By David Lauter, Tribune Washington Bureau

GREEN BAY, Wis. — Two years ago, politics here burned with a white-hot intensity.

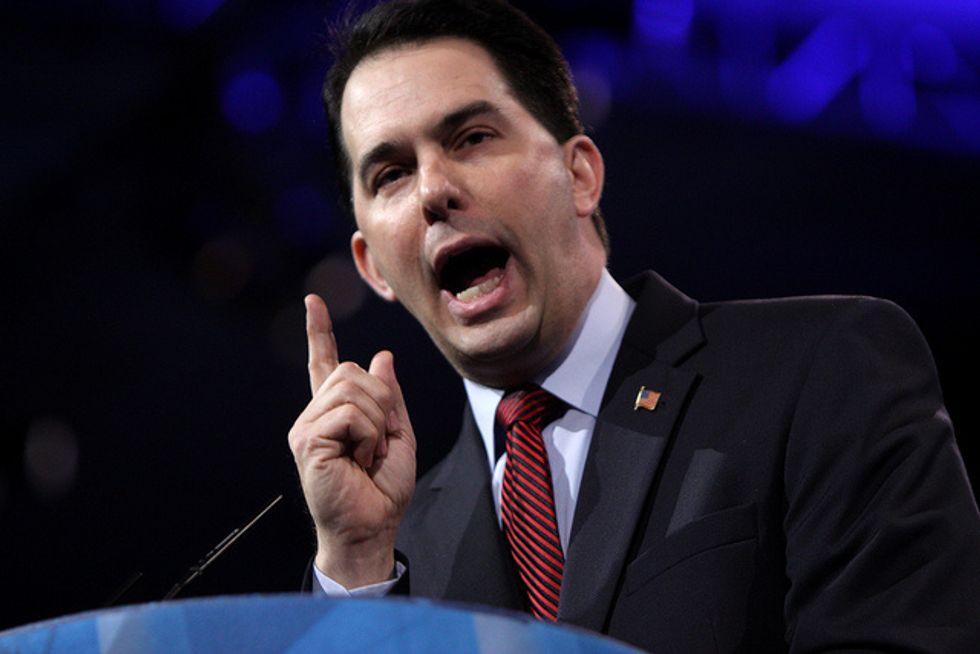

Gov. Scott Walker, a Republican elected in 2010, had pushed a bill through the Legislature eliminating most collective bargaining rights for state workers. Unions and their Democratic allies sought to recall him from office. Republicans sought to recall Democratic legislators. The battles buried any notion of voter apathy, but they split families and sundered friendships.

Nearly a third of Wisconsin voters stopped speaking to someone they knew because of political disagreements that spring, the state’s leading poll, sponsored by Marquette University Law School, found at the time.

Walker survived that fight and became a national conservative hero. Now, as he seeks a second term, the state remains one of the most politically divided in America, but the temperature has returned closer to normal.

For Democrats, that’s a strategic choice. It’s also a problem.

Having failed to defeat Walker with an all-out ideological battle in the recall, party officials felt this year that their best course was to woo the middle of the electorate.

“In a midterm election, you need someone more moderate,” said state Sen. Dave Hansen, an outspoken liberal who represents a large chunk of this blue-collar city.

Enter Mary Burke, a wealthy former executive at Trek Bicycle Corp., which her father founded, and commerce secretary in the state’s last Democratic administration.

Environmentally conscious, socially liberal, pro-business and entrepreneurial in her outlook, Burke, who easily won the nomination to challenge Walker, embodies the approach of a Democratic Party that increasingly relies on the votes of upscale, suburban, college-educated voters.

She is the sort of candidate who comes alive during a half-hour PowerPoint presentation of her economic plan, discussing the intricacies of industrial clusters and the comparative advantages of advanced transit systems.

She also jokes that her father liked to hire his children because “he didn’t have to pay them as much” — not a line likely to appeal to unionized, blue-collar workers.

She downplays ideology, arguing that her business experience would help her find the best ideas to bring more jobs to the state.

“It doesn’t matter where ideas come from, whether they’re Democratic or Republican — just whether they’re going to get results,” she says in campaign speeches.

Burke has focused intensely on the state’s weak job market, has pounded Walker for his unfulfilled promise that the state would see 250,000 new jobs in his first term, and, notably, has declined to reopen the battle over the collective bargaining law.

She insists her approach does not reflect political calculation. “It’s just who I am,” she said in an interview before a campaign appearance here. “I grew up in a household that was independent.”

That effort has achieved at least one of its goals: Burke leads Walker 53 percent to 38 percent among likely voters who describe themselves as moderates, according to the most recent Marquette poll.

But such support has not been enough to overcome Walker’s rock-solid backing from conservatives and Republicans’ significantly greater likelihood of voting this fall. And it appears to be falling short in energizing Democratic voters.

College-educated voters form a smaller share of the electorate here than in states like Colorado or Virginia, where candidates with profiles somewhat similar to Burke’s have won recent contests, and Wisconsin’s suburbs are far more conservative than those in many other states.

Overall, Walker holds a 50 percent-45 percent edge among likely voters, the Marquette poll found. Burke leads among registered voters who say they are less likely to actually cast a ballot. While women polled support Burke 54 percent to 40 percent, Walker holds a much larger edge among men: 62 percent to 34 percent.

That’s left Democrats facing a familiar midterm dilemma: how to boost turnout among urban liberals and minorities without turning off more moderate, white voters.

Walker is happy to take advantage of that problem.

“There’s been a concerted effort on behalf of our opposition to try and not be as over-the-top as they were two years ago in the recall, but you’re starting to see signs that they’re having a hard time holding that,” he said after a recent appearance at a state technical college.

Between now and Election Day, Democratic attacks will grow more strident, he predicted. “Two years ago, I think some of those tactics hurt our opposition,” he added, with a slight smile.

Wisconsin provides an extreme example of two of the big trends shaping politics nationally — partisan polarization and an electorate that leans Democratic in presidential years, but toward the Republicans in between.

The state has gone Democratic in every presidential election for a generation, starting in 1988. In midterm elections, however, turnout drops sharply in its Democratic strongholds — Milwaukee, with its large black population, and Madison, with a huge contingent of students at the state university — and the voting population takes on a reddish hue.

Wisconsin’s two U.S. senators illustrate the result. Democrat Tammy Baldwin, elected in 2012, when President Barack Obama won his second term, is one of the chamber’s most liberal members. Republican Ron Johnson, who won in the nonpresidential election in 2010, is among the most conservative. No state has two senators ideologically further apart.

Walker has benefited from the polarization even as he has contributed to it. His victory in the recall demonstrated his ability to mobilize conservative voters, and as he prepares for an expected run for his party’s presidential nomination, he argues that Republicans should offer voters clear ideological choices.

The Marquette survey and others indicate that voters disagree with him on several major issues, including increasing the minimum wage, which he opposes, and expanding the state’s Medicaid program to reach more low-income adults, which he has blocked.

But even many of those who disagree with him give Walker high marks for decisive leadership. And as the state recovers from the depths of the recession, a majority see it being on the right track, blunting Burke’s attack.

Although Wisconsin has lagged behind the nation in creating new jobs, that problem pre-dated Walker, as even Burke concedes, reflecting a state that is heavily dependent on manufacturing.

And so, in the campaign’s closing weeks, Democrats are scrambling to boost turnout among voters who may not feel inspired by Burke’s appeals to the power of entrepreneurship. Unions and abortion-rights groups plan major efforts to try to close the gap.

At a recent rally in Milwaukee, headlined by Michelle Obama — one of two events the first lady has done for Burke this month — Rep. Gwen Moore, who represents a Milwaukee-area district heavy with black and Latino voters, sought to reassure the crowd about Burke’s bona fides.

“Mary went to Harvard,” she said, but drew her values from “plain old common sense.”

In the audience, 72-year-old Edwina Matthews, a retired teacher and Democratic Party activist, said she was convinced, but wasn’t so sure about her neighbors.

“We older black people know the domino effect” that an election “can have on our lives,” she said. “But younger blacks, no.”

“I like Mary Burke,” she added, “but I think Walker may get back in.”

Photo: Gage Skidmore via Flickr