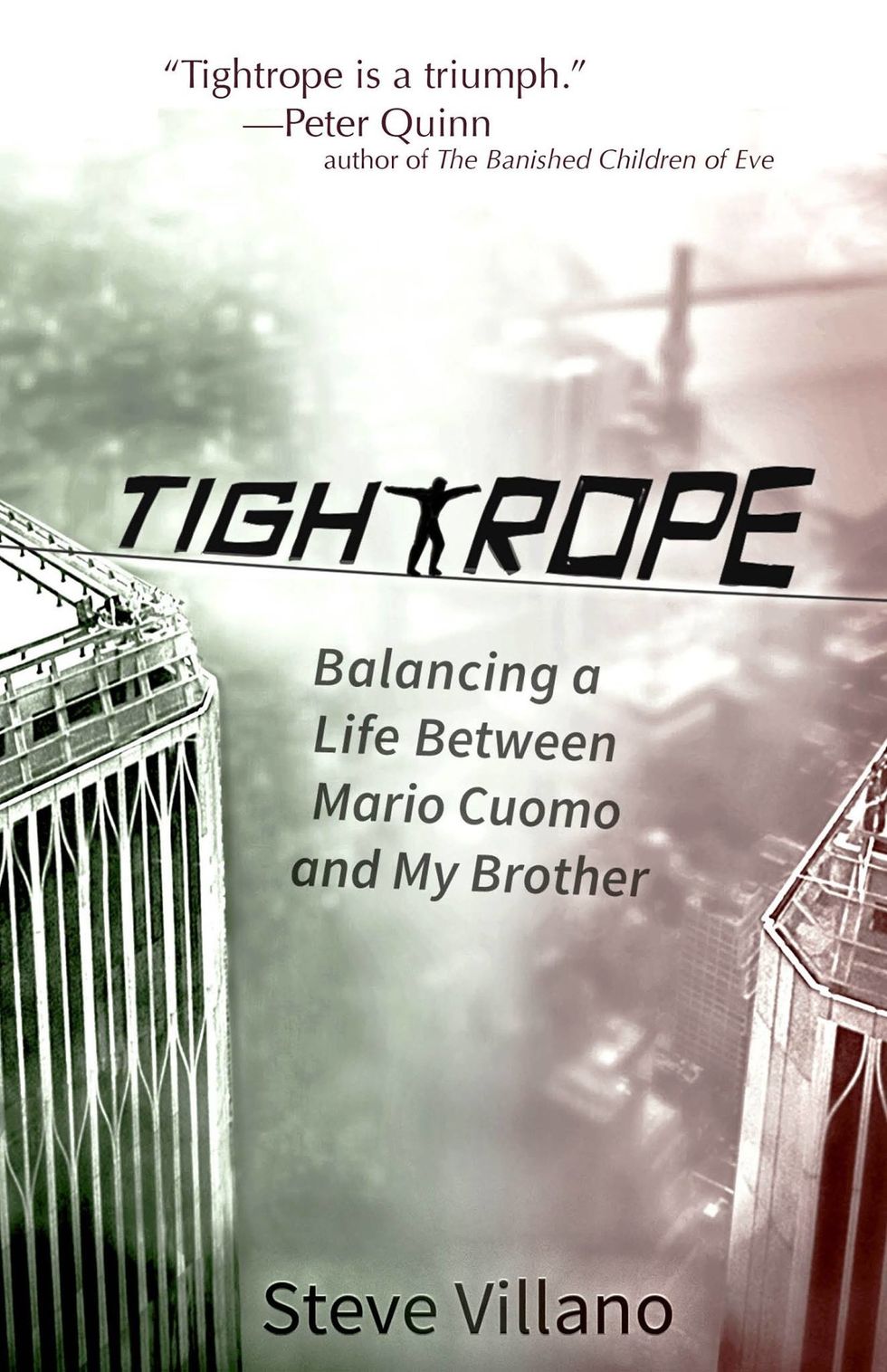

Author Steve Villano’s remarkable new book is Tightrope: Balancing A Life Between Mario Cuomo And My Brother(Heliotrope Books 2017), the true story of his life as an aide to the late New York Governor Mario M. Cuomo and the sibling of a longtime Genovese crime family associate sent to prison for tax evasion. The following is drawn from its pages:

Before all the signs and rumors that special counsel Robert Mueller’s indictments are about to start tumbling down upon Donald Trump and his associates like a ton of bricks, many of us were baffled as to how long the huge target of the criminal investigation involving the Russians could get away with his lunatic, erratic, fanatical behavior, false claims about “fake” news, and histrionic attacks on the FBI and every federal law enforcement and intelligence agency.

The clues to Trump’s bizarre behavior — and the key to the potential torrent of criminal charges against the hollow man and his mendacious minions—were right in front of us, in plain sight, and have always been Donald Trump’s role models and powerful sources of his life lessons: mobsters. Unhinged behavior like Trump’s helped keep Genovese crime family boss Vinnie “The Chin” Gigante out of jail for decades, on the theory that he was too crazy to stand trial.

That masquerade worked until members of Robert Mueller’s FBI investigative team induced Sammy “The Bull” Gravano—a man who murdered 19 people—to “flip” and provide evidence to convict John Gotti. After the Boss of the Gambino crime family was put away for life, Mueller’s men enticed the same Gravano to come out of the safety of witness protection and testify again; this time, he said that “The Chin” was totally lucid, and his insane behavior had all been an act.

Gigante, like Gotti, was convicted on Gravano’s testimony, and sentenced to life in prison, where he died. Mueller and his crack law enforcement professionals — expert in busting up criminal enterprises— were thus responsible for ending the reign of two of the most feared mobsters in the United States. Neither the Gambino nor the Genovese crime organizations (members from both of which married into my family) were ever the same again.

In Tightrope: Balancing A Life Between Mario Cuomo & My Brother, I write about the Trump family’s “ incestuous relationship with organized crime,” as the investigative reporter Wayne Barrett described it in his seminal work on the depth of Donald Trump’s lying and corruption, Trump: The Deals & the Downfall, (December, 1991, Harper Collins, NY, NY.) Trump’s ties to the Genovese, Gambino, and Scarfo mob families were of great significance to me, since my brother Michael was convicted of being a bag man for John Gotti, while I worked for Governor Mario M. Cuomo of New York.

My brother knew many of the mob guys Trump did business with, and how they joked that they could make the hair of the heir of Fred Trump’s construction business stand on end, getting whatever they wanted from him. It’s a lesson that was not lost on Russian mobsters, like Felix Sater, Trump’s partner in his SoHo hotel, and a number of his wealthy, well-connected oligarch friends. Nor was it a lesson ever ignored by Mueller and his top team of law enforcement officials. It’s also a lesson that came straight out of New York’s construction industry, where the Trumps made their money.

“I’ve never dealt with an industry that has more pervasive corruption than the construction industry,” James F. McNamara, director of former New York City Mayor Edward I. Koch’s Office of Construction Industry Relations told the New York Times in April 1982.

“When I say corruption I’m using a very broad term. Some of it is labor racketeering. Some of it is political influence. Some of it is bid-rigging; some, extortion,” said McNamara.

In an extensive story detailing the mob’s influence over New York’ss construction industry, the Times reported:

“Organized crime figures have infiltrated many important construction unions, from truck drivers to carpenters to blasters. Sixteen of thirty-one union locals in the city that represent laborers, the backbone of any construction job, are described by law enforcement authorities as being under influence of organized crime.”

Many builders and developers throughout the New York metropolitan area, including the Trump Organization, considered it part of the cost of operating in the construction business, and paid whatever extra charges were exacted through organized crime’s control of the cement and drywall industries, or other aspects of the trades.

In Trump: The Deals and the Downfall, Barrett wrote that Donald Trump met with Genovese crime family boss Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno in the apartment of attorney Roy Cohn in 1983. Cohn, hired by Trump ten years earlier, when the Trump Organization was sued by the federal government for racially discriminatory practices in housing, represented Trump as well as Salerno. The meeting between Trump and the Genovese boss occurred only a year after the New York Times had detailed organized crime’s stranglehold on New York’s construction industry, denying Trump any alibi that he did not know with whom he was meeting. Salerno, along with then-Gambino crime family boss Paul Castellano, tightly controlled the city’s concrete industry through their company, S & A Concrete. Cohn’s client list— built since he moved to New York from Washington, DC in the mid-1950s, following his work as chief counsel to Senator Joseph McCarthy (R-WI) —included celebrities, the Studio 54 club, Salerno, Donald Trump and, later, John Gotti.

Barrett, who died the day before Trump was inaugurated as President of the United States, documented that Cohn also represented Trump in meetings with another key New York construction industry player during the 1980’s, convicted labor racketeer John Cody, who was another former associate of my brother Michael.

Cody, at the peak of his power in the mid-1970s through 1982, when he was dealing with Cohn on Trump’s behalf, was no small operator. As President of Teamster Local 282, Cody controlled 4,000 drivers of delivery trucks in New York City and Long Island. He had the power to bring to a grinding halt the $2.5 billion construction industry, which employed 70,000 people. He could shut down any construction project in New York, including Trump Tower, by pulling out his drivers. Cody told Barrett: “Donald liked to deal with me through Roy Cohn.” Barrett reported that Trump did, however, have to deal directly with John Cody’s girlfriend, Vernia Hixon, to whom Trump gave a sweetheart deal for several apartments, one floor beneath his own penthouse in Trump Tower.

Despite his posturing as a New York power player, Trump cowered in front of John Cody, behaving more like a bagman, than a big man. As recently as last October, Cody’s son Michael told Christopher Dickey and Michael Daly of The Daily Beast how Donald gave Cody whatever he wanted: “Trump was a guy who would talk tough, but as soon as you confronted him, he would cry like a little girl. He was all talk, no action.”

That’s exactly the opposite of what Trump was telling Billy Bush about how he mistreated women on the now infamous Access Hollywood tape, released the week before Michael Cody’s interview in The Daily Beast and distracting most of the media from Trump’s crime family connections — which went all the way back to his father’s business partnership with Genovese crime family capo Willie Tomasello in the 1950’s. Both Fred Trump and Tomasello were hauled before a Senate committee and questioned about misuse of federal housing funds.

John Cody made sure Trump took good care of his special friend Verina Hixon, who now lived directly under Trump’s penthouse. The mobster funneled some $500,000 to Hixon for renovations of her apartments, while he was in jail for racketeering and income tax evasion. When Trump balked at fulfilling some of his promises to Cody’s girlfriend, Barrett reported that “Cody and Hixon cornered him in a nearby bar and got his agreement.”

“Anything for you, John,” was Hixon’s recollection of Trump’s comments to John Cody. “Anything for you.”

Trump was so terrified of crossing Cody that at one point, when Cody called Trump from prison to complain about construction problems on Hixon’s apartments, Barrett reported that “Trump greeted him nervously on the phone. “Where are you?” Trump asked. “Downstairs?”

“My father walked all over Trump.” Michael Cody told The Daily Beast. “Anytime Trump didn’t do what he was told, my father would shut down his job for the day. No deliveries. 400 guys sittin’ around.”

To John Cody and his colleagues, Donald Trump was just another puffed-up pasty patsy, who did whatever the mob guys asked.

Indicted by a Brooklyn grand jury on charges of racketeering, extortion, and tax evasion, John Cody was sentenced to five years in prison at the end of 1982. His sentencing judge, Jacob Mishler, was the same federal judge who would sentence my brother Michael to federal prison six years after Cody’s conviction. With Cody’s ability to wield such vast economic power and choke off Trump’s flow of cash, there was little wonder that Donald Trump asked Roy Cohn to meet with Cody to keep him happy. They were in business with these guys. They had buildings to complete, and fortunes to make. Cooperating with the FBI or federal and state law enforcement officials to clean up the construction trades industry was not in Donald Trump’s self-interest. Making money was.

“There are no heroes in this industry in terms of helping law enforcement officers,” Jim McNamara told the Times. Many observers believe that Trump, although he holds the nation’s highest elected office, behaves the same way today toward the Russian mob and its international criminal empire. See no evil, speak no evil—especially if your business is dependent upon the mobsters under investigation.

There is something eerily familiar about the attacks on the FBI by Trump and his lackeys at Fox News and in Congress. They sound exactly like my brother did, when he was sentenced to prison as a bagman for John Gotti who had never paid income taxes on the illicit money he collected for the crime boss. They sound like my brother’s former Gambino family associates with their bitter attacks on the “Feds” and the “fuckin’ gov’ment.” They all cursed the government and the FBI more intensely as the charges against them became more real, and their prison sentences became a certainty. My brother continued to curse the FBI and the “fuckin’ gov’ment” after he got out of prison–sent there because of solid FBI evidence against him.

Trump was, and still is, a punk-wannabe among punks: an amoral actor doing business with amoral peers. As John Cody’s son observed, and my brother’s friends demonstrated, they had zero respect for Trump. They knew they could squeeze him for as much as they wanted, since all that mattered to Trump was money. That’s a language understood very well by organized crime—whatever dialect is spoken by the Gambino, Genovese, Scarfo or Russian criminal enterprises. It’s also a way of life that Robert Mueller has developed great expertise—and extraordinary results—in holding accountable to the law.

Steve Villano is a journalist, film producer, educator, and consultant who worked as a speechwriter for New York Gov. Mario M. Cuomo and headed his New York City press office. He now lives in northern California.