By Tirdad Derakhshani, The Philadelphia Inquirer (TNS)

He created a new boogeyman worthy of the Grimm Brothers in Freddy Krueger and dragged the horror film screaming into the postmodern age with ironic, self-referential films that mocked the conventions of their own genre.

A Nightmare on Elm Street and Scream director Wes Craven, who died Sunday at 76, redefined the slasher film, adding nuance, thematic depth, and meaning to a type of film often accused of trading in mindless violence. While his friend and contemporary John Carpenter gave us straightforward chills with the nefarious actings out of a knife-wielding nemesis in Halloween, Craven enriched the slasher with social critique, as in The Hills Have Eyes. And he celebrated the act of storytelling, pushing the boundaries of popular movies in the process.

If George Romero will forever be remembered for the zombie flick and Clive Barker for imagining the landscapes of the damned, Craven will remain the man who achieved the apparently impossible: introducing the intelligent slasher.

Craven directed more than 20 features and wrote and produced a dozen more over a career spanning nearly five decades. But he began his professional life as a scholar, earning a master’s degree in philosophy and writing from Johns Hopkins University. He briefly taught literature and humanities at Westminster College and Clarkson College before dropping his first bombshell of a film in 1972 with The Last House on the Left. One of the most vicious, disturbing and effective horror films ever made, it was banned in several countries, including the United Kingdom.

Based on Ingmar Bergman’s 1960 classic, The Virgin Spring, Last House was a revenge tale about a group of hooligans who abduct, torture, and rape a pair of young hippy girls. Later, they seek shelter at a house that happens to belong to one of their victims’ parents.

A pared-down, minimalist masterpiece made for less than $90,000, Last House had the newsreel realism of Vietnam War footage, and the sobering effect of reports about the Manson Family murders.

The film was a shocking revelation in an era when horror was dominated by outsize monsters and villains, over-stylized vampires, weirdly woolly werewolves, and funky aliens from strange worlds. Craven took the gimmicks out and brought horror down to earth, to the everyday streets and lanes where the audience actually lived.

Craven’s 1977 follow-up, The Hills Have Eyes, about a suburban family targeted on a road trip by a clan of inbred savages, confirmed the director’s obsession with middle America. Presaging the work of David Lynch, Craven spent the next two decades exposing the grotesque secrets that lie hidden in the homes of the most ideal families.

Craven navigated the fairy tale world of the Grimms in his next genre-defining offering, 1984’s A Nightmare on Elm Street.

A Freudian parable for the latchkey generation about the responsibilities parents bear for their children, the gory slasher was about a monstrous, disfigured killer who taunted, tortured, and killed children in their dreams. But Freddy Krueger, who had metal talons for fingers, wasn’t just a fantasy boogeyman. His attacks had real effects on the sleeping teens’ bodies. One by one, the kids died horrific deaths.

Set in an idyllic suburban town populated by bright, shiny families with perfect lawns and late-model cars, the film was about the ugliness that infects the world of adults more obsessed with surface appearance and social acceptance than living an authentic life. As parents, they taught their offspring not to be true to themselves, but to succeed at all costs.

Behind closed doors, the adults’ lives were controlled by booze, adultery, petty jealousy, self-hatred, and explosive violence. As we eventually learn, Freddy was the ghost, shade or legacy of a real man whom the adults had killed in an act of mob violence.

A Nightmare on Elm Street spawned imitators and a slew of inferior sequels, only one of which Craven himself directed, 1994’s Wes Craven’s New Nightmare. Though it pales in comparison to the original entry, the film gave Craven a chance to introduce new style and aesthetic that would bear fruit in the Scream franchise.

Influenced by post-structuralist philosophy, New Nightmare was a self-referential parody that deployed horror tropes only to undermine them with irony. Actors from the first film appeared as themselves, including Robert Englund, who introduced the Freddy Krueger character.

If Craven began his career with an explosive dose of hyper-realism, he had his biggest box office successes with a series of postmodern puff pastries that uncomfortably grafted irony and slapstick onto the slasher.

Scream (1996) opened with a scene that had Craven shove a finger in the audience’s eye. Taking a page from Hitchcock’s Psycho, Craven introduced the film’s marquee player, Drew Barrymore, only to kill her within a few minutes. The film had characters discuss the conventions of horror movies — say, the order in which they’d be murdered — even as those conventions were unveiled before us.

The success of Scream gave Craven a chance to take a breather. And he took a brief break from scaring audiences when producer Harvey Weinstein offered him the chance to apply his skills to a mainstream drama, Music of the Heart (1999). Starring Meryl Streep, Aidan Quinn and Angela Bassett, it told the true story of an inner-city teacher in Harlem, a subject that appealed to Craven as a former teacher. The film received mixed reviews but earned Streep an Oscar nomination.

After that curious experiment, Craven returned to form with three sequels to Scream. The franchise is his most successful, having made more than $604 million to date.

Craven’s work includes several quirky gems he created while exploring other types of horror, including voodoo (The Serpent and the Rainbow), vampires (Vampire in Brooklyn, with Eddie Murphy) and werewolves (Cursed).

Yet the filmmaker will forever be identified with the slasher, which he perfected, reinvented, deconstructed and reconstructed with genius, humor, and grace throughout his career.

Now, only the imitators remain.

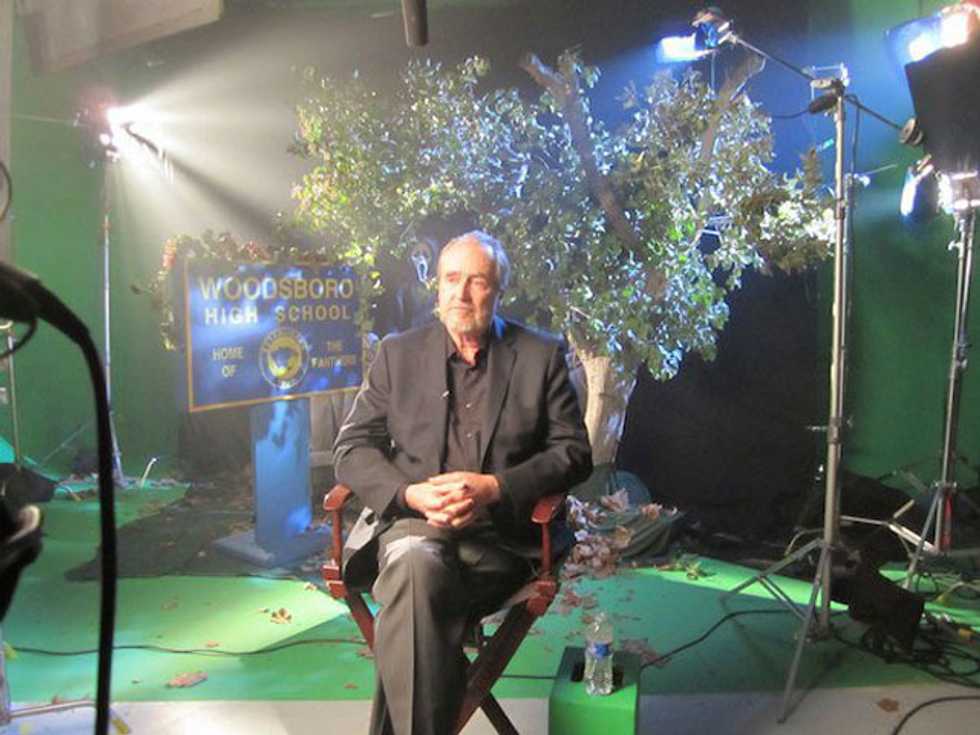

Photo: Director Wes Craven for the documentary SCREAM: The Inside Story. (Bob Bekian via )