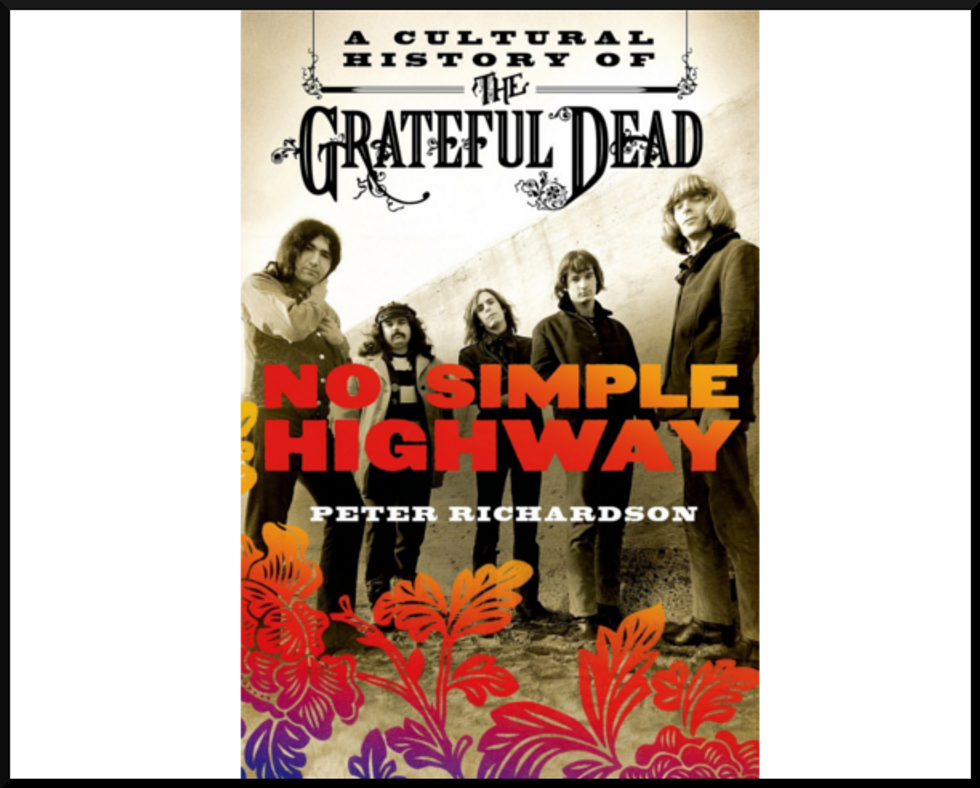

Released on the 50th anniversary of the founding of the Grateful Dead, No Simple Highway: A Cultural History of the Grateful Dead is a comprehensive history of the California rock band. Author (and National Memocontributor) Peter Richardson’s new book is a passionate and canny exploration of the group’s impact and an assessment of their legacy as “one of the counterculture’s most distinctive and durable institutions.”

As the following passage makes clear, Richardson places the Grateful Dead in a larger social context, treating the band — and its fervently loyal fans — not as curiosities on the fringes of American culture, but inextricably linked with it, as an influence on and reflection of the strange, turbulent decades in which they reigned.

You can purchase the book here.

Grateful Dead lead guitarist Jerry Garcia turned out to be an unwilling conscript in President Ronald Reagan’s drug war. By January 1985, Garcia’s drug use was so disabling that band manager Jon McIntire arranged an intervention. Garcia agreed to receive treatment, but while driving to the rehabilitation center in Oakland, he stopped in Golden Gate Park to finish off his drug supply. A police officer noticed the car was unregistered, approached Garcia’s parked BMW, and found Garcia trying to hide his stash of heroin and cocaine. Garcia’s lawyer argued that he should be sent to counseling sessions, which he attended with Grace Slick. Garcia continued to use drugs, and his health declined alarmingly. His weight ballooned to 300 pounds, and edema swelled his ankles to the point that his trousers needed to be cut. He began to diet and exercise, but the real wakeup call arrived with his 1986 coma.

Garcia’s arrest was a trifle in the drug war, but Reagan’s vision was, among other things, a repudiation of the Dead’s larger project. This much was clear to Ken Kesey. “The war is not on drugs, the war is on consciousness,” he told Paul Krassner. “Nobody has the right to come in and mess with your inside. They don’t have any right tell me what to do inside my head, any more than they have any right to tell women what to do inside their bodies. What’s inside is ours, and we’ve got a right to fight for it.” But the war on drugs was only part of the tension between Reagan’s vision and the Dead’s. What Dennis McNally called the Dead Head culture’s “hedonistic poverty” was also a rejection of Reagan’s cultural politics, just as Jack Kerouac’s “barbaric yawp” (a phrase Time magazine borrowed from Walt Whitman) and Allen Ginsberg’s howl responded to the age of Eisenhower.

In some ways, too, the Dead community’s response to Reagan was a skirmish over who would control the symbols of the American frontier. The Dead had moved on from their High Cowboy period, but their image was linked firmly to their western provenance and repertoire. Meanwhile, the Reagan team skillfully presented him as a man of the American West: riding horses, clearing brush on his ranch, and appearing on the cover of Time magazine in a cowboy hat. As an actor, Reagan had appeared in many westerns and television’s Death Valley Days. But even in private, Reagan adopted a distinctly western register. One Secret Service agent noted that Reagan sunbathed at his pool with a reflector every day at 2 p.m., no matter how busy his staff was. “That might seem like a vain, sissy thing to do,” the agent said, “but Reagan had this cowboy way of describing it. He said he was getting ‘a coat of tan.’”

Even President Reagan’s grooming habits contrasted sharply with the Dead’s. Although Reagan was three decades older than the grizzled Garcia, he had no touches of grey at all. According to Nancy Reagan’s unofficial biographer, the Clairol company paid a celebrity hairdresser $20,000 per week to fly to Washington and color her hair; while he was there, he also touched up President Reagan’s grey roots. To the end, however, the Reagan team denied the charge. “He never dyed his hair,” White House deputy chief of staff Michael Deaver claimed. “He had that wet look, and when I finally got the Brylcreem away from him, people stopped writing about him dying his hair.”

The Dead didn’t orchestrate a response to Reagan, but in the summer 1984 issue of The Golden Road, a Grateful Dead fanzine, Blair Jackson and Regan McMahon exhorted Dead Heads to register and vote against the incumbent. “Dead Heads have a reputation of being apolitical,” the couple wrote, “and there’s no question that many of you have taken your cue on the issue from members of the band, who have professed their utter contempt for the political process through the years.” Even so, the couple maintained, it was important to note that Reagan was dangerous, and that his policies would have “two great superpowers clawing at each as they never have before.” After noting Walter Mondale’s commitments to a nuclear freeze, the environment, and the Equal Rights Amendment, they directly addressed the Dead community’s resistance to electoral politics. “Voting doesn’t make you any less cool, nor does it mean you’re endorsing a political system you think is completely out of touch with the people,” they wrote. “Think for a second how Reagan has changed America already. This could well be the most important election of your lifetime.” They closed with an apology if their “political rap” offended anyone’s sensibilities and offered to publish other viewpoints in the subsequent issue.

By the time that piece appeared, President Reagan’s reelection campaign was in high gear. One of its television advertisements declared that it was “morning again in America.” But lyricist Robert Hunter’s first verse of “Touch of Grey” found little to celebrate in that daybreak.

Dawn is breaking everywhere

Light a candle, curse the glare

Draw the curtain, I don’t care ‘cause

It’s all right.

Garcia contributed the second line, which echoed Adlai Stevenson’s 1962 comment about Eleanor Roosevelt, who would rather “light a candle than curse the darkness.” But for Hunter’s world-weary speaker, who resembles Garcia during the darkest days of his addiction, the harsh morning light is as bothersome as the unnamed critic.

I see you’ve got your list out

Say your piece and get out

Yes, I get the gist of it

But it’s all right.

The speaker then refracts another bit of sunny optimism through the prism of jaded middle age.

Sorry that you feel that way

The only thing there is to say

Every silver lining’s got a

Touch of grey.

The utopian exuberance of the 1960s is nowhere in sight; instead, the speaker embraces the more modest goal of trying “to keep a little grace.” But even that is a challenge, as the next verses make clear.

I know the rent is in arrears

The dog has not been fed in years

It’s even worse than it appears

But it’s all right.

The cow is giving kerosene

Kid can’t read at seventeen

The words he knows are all obscene

But it’s all right.

In the face of economic hardship, environmental catastrophe, and educational failure, the speaker’s assurances that all is well only highlight the problems. But instead of surrendering to this dystopian scene, he promises to endure: “I will get by/I will survive.” That vaunt was a far cry from the Dead’s utopian ideals, but a simple pronoun change in the final chorus (“We will get by/We will survive”) transformed the song into an anthem. Every Dead Head knew there was a world of difference between I and we, especially during hard times. After Garcia recovered, the Dead performed in Oakland, and that message resonated powerfully with the crowd. As Garcia swung into the final chorus, Joel Selvin wrote in his San Francisco Chronicle review, “the ecstatic convocation of Dead Heads assembled Monday at the Oakland Coliseum Arena went wild with cheers.” The most cherished ideal of all, community, would survive Ronald Reagan, scourge of the hippies.

If you enjoyed this excerpt, purchase the full book here.

Excerpt from No Simple Highway: A Cultural History of the Grateful Dead by Peter Richardson. Copyright © 2014 Peter Richardson and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.

Want more updates on great books? Sign up for our daily email newsletter here!