Chart: Wage Inequality Has Dramatically Increased Over Past Three Decades

A new report from the Economic Policy Institute, released Tuesday, highlights the increasingly prevalent and disparate effects of wage inequality. With a focus on same-gender wage gaps, the report demonstrates that income inequality affects all Americans, and reminds us that the implications and scope of the widening wage gap are not limited only to the poorest citizens.

The EPI notes that “since the late 1980s . . . the top has pulled away from everyone else.” As the nation’s wealthiest continued to make more money at the turn of the century, the wages of middle- and lower-class Americans remained relatively stagnant — effectively resulting in a decrease when adjusted to meet higher inflation rates — or increased at a rate slower than that by which the wages of the upper class grew.

According to the EPI, in 1979, the wages of those in the top 95th percentile were 2.2 times higher than the wages of the “typical worker,” or those considered “middle-wage earners,” at the 50th percentile. This “95/50 gap” applied to both men and women.

Over time, however, the disparity has widened.

As shown in the chart below, by 1999, men in the 95th percentile were making 2.7 times more than men in the 50th percentile. The same gap existed among women. Ten years later, in 2009, the wage gap among men had dramatically widened: The top earners were making 3.1 times more than middle-wage earners. The wage gap among women also grew wider, but not as dramatically. The top female earners made 2.8 times more than their middle-wage counterparts.

By 2013, the typical 95th percentile man’s wage was 3.3 times higher than the typical 50th percentile man’s. The same year, the typical 95th percentile woman’s wage was three times higher than the average 50th percentile woman’s wage.

The EPI’s most obvious finding is that inequality is increasing at a quicker pace among male earners than it is among female earners. But other concerns arise from the data. If men and women are disproportionately impacted by income inequality, can one assume that income inequality facilitates more general, societal inequality? Is it possible that the slower rate of income inequality experienced by women is a result of female earners making less than their male counterparts? The notion is alarming because it would prove a direct correlation between the gender pay gap, income inequality and the other forms of inequality that result directly from income inequality.

Today, the data at least prove one thing: The wage gap is widening, and both men and women are feeling it — including those who are in a better position than the nation’s lowest-wage earners.

“The enormous increase in inequality among both men and women over the last 35 years is a testament to the fact that skewed wage growth has become a core economic challenge of our time,” writes economist Heidi Shierholz in the EPI report.

High-wage inequality is, as Shierholz states, the “key wedge between a successful economy … and an unsuccessful economy,” and it is also one of the greatest threats to America’s middle class.

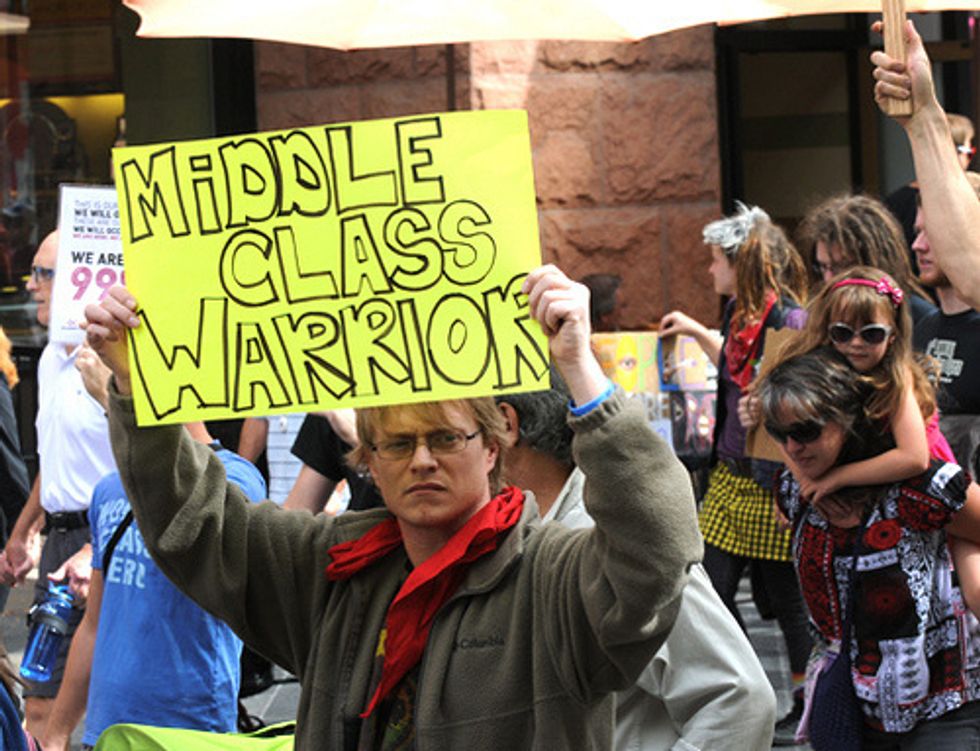

Photo: Brad_crooks via Flickr

Chart via Economic Policy Institute

Interested in the economy? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!