NPR Morning Edition aired a report this week that reeked of anti-union bias, and inadvertently promoted the Koch brothers’ agenda to reduce collective bargaining rights, which means smaller wages and benefits.

The report was rife with errors, missing facts, bollixed concepts, and a meaningless comparison used to impeach a union source.

Below I’ll detail the serious problems with reports by Lisa Autry of WKU Public Radio in Bowling Green, Kentucky, but first you should know why this matters to you no matter where you live.

A serious, very well-funded, and thoroughly documented movement to pay workers less and reduce their rights, while increasing the rights of employers, is gaining traction as more states pass laws that harm workers. A host of proposals in Congress would compound this if passed and signed into law.

News organizations help this anti-worker movement, even if they do not mean to, when they get facts wrong, lack balance, provide vagaries instead of telling details, and fail to apply time-tested reporting practices to separate fact from advocacy.

The advocates are sophisticated. They pose as “nonprofit research organizations,” but are better described as ideological marketing agencies.

There’s nothing wrong with marketing ideology, only with not being honest about what you are doing.

These tax-exempt outfits operate on the model of Madison Avenue; reinforcing instincts, hopes, and desire to stir demand for what may not be good for you or be of dubious effectiveness.

Carefully read, their reports are mostly assertions with a sprinkling of cherry-picked facts and projections, which I have found, reviewing them years later, turned out to be wrong.

Midwestern and southern states have been enacting anti-worker laws that take away collective bargaining rights, while forcing unions to represent people who do not share in the costs of collective bargaining and protecting workers in grievance proceedings. Other laws directly reduce compensation, especially pensions, although police and firefighters are generally shielded.

A key part of this strategy is creating the impression that unions are bad for workers. This goes to a problem that Presidents John Adams and James Madison feared would destroy the nation – the rise of a “business aristocracy” that would trick people whose only income was from wages into supporting policies that would be good for the business aristocrats, but bad for workers.

The NPR report was about Kentucky counties that are passing so-called “right to work” laws, a worthy topic for sure.

Early on, reporter Lisa Autry makes this untrue statement: “Democrats have rejected efforts to allow employees in unionized companies the freedom to choose whether to join a union.”

No law requires workers to join a union under a binding U.S. Supreme Court decision. Congress outlawed the “closed shop” in the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act, formally known as the Labor Management Relations Act.

Workers at firms with union contracts are only required to pay dues that cover the costs of representing them in negotiating contracts and grievance procedures.

Russell D. Lewis, the NPR Southern bureau chief who edited Autry’s report, told me he was only vaguely aware of the Taft-Hartley Act and did not recognize her error.

From an economic perspective, what so-called “right to work” laws do is allow workers to enjoy the benefits of collective bargaining and contract enforcement without sharing in the costs. This is a form of moral hazard that weakens unions and makes it likely that they will fail because of what economists call the free rider problem: Those who do not share in the costs of negotiating contracts and enforcing them enjoy the same benefits and protections as those who do.

Autry’s NPR report failed to mention a central fact – Kentucky’s highest court ruled in 1965 that cities and counties cannot adopt local collective bargaining laws. In a case that unions brought against Jesse Puckett, mayor of Shelbyville, Kentucky’s highest court ruled (emphasis added):

it is not reasonable to believe that Congress could have intended to [leave to local governments] the determination of policy in such a controversial area as that of union-security agreements. We believe Congress was willing to permit varying policies at the state level, but could not have intended to allow as many local policies as there are local political subdivisions in the nation. It is our conclusion that Congress has pre-empted from cities the field undertaken to be entered by the Shelbyville ordinance.

In reports for her local NPR station, Autry never cited this. She did, however, a report on a politician who told her that equal numbers of people believe a county-level ordinance would be legal or illegal. In another report, on whether counties have the legal authority to pass such laws, she said, “the answer depends on who you ask.”

It took me less than a minute using an Internet search engine to find the 1965 case. It was also cited in a nuanced and balanced January news report in the Louisville Courier-Journal. Even cub reporter Gina Clear of the News-Enterprise in Elizabethtown, KY provided coverage that was balanced and far better informed than Autry’s.

Did Autry fail to report the court decision because of laziness, poor judgment, or anti-union bias? I cannot give you a definitive answer because Autry and Kevin Willis, WKU’s news director, ignored my repeated requests for an interview, passing the buck to Lewis.

Strange, journalists who expect people to return their calls but do not hold themselves to that standard.

My review of several dozen Autry pieces suggests a bias against unions and workers.

Autry tends to quote anti-unionists at length, but paraphrase what union leaders say, though she did one report that explained union perspectives.

She frequently does one-sided reports using language that assumes only anti-union policies have merit, and quotes only anti-union sources. She also did a one-sided report against increasing the minimum wage.

Lewis, the NPR editor, noted that Autry quoted a United Auto Workers local official saying that Alabama and Mississippi, both with so-called “right to work” laws, have “some of the worst education, highest poverty. What happens is that as they reduce the union labor, less and less [sic] people are making a decent wage.”

But Autry followed that quote with a bizarre point to impeach the union official’s remarks: “Actually, since World War II, income and job growth have increased faster in right-to-work states.”

That might be relevant to a story about how Jim Crow laws kept, and still keep, blacks from many well-paying jobs. Or in a story about how taxpayer investments, especially in the Interstate Highways, canals, and electricity, opened the South to building factories after the war.

Autry cited no source. Lewis sent me a report by the Mackinac Center, another libertarian marketing agency. It is much more nuanced than Autry’s flat statement.

And actually, to invoke Autry’s word, what would be relevant would be current data on household incomes in states with and without laws requiring workers to pay for the benefits they get from any union that represents them.

In 2013 the median household income (half make more, half less) was $49,087 in so-called “right to work” states, but $56,746 in other states. That means in the states with diminished worker rights people have to work a full year plus eight weeks to get what their peers earn in a year.

Autry’s piece and Lewis’s editing seem to violate NPR’s ethics handbook, which says “good editors are also good prosecutors. They test, probe and challenge reporters, always with the goal of making NPR’s stories as good (and therefore as accurate) as possible.”

The handbook also says “attribute everything… When in doubt, err on the side of attributing — that is, make it very clear where we’ve gotten our information (or where the organization we give credit to has gotten its information). Every NPR reporter and editor should be able to immediately identify the source of any facts in our stories — and why we consider them credible. And every reader or listener should know where we got our information.”

In her NPR piece and a number of WKU reports, Autry quotes the Bluegrass Institute, which she describes as “a Kentucky-based think tank that advocates for smaller government.”

With just two employees, it doesn’t have much capacity to think.

What Autry neglected to report was that the Bluegrass Institute is an ad agency for Kochian ideas. It is also part of a network that is funded by corporate interests closely allied with the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC), which poses as a nonpartisan advocate for smaller government and more federalism, but is funded by corporations opposed to unions, the Koch Brothers, and their confreres. While the network says its members are independent, behind closed doors it operates like an ideological Ikea selling libertarian ideas, The New Yorker magazine reported.

Editor Lewis told me he had no idea about the Bluegrass Institute’s connections.

Lewis also indicated he was not troubled by using the term “right to work,” which is both factually inaccurate and politically loaded. Based on the evidence I call them right-to-work-for-less laws. NPR surely should explain to listeners that an abundance of official data (and economic theory) show that union workers make more than their non-union counterparts.

Autry ended her NPR piece with another falsehood: “Meanwhile, several labor unions — including some from out of state — have filed a federal lawsuit to stop Kentucky’s local right-to-work movement.”

All of the unions represent workers in the county where the lawsuit was filed, a fact anyone who read the lawsuit should know. Irwin “Buddy” Cutler, the lawyer who filed the case, noted that to have standing – the right to sue – the union would have to represent workers in the county where the dispute exists.

Lewis said he did not know that, which explains his failure to ask what strikes me as an obvious question. Beyond that, what purpose did ending on this (false) point serve?

NPR owes listeners a corrective. It also needs to balance its reports and use relevant data. More importantly, all news organizations need to be wary of “think tanks” bearing easy information.

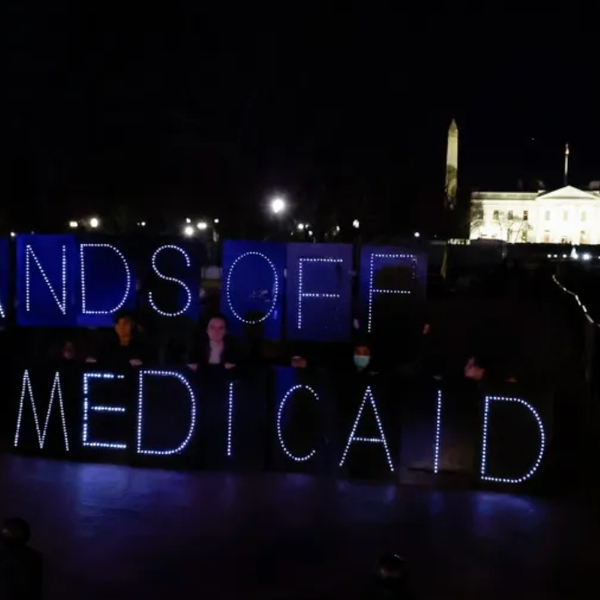

Photo: Protesters demonstrate against right-to-work laws in Madison, Wisconsin (Light Brigading via Flickr)