A Groundswell For Sanity

Reprinted with permission from Washingtonpost.

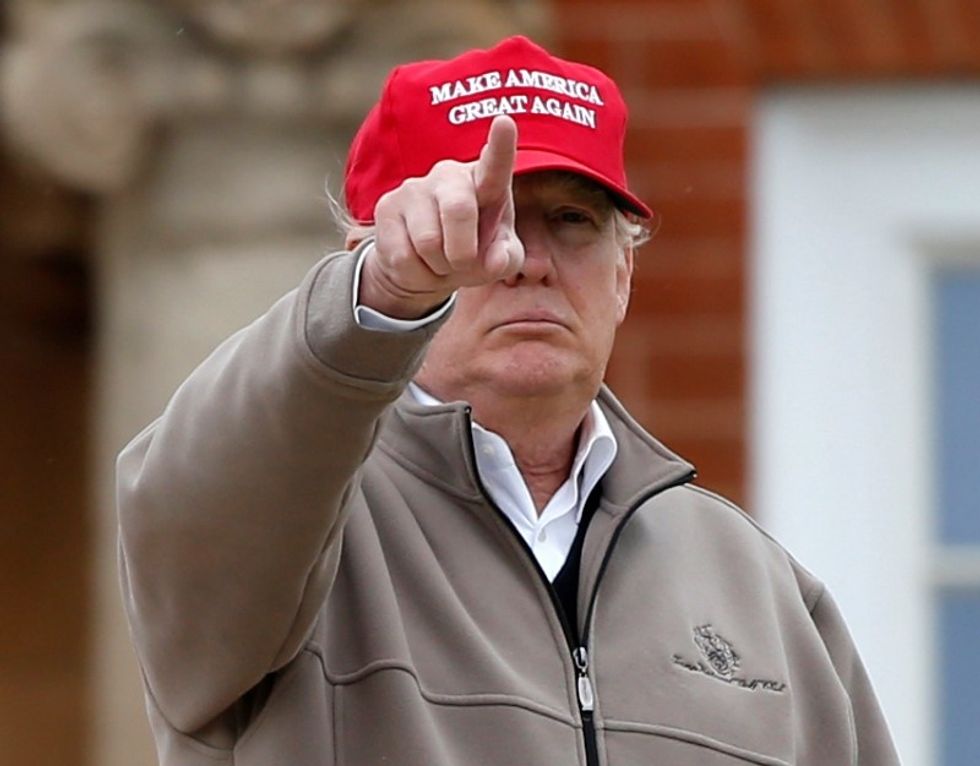

The split in American politics we may be missing is not left vs. right or pro-Trump vs. anti-Trump but normality vs. the Trump-inspired Washington circus.

If the doings in the nation’s capital seem strange when you are there, they look positively lunatic at any distance from 1600 Pennsylvania Ave.

First, the entire White House is seized by vicious infighting over its inability to tell the truth about what it knew when concerning allegations of domestic violence against a top aide. It’s remarkable how sealed off from reality this self-involved snake pit has become. President Trump has ratified the maxim that a leader gets the staff he deserves.

Combine this with the astounding disconnect between what Trump’s own intelligence officials told us on Tuesday about the threat of Russian meddling in our midterm elections and Trump’s denials and inactivity. The signal is that Trump doesn’t care what happens to the nation he leads. He is only concerned that Russian meddling taints the triumph he loves to boast about and that further investigations of it could get him into real trouble.

“If an infrastructure bill happens this year, I will eat the Internet,” says Post opinion writer Charles Lane.(The Washington Post)

Oh, yes, and there was also that payoff to the porn star.

Last are his fiscal policies. They achieve something rather astounding by contradicting both his promises of budgetary prudence and his pledges to be a pro-worker populist. What we have instead are policies that tilt toward the wealthiest, punish the least advantaged and throw the nation’s finances into chaos — an impressively perverse trifecta. And his infrastructure program is not a big bang of new construction but a whimper that effectively relies on everyone but the federal government to do the new building.

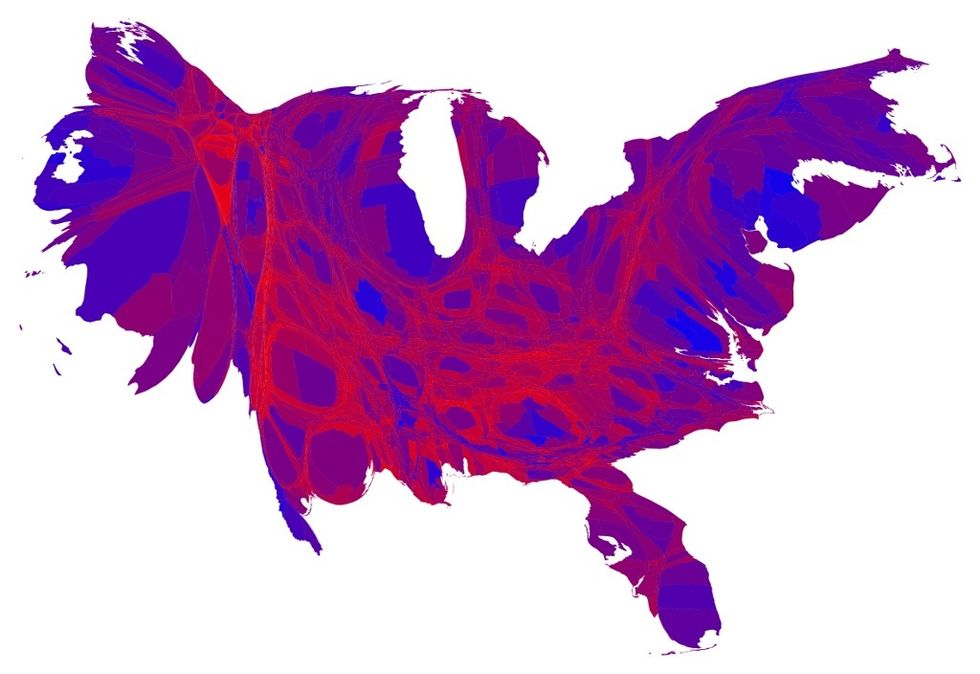

Trump’s foes reached their conclusion about his contradictions and misadventures long ago. They have responded by surging to the polls in just about every election held since 2016. The latest example was the Democrats’ pickup of a seat in the Florida House of Representatives in a special election on Tuesday. In a district that favored Trump by about five points, Democrat Margaret Good prevailed thanks to a roughly 12-point swing toward her party. It was the 36th Democratic state legislative gain since Trump’s election.

These victories are also the product of a demobilization of Trump’s own constituency. The hardest of the hardcore Trump loyalists are still likely to cast ballots this year. But he also drew support from loyal Republicans and white working-class swing voters. Many of them were not enthralled by him but couldn’t abide Hillary Clinton — or were just plain angry. It’s hard to imagine they’re overjoyed with the past 13 months.

Some members of this dispirited group overlap with a third key constituency that is underanalyzed because its ranks are not exceptionally partisan or ideological. They are citizens who ask for a basic minimum from those in charge of their government: some dignity and decorum, a focus on problem-solving, and orderliness rather than chaos. Trump and the conservatives sustaining him are completely out of line with this behavioral conservatism built on self-restraint and temperamental evenness.

It is not to romanticize the heartland to say that anyone who spends time in the Midwest runs into such solid citizens all the time. They are horrified by spousal abuse. They include small-business owners who prefer low taxes but care about schools, roads, libraries and parks. They may be critical of government, but they also expect it to do useful things. They don’t much like bragging and find an obsession with enemies unhealthy.

They are churchgoers who don’t watch TV preachers, may have doubts about this or that doctrine, and don’t tell others how religious they are. But they take from their faith and scripture that they have obligations to their communities and a duty to try as best they can to live by the standards they uphold.

They like to look up to their leaders with respect, and they feel betrayed when the powers that be give them every reason not to.

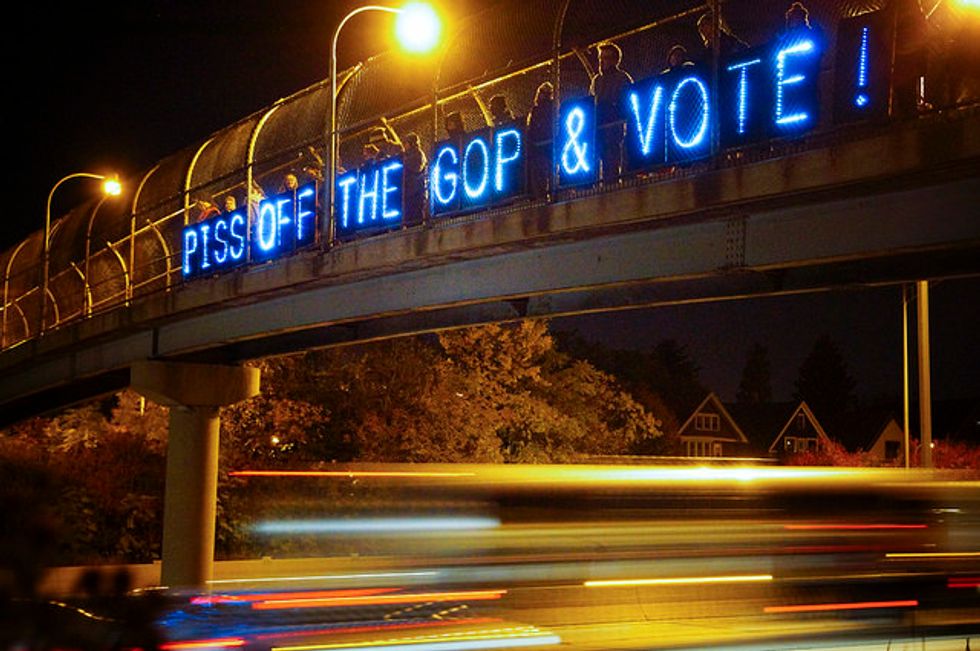

The obvious political calculation is that this fall’s elections will be decided by which side mobilizes its most ardent supporters. But here is a bet that there is also a quiet revolution of conscience in the country among those who are sick to death of the chaos they see every day on the news, a White House whose energy is devoted to stabbing internal foes in the back and a president who can’t stop thinking about himself. In the face of this, demanding simple decency is a radical and subversive act.

Read more from E.J. Dionne’s archive, follow him on Twitter or subscribe to his updates on Facebook.

Read more on this topic:

David Von Drehle: Trump’s reverse merger with the GOP is complete

Michael Gerson: Trump is vandalizing the one house he can’t own

Catherine Rampell: Trump hates deficits — unless they help rich people

Eugene Robinson: Trump tells a lot of little lies. This is the big one.

Colbie Holderness: Rob Porter is my ex-husband. Here’s what you should know about abuse.