashes by Blake C. Clayton. Copyright © 2015 by Blake C. Clayton. Reprinted by permission of Oxford University Press

If you enjoyed this excerpt, purchase the full book here.

Want more updates on great books? Sign up for our email newsletter!