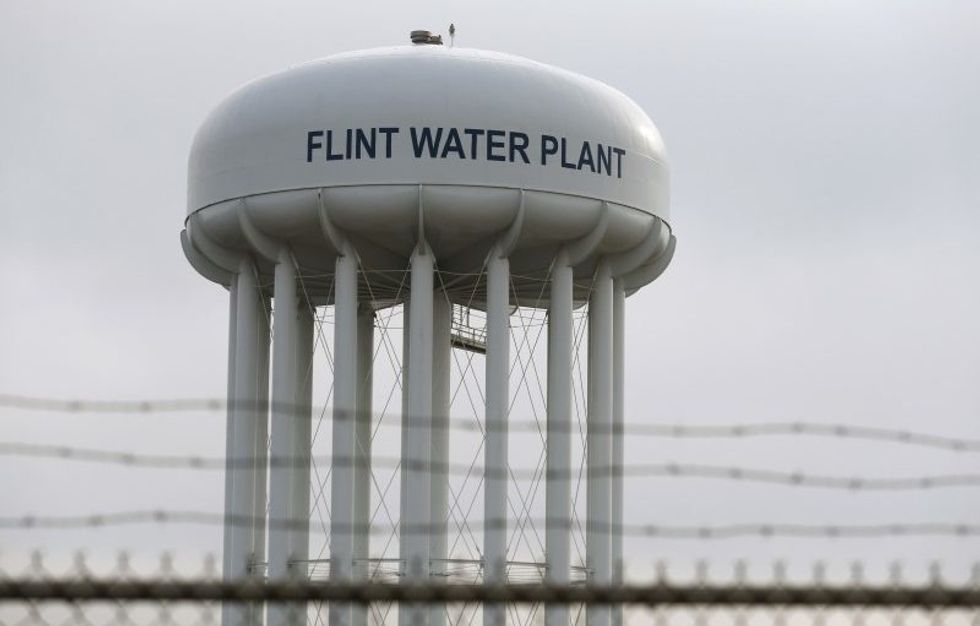

Flint, Standing Rock Prove The Impact Of Environmental Issues On Communities Of Color

Reprinted with permission from Media Matters for America.

In 2016, major environmental crises that disproportionately affect people of color — such as the Flint water crisis and the fight over the location of the Dakota Access Pipeline — were undercovered by the national media for long periods, despite being reported by local and state media early on. The national media’s failure to spotlight these environmental issues as they arise effectively shuts the people in danger out of the national conversation, resulting in delayed political action, and worsening conditions.

In early 2016, Michigan Republican Gov. Rick Snyder declared a state of emergency in the majority black city of Flint over the dangerous levels of lead in the drinking water — more than a year after concerns about the water were initially raised. While some local and state media aggressively covered the story from the beginning, national media outlets were almost universally late to the story, and even when their coverage picked up, it was often relegated to a subplot of the presidential campaign. One notable exception was MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow, who provided far more Flint coverage prior to Snyder’s state of emergency declaration than every other network combined. Flint resident Connor Coyne explained that when national media did cover the story, they failed to provide the full context of the tragedy by ignoring the many elements that triggered it. In particular, national outlets did not highlight the role of state-appointed “emergency managers” who made arbitrary decisions based on budgetary concerns, including the catastrophic decision to draw Flint’s water from the Flint River instead of Lake Huron (via the Detroit water system).

This crisis, despite media’s waning attention, continues to affect Flint residents every day, meaning serious hardships for a population that’s more than 50 percent black, with 40.1 percent living under the poverty line. Additionally, according to media reports, approximately 1,000 undocumented immigrants continued to drink poisoned water for considerably longer time than the rest of the population due in part to a lack of information about the crisis available in their language. Even after news broke, a lack of proper identification barred them from getting adequate filtration systems or bottled water.

At Standing Rock, ND, like in Flint, an ongoing environmental crisis failed to get media attention until it began to escalate beyond the people of color it disproportionately affected. Since June, Native water protectors and their allies have protested against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), an oil pipeline which would threaten to contaminate the Missouri River, the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation’s primary water source. Several tribes came together to demand that the pipeline be rejected, as it had been when the (mostly white) residents of Bismarck, ND, raised similar concerns. The tribes’ calls for another route option for the pipeline went “criminally undercovered” by the national press until September, when security forces and protesters started clashing violently.

CNN’s Brian Stelter wondered whether election coverage had crowded out stories about Standing Rock, saying, “It received sort of on-and-off attention from the national media,” and, oftentimes, coverage “seemed to fall off the national news media’s radar.” Coverage of this story was mostly driven by the social media accounts of activists on the ground, online outlets, and public media, while cable news networks combined spent less than an hour in the week between October 26 and November 3 covering the escalating violence of law enforcement against the demonstrators. Amy Goodman, a veteran journalist who consistently covered the events at Standing Rock, even at the risk of going to prison, told Al Jazeera that the lack of coverage of the issues at Standing Rock went “in lockstep with a lack of coverage of climate change. Add to it a group of people who are marginalised by the corporate media, native Americans, and you have a combination that vanishes them.”

The reality reflected by these stories is that people of color are often disproportionately affected by environmental hazards, and their stories are often disproportionately affected.

In a future in which the Environmental Protection Agency could be led by Scott Pruitt — a denier of climate science who has opposed efforts to reduce air and water pollution and combat climate change — these disparities will only get worse. More so than ever, media have a responsibility to prioritize coverage of climate crises and amplify the voices of those affected the most, which hasn’t happened in the past.

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) has reported that more than three-quarters of African-Americans live within 30 miles of a coal-fired power plant. African-Americans are also particularly at risk from climate impacts like rising sea levels, food insecurity, and heat-related deaths, and the black community is three times more likely than whites to die from asthma-related causes. Similarly, Latinos are 60 percent more likely than whites to go to the hospital for asthma and 40 percent more likely to die from asthma than white people. New Hispanic immigrants are particularly “vulnerable to changes in climate” due to “low wages, unstable work, language barriers, and inadequate housing,” all of which are “critical obstacles to managing climate risk.”

Leading environmental justice scholar Robert D. Bullard has found that “government is disproportionately slower to respond to disasters when communities of color are involved.” But media have the power to pressure governments into action with investigative journalism. According to a Poynter analysis on media’s failure to cover Flint, “a well-placed FOIA,” a “well-trained reporter covering local health or the environment,” or “an aggressive news organization” that could have “invested in independent water testing” could have been decisive in forcing authorities to act much sooner. Providing incomplete, late, and inconsistent coverage of environmental crises of this type, which disproportionately harm people of color, has real life consequences. And as Aura Bogado — who covers justice for Grist — told Media Matters, the self-reflection media must undertake is not limited to their coverage decisions; the diversity of their newsrooms may be a factor as well:

“When it comes to reporting on environmental crises, which disproportionately burden people of color, we’re somehow supposed to rely on all-white (or nearly all-white) newsrooms to report stories about communities they know very little about. That doesn’t mean that white reporters can’t properly write stories about people of color – but it’s rare.”

Media have many opportunities — and the obligation — to correct course. Media have a role to play in identifying at-risk communities, launching early reporting on environmental challenges that affect these communities, and holding local authorities accountable before crises reach Flint’s or Standing Rock’s magnitude.

While the dangers in Flint and Standing Rock eventually became major stories this year, they were not the only ones worthy of attention, and there are other environmental crises hurting communities of color that still need the support of media to amplify a harsh reality. Media could apply the lessons left by scant coverage of the Dakota Access Pipeline and Flint to empower these communities and bring attention to the many other ongoing situations of disproportionate impact that desperately need attention — and change. As Bullard suggests, every instance of environmental injustice is unique, but media coverage should be driven by the question of “how to provide equal protection to disenfranchised communities and make sure their voices are heard.”

IMAGE: Media Matters/Dayanita Ramesh