‘Art Of The Con’ Paints Revealing Picture Of Scammed Collectors

By Carolina A. Miranda, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

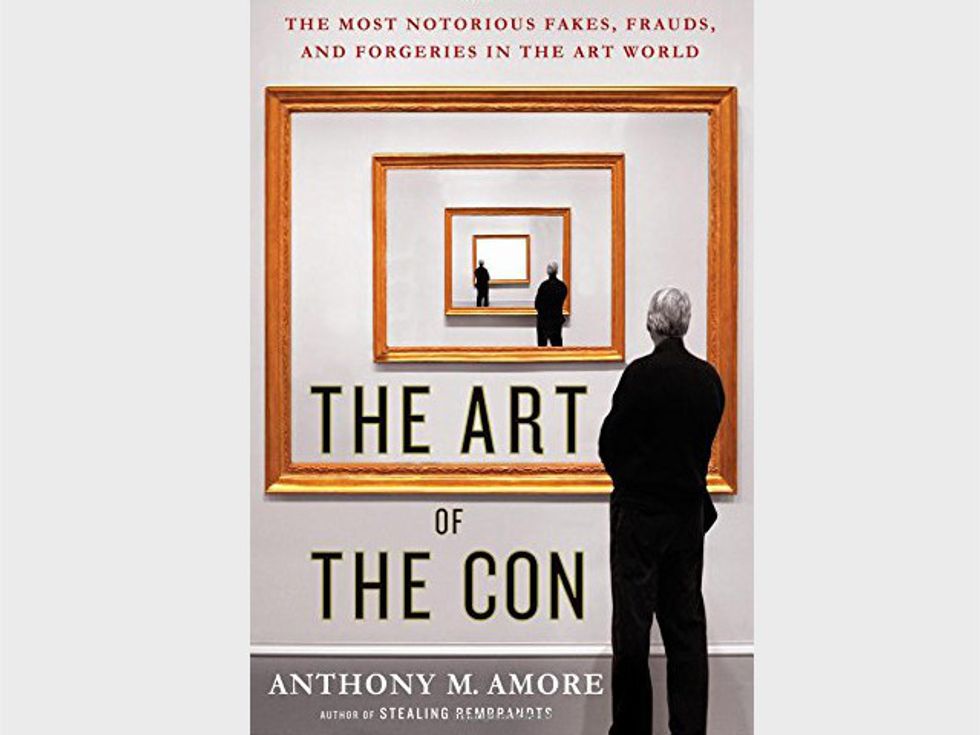

The Art of the Con: The Most Notorious Fakes, Frauds, and Forgeries in the Art World by Anthony M. Amore; Palgrave Macmillan (272 pages, $26)

___

Late last month, an art dealer named David Carter pled guilty to seven counts of fraud in a British court for passing off cheap bric-a-brac paintings he found on the Internet as originals by Alfred Wallis, an early 20th century painter known for producing marine scenes that toyed with perspective and depth. This comes just weeks after a pair of German men were accused of trying to ply a fake Alberto Giacometti sculpture to an undercover detective. The plot — it’s a thick one — involved one of the men’s 92-year-old ex-mother-in-law and an infamous Dutch forger who once kept an entire warehouse full of knock-off Giacometti bronzes.

Dip into the news on any given month and chances are you will find similar stories about art world ignominy, from the British copyist churning out oils attributed to Winston Churchill to the Manhattan dealer pushing looted Indian artifacts. There is something irresistible about that point where art and crime intersect: the money, the egos, the jet-set country club types — not to mention all the talk about provenance and brush strokes and craquelure (those cracks that form in the varnish of painting as it ages).

Anthony M. Amore would know a thing or two about the world of art swindles. For the last decade, he has served as head of security at Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, which was famously robbed in 1990 of several Rembrandts and a Vermeer. Three years ago he published, with investigative journalist Tom Mashberg, the book “Stealing Rembrandts: The Untold Story of Notorious Art Heists,” which explored the colorful history of thefts of works by the 17th century Dutch master, an activity that has involved machine guns and speed boats.

Now Amore is back with a new book that explores similar territory. The Art of the Con: The Most Notorious Fakes, Frauds, and Forgeries in the Art World looks at some of the most high-profile cases of art skulduggery from the last couple of decades. Each chapter tells the story of a single case, such as that of convicted German art counterfeiter Wolfgang Beltracchi, whose faked canvases based on the works of surrealist Max Ernst and modernist Heinrich Campendonk were so well executed that they successfully fooled even the artists’ families (as well as actor Steve Martin, who unwittingly purchased a bogus Campendonk).

Likewise, there’s the tale of West Hollywood gallerist Tatiana Khan, who claimed to be dealing works from the collection of the late real estate mogul Malcolm Forbes and who, at age 70, was busted by the FBI in a wild web of lies after selling a fake Picasso for $2 million. By the time the authorities caught up with her, she was in ill health, living in a jumbled house stuffed full of sculptures and antiques — like some sort of frayed “Miss Havisham character,” writes Amore. (She ultimately pled guilty and was sentenced to five years probation.)

In this manner, Art of the Con takes the reader through a whole spectrum of cases, from the high to the low. There is the esteemed New York art dealer who ended up in jail after deceiving a star-spangled array of high-profile clients. And there’s the case of the couple from La Canada Flintridge who produced unauthorized ink jet prints of lesser-known artists’ works for a fraud operation that extended into the world of cruise ship auctions. (Surreal and enlightening.)

While Amore recounts each of the cases efficiently from beginning to end, what’s missing is more psychology. Early on in the book, he notes that a good art con isn’t just about creating a good fake, it’s about inventing a probable narrative to go with it: “The art of art scams is in the backstory,” he writes, “not in the picture itself.”

And while he diligently conveys some of these backstories (down to the vintage family photos faked by one forger), he overlooks some big-picture questions: What makes something art? Why is art such an entrancing symbol of power? What kind of person flips a $17-million painting by Jackson Pollock as an investment? And why are so many people so willing to ignore the warning signs of a sham deal?

Art of the Con is methodically researched and reported but does little to illuminate the process of seduction that takes place when it comes to acquiring art. Buyers can do their due diligence: They can check the provenance, they can analyze the market, they can consult with the pedigreed experts. But there comes a point in many deals where acquisition is guided entirely by intangibles such as status and beauty and a desire to possess — not to mention a healthy dose of greed. Ultimately, it is in this messy gray area that a more compelling story could have been mined and told.

(c)2015 Los Angeles Times. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.