In a masterful exercise in understatement, the White House said last week that a botched Oklahoma execution was not carried out in a manner that meets the nation’s high standards for such dubious rituals. According to White House press secretary Jay Carney, “We have a fundamental standard in this country that even when the death penalty is justified, it must be carried out humanely.”

The ironies abound. When, exactly, is capital punishment “justified”? How does a civilized society carry out executions “humanely”? It’s for good reason that most of the modern world has abandoned the death penalty: It is simply not possible to be “humane” when killing another person — no matter what that person has done.

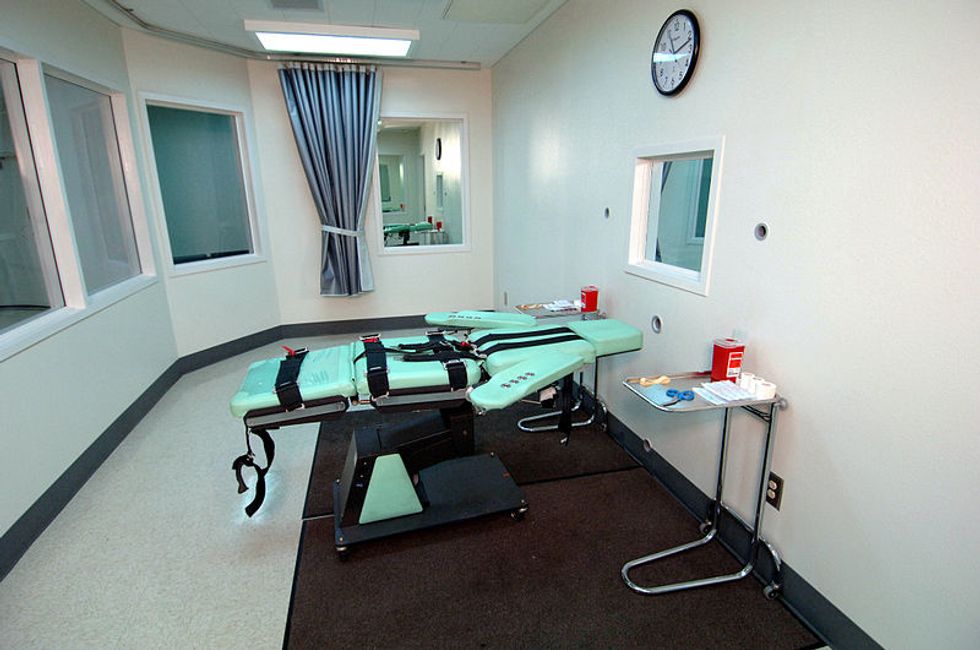

In the Oklahoma case, prison officials used an untested three-drug cocktail on April 29 to end the life of convicted murderer Clayton Lockett. But news media reports described an execution gone awry, a procedure that left Lockett grimacing, writhing and muttering. He died of a heart attack approximately 43 minutes later. Though prison officials closed the curtain to the viewing window — attempting to veil the hideous process in secrecy as it became apparent that something had gone wrong — witnesses were described as badly shaken by what they had seen.

I hold no grief for Lockett, a miserable thug convicted of shooting a young woman and burying her alive. But why does the state of Oklahoma wish to descend to the levels of barbarism that Lockett showed? How is justice accomplished when the state believes it should use the power of life and death to punish a man who believed he had that same God-like authority?

The brutality inherent in this form of punishment is just part of the problem. The other defect lies in our uncertainty about the guilt of those defendants we send to death row. A statistical study published recently in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences estimates that one in 25 death row inmates is innocent.

That means, the study notes, that several of the 1,320 defendants executed since 1977 were certainly not guilty of the crimes for which they were put to death. In killing them, then, we have been guilty of murder ourselves. We hide behind our legal processes and apparatuses — police, prosecutors, juries, judges — but we have empowered them to act on behalf of the citizens. So we are guilty all the same.

Think about it: Since 1973, 143 inmates have been exonerated and freed from death row — found not guilty of the crimes for which they were sentenced to die. It does not strain credulity to assume that some innocents were missed.

They were men you have never heard of, whose lives meant nothing to you. Many of them lived on the margins of society; some had been in and out of trouble with the law for much of their lives. Still, a society that prides itself on a pledge of equal justice for all ought to be torn apart by the notion that those men — were it not for good fortune and timely intervention — would have been wrongfully executed.

There are signs that the American public is beginning to see the injustice and inhumanity in capital punishment. Public opinion polls have shown declining support for the last two decades; while a majority of Americans — about 55 percent — still favor it, that’s down from about 78 percent in 1996, according to a 2013 Pew Research survey. Eighteen states and the District of Columbia have already banned the death penalty; governors in Colorado, Oregon and Washington state have prohibited the practice while they are in office.

Indeed, the botched execution of Lockett points to hurdles that states face in carrying out lethal injections. Professional medical societies don’t want their members involved with executions; pharmaceutical companies don’t want their names associated with the death penalty. Several states have had to resort to lesser-known “compounding pharmacies” to try to find drug cocktails to do the job.

Those states ought to get out of this ugly business altogether.

(Cynthia Tucker, winner of the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for commentary, is a visiting professor at the University of Georgia. She can be reached at cynthia@cynthiatucker.com.)

Photo via Wikimedia Commons