Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel Trounces Challenger In Runoff

By Bill Ruthhart and Rick Pearson, Chicago Tribune (TNS)

CHICAGO — Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel soundly defeated challenger Jesus “Chuy” Garcia on Tuesday, capturing a second term in Chicago’s first-ever runoff election and striking a note of humility by thanking voters for “a second term and a second chance.”

The win followed six weeks of a hard-fought, nationally watched second round in which Garcia tried to cast the contest as the latest proxy battle between establishment Democrats and the party’s progressive wing. Emanuel’s overwhelming financial advantage ultimately helped save the mayor as he fought for his political life.

“To all the voters, I want to thank you for putting me through my paces,” Emanuel said after springing to the stage as U2’s “Beautiful Day” blared at the plumbers union hall. “I will be a better mayor because of that. I will carry your voices, your concerns into…the mayor’s office.”

With 98 percent of the city’s precincts reporting, Emanuel had 55.7 percent of the unofficial vote to 44.3 percent for Garcia.

Emanuel congratulated the Cook County commissioner on running an “excellent campaign” and said a contest that featured an immigrant and the grandson of an immigrant showed why Chicago “is the greatest city in America.”

Garcia spoke to a raucous crowd at the UIC Forum about his journey from humble beginnings as a five-year-old who came to the U.S. from Durango, Mexico, to eventually run for mayor of the nation’s third-largest city.

“To all the little boys and girls watching: We didn’t lose today. We tried today. We fought hard for what we believe in,” Garcia said. “You don’t succeed at this or anything else unless you try. So keep trying. Keep standing up for yourselves and what you believe in.”

Emanuel portrayed the win as allowing him to continue a public life that has included senior roles for Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama and leading the 2006 Democratic takeover of the U.S. House while serving in Congress.

“While a lot of people describe Chicago in a lot of ways, all of us describe it as home. To the Second City that voted for a second term and a second chance: I have had the good fortune to serve two presidents. I have had the good fortune of being elected to Congress,” said a hoarse Emanuel, who soon after received a congratulatory call from Obama. “Being elected mayor of the city of Chicago is the greatest job I’ve ever had and the greatest job in the world. I’m humbled by the opportunity to serve you.”

Elections traditionally serve as a referendum on the officeholder, but Emanuel was effective at turning the tables on Garcia. The mayor painted the challenger as making costly promises and questioned whether Garcia had the credentials to lead a city facing enormous financial problems. The tactic also was a way to deflect attention from Emanuel’s own controversial decisions and abrasive style that marked his first term.

Left unsaid by the mayor was that his financial plans count on quick help from Springfield, an approach that has proved politically difficult in the past. That reliance on a state government bailout is likely to be even more problematic, given the state’s own financial challenges and Republican Governor Bruce Rauner’s focus on cutting aid to cities.

For an election that followed a weekend of religious holidays and fell during a week when most of the city’s schools are out on spring break, turnout approached 40 percent. That exceeded the near-record low of 34 percent in February’s first round. Four years ago, turnout was 42 percent for the open-seat contest after the retirement of former Mayor Richard M. Daley.

Emanuel suffered the national political embarrassment of being forced into the runoff after failing to eclipse 50 percent of the vote against a far lesser known field of four candidates in February. In that race, Emanuel garnered 45.6 percent, while Garcia finished second with 33.5 percent.

After the February election, Emanuel aides privately acknowledged they were not happy with the campaign’s ground game. The mayor largely relied on the ward organizations of supportive aldermen and a host of trade unions, including plumbers, pipe fitters, laborers, painters, and operating engineers as well as the hospitality workers and firefighters unions.

Garcia leaned heavily on the Chicago Teachers Union and the Service Employees International Union to turn out the vote. His goal was to win over those who voted for someone other than Emanuel in February.

But after spending weeks courting the city’s black voters, Garcia had trouble connecting well enough to make a difference. Emanuel held a lead in all of the city’s 18 black-majority wards and in all but one of the majority-white wards.

Garcia maintained a lead in 12 of the city’s 13 majority-Latino wards, the exception being the Southwest Side 13th Ward run by powerful Illinois House Speaker Michael Madigan, where Emanuel racked up a big margin.

Tuesday’s balloting came after Emanuel spent the runoff campaign doubling down on his strategy to soften his image with Chicago’s voters.

In his first commercial of the runoff, Emanuel offered an apology of sorts to voters, saying he heard their message but stopping short of saying what he did wrong.

“They say your greatest strength is also your greatest weakness. I’m living proof of that. I can rub people the wrong way or talk when I should listen. I own that,” Emanuel said in the ad.

In the closing TV spot of his campaign, Emanuel was even more direct.

“Chicago’s a great city, but we can do even better,” the mayor said in the ad, before pointing a finger at his chest. “And yeah, I hear ya. So can I.”

All told, Emanuel raised about $23.6 million compared with a little more than six million dollars for Garcia. That allowed Emanuel to get on the air quickly after the first round of balloting to define Garcia for voters before the challenger had a chance to define himself and capitalize on the momentum generated by forcing the mayor into a runoff.

About an hour after Emanuel wrapped up his victory speech, his campaign reported another $800,000 in contributions, including $300,000 from close confidant and wealthy finance executive Michael Sacks and his wife, Cari. In addition, the Emanuel-aligned Chicago Forward super political action committee reported another $200,000 from the couple Tuesday, increasing their total contribution to $1.9 million to that committee alone. The super PAC spent $2.6 million on the mayor’s race.

The mayor ran a nonstop stream of TV ads since November, more than 20 different spots that aired more than 7,000 times. For the runoff, Emanuel ran more than two thousand ads on Chicago TV stations, double Garcia’s total.

“How much did he spend? Do the math. How much per vote?” said 22nd Ward Alderman Ric Munoz, one of just two of the city’s 50 aldermen to publicly back Garcia. “With unlimited resources like that, it’s almost impossible.”

Garcia aired ads in which he criticized Emanuel for his decision to close 50 neighborhood schools and for presiding over a spike in shootings and homicides. The challenger closed his campaign with an ad that sought to convey an air of excitement around his candidacy.

“People aren’t asking for much. Just a little. For our families to be a little more secure, our streets a little safer, our schools a little better. It’s not too much to ask, but nobody’s listening,” Garcia said in the commercial. “It’s like there’s one Chicago for the powerful and another one for the rest of us. It doesn’t have to be this way. We can change Chicago.”

Garcia also received an assist from the SEIU, which aired an attack ad against Emanuel that slammed the mayor for what it contended was looking out for the city’s downtown and the wealthy at expense of the city’s neighborhoods. Chicago Forward, the Emanuel-aligned super PAC, aired attack ads against Garcia that alleged the challenger would raise taxes dramatically if elected, citing the various promises he’d made on the campaign trail.

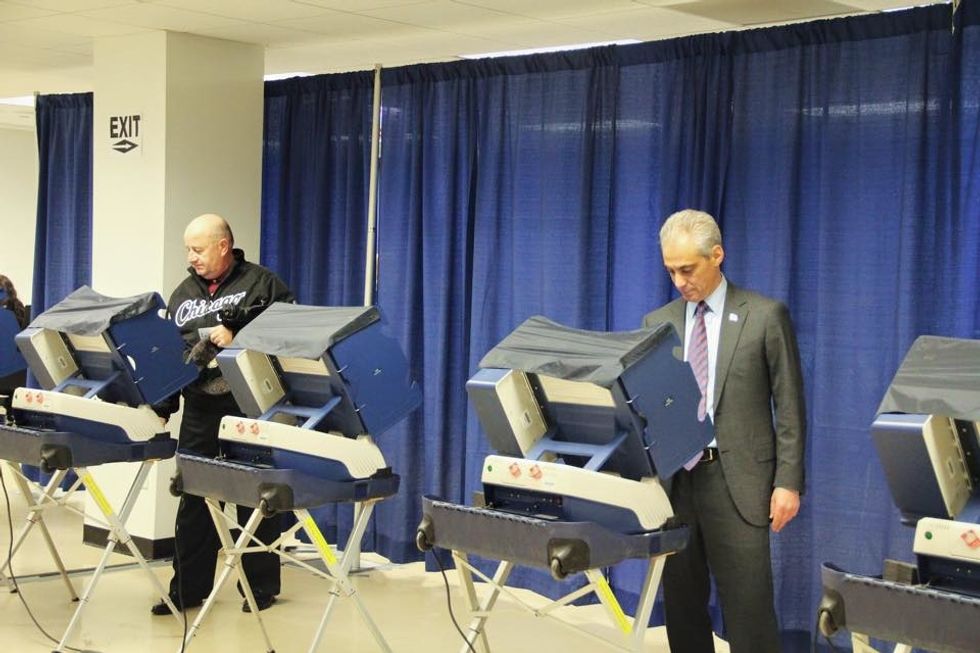

Photo: Rahm Emanuel via Facebook