By Gary Ferguson, Los Angeles Times

Fifty years ago Wednesday, President Lyndon B. Johnson strolled out to the Rose Garden, pressed a fountain pen between the fingers of his hefty right hand and signed into law the highest level of protection ever afforded the American landscape. “If future generations are to remember us with gratitude rather than contempt,” Johnson said later, “we must leave them something more than the miracles of technology. We must leave them a glimpse of the world as it was in the beginning.”

On that day, America gained a wilderness preservation system. Initially containing some nine million acres of wildlands, the system now protects more than 109 million acres from California to Alaska, New Mexico to Montana, Florida to New Jersey; every acre afforded the simple right to unfold unshackled by human inventions or appetites.

Johnson’s enthusiasm was in part a nod to the fact that in 1964, nature was on the run. We were by then well on our way to spreading more than a billion pounds of DDT on the American landscape. Rampant clear-cutting was happening in Oregon, Washington, Idaho and Northern California, including the decimation of many of the last privately held sequoia groves. Wild rivers were dammed. Rural states still offered government-sponsored bounties on a wide range of “bad” animals: mountain lions and coyotes, wolves and weasels, hawks and owls.

Even so, for many Americans, wild landscapes were still a major means both of celebrating the roots of our nation’s past and for defining the nature of our generosity to future generations. Across our history, periods of environmental abuse have tended to lead to fierce, highly patriotic indignation. Which is a big part of why the Wilderness Act became law with such a stunning level of consensus, passing unanimously in the Senate and with just a single dissenting vote in the House. Arguably, if the Wilderness Act does nothing more today than remind environmentalists of the patriotic power of conservation, it would be doing a lot.

But in fact wilderness does much more. Ecological economists J.B. Loomis and Robert Richardson have estimated wilderness preserves in the Lower 48 states are providing air and water filtering, carbon storage and climate regulation services worth more than $3 billion annually. In addition, wilderness use supports some 24,000 jobs, and is part of an outdoor recreation industry that sees roughly $650 million each year in consumer spending.

But beyond all that, the wilderness preservation system forms an invaluable set of base lines for showing us what healthy, natural systems look like. On the other hand, these base lines allow scientists to gain the knowledge needed to restore damage already done, including rehabilitating salmon fisheries in the Northwest, reclaiming toxic mine sites in California and the Rockies, and stemming dwindling songbird populations in New England.

At the same time, wilderness areas teach us the fundamental needs of natural systems in the face of climate change.

This latter benefit will only become more important in decades to come. Taking full advantage of it, however, will require two things: First, given that some species can’t survive in the face of the rapidly shifting habitats that climate change induces, we’ll need to expand the size of some of our current wilderness preserves.

Yet even if that happens — and the political climate today is hardly friendly to such notions — many species simply won’t be able to migrate quickly enough from their current habitats to more suitable ground. Unless wilderness managers assist in those migrations, actually moving or planting threatened species to more appropriate habitats, those species will become regionally extinct.

And this is where things get really sticky. Although the current Wilderness Act allows great flexibility — providing for all sorts of special actions so long as the original intentions of the act are honored — it can be argued that relocating species to areas where historically they never occurred is prohibited by the law.

Unquestionably, in the coming years the courts will hear a variety of challenges to the idea of wilderness managers using these sorts of tools. On the one hand, we can hardly fault those who object. As ecologist Frank Egler pointed out more than 30 years ago, “Ecosystems are not only more complex than we think. They’re more complex than we can think.” Time and again we’ve found out the hard way that just when we thought we were being helpful, we were actually causing harm.

With this in mind, even if the courts do grant increased power to wilderness managers to do things like assist migration, it seems prudent to allow some wilderness preserves to continue under the more traditional “hands-off” policy. The challenge will be knowing what to do, where.

This 50th anniversary of the Wilderness Act finds us facing something unimaginable in 1964: Today, no landscape on Earth is free of the effects of human-caused climate change. If wilderness is to continue to be characterized by healthy watersheds and vigorous biodiversity, some of its provisions will have to be re-interpreted. Only then can we hope to minimize the enormous climate changes we’ve unwittingly unleashed.

The wilderness system was fashioned both from our notions of non-human life and untamed landscapes having the simple right to exist, as well as from a desire to pass along these natural wonders to future generations. If we’re to honor those admirable impulses, we’ll have little choice but to use every thoughtful, well-considered tool at our disposal.

Gary Ferguson’s latest book is The Carry Home , which will be published in November. He wrote this for the Los Angeles Times.

, which will be published in November. He wrote this for the Los Angeles Times.

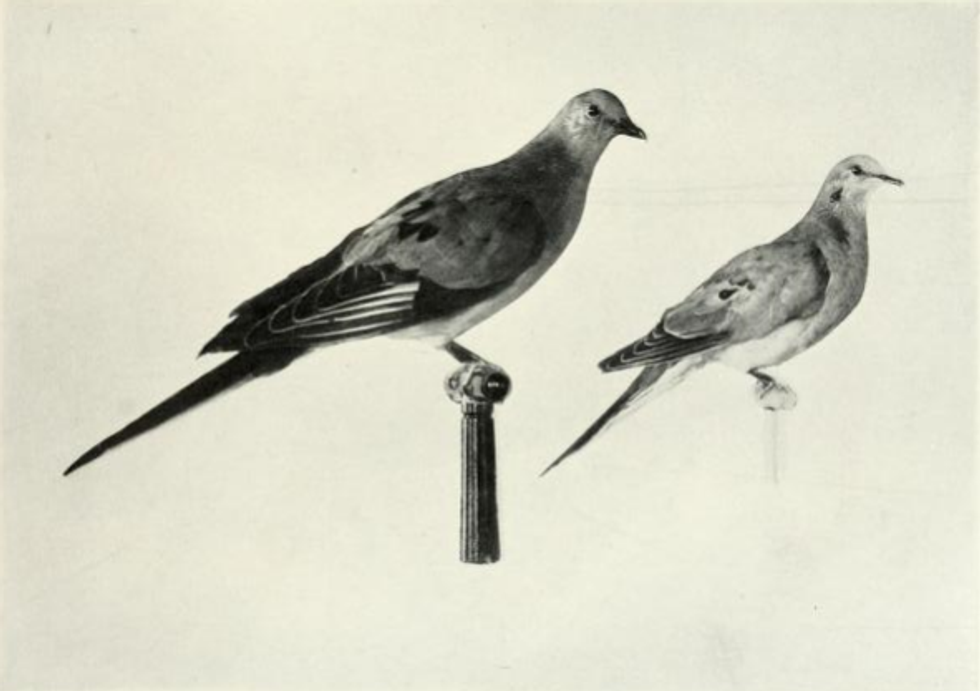

Photo: Heatkernel via Wikimedia Commons

Want more environmental news and analysis? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!