Here in the United States of America, we’re not supposed to have political show trials. People should be put at risk of felony conviction only if evidence clearly supports a criminal indictment — not to solve political problems, provide weeks of suspenseful cable TV news programming, or to pacify mobs.

Prosecutors and judges take solemn oaths not to bring charges they cannot in good faith support. It’s a cornerstone of our fundamental freedoms.

But when even President Obama finds it necessary to urge calm after a grand jury decision in Missouri — fat lot of good that did — I’m left wondering if maybe a nationally televised criminal trial wasn’t exactly what the situation in Ferguson required. Not that it would necessarily have changed anybody’s mind about the death of Michael Brown at the hands of Officer Darren Wilson. Nor led to a different outcome.

Probably Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon should have appointed a special prosecutor. However, given the facts of the case as somewhat clumsily presented by St. Louis County prosecutor Robert McCulloch, but more importantly based upon the evidentiary file his office released, even a negligent homicide conviction of Officer Wilson was never going to happen.

Missouri law gives cops wide latitude to use deadly force when threatened by an assailant. We’ve all seen juries refuse to convict cops in circumstances far more ambiguous than this tragic case presents.

However much McCulloch’s law enforcement background — several family members are cops — may have influenced his view of the evidence, it definitely hampered his presentation. To me, he appeared to assume that his audience would react to certain parts of the story exactly as he and his colleagues in law enforcement would.

Clearly, many have not. For example, have you seen a single hyperventilating lefty acknowledge that at minimum Michael Brown committed felony assault? Maybe McCullough needed to say so. I’m fairly confident that when African-American parents have “the talk” with their sons about dealing with white cops, they don’t advise punching an officer who stops them to ask about a strong arm theft they just did.

Nor, when the cop draws his weapon, taunting that “You’re too much of a f***ing pussy to shoot me.”

Now that the evidence is out there, however, it should be incumbent upon the same news media that turned this sorrowful tragedy into a televised melodrama to put things into a fuller and more realistic context.

Observing (and sometimes participating in) social media exchanges, one gets used to people making categorically false statements about the case, and then doubling-down when corrected — never acknowledging error, but finding new rationalizations for pre-existing beliefs.

“The cop did NOT stop him to ask [Brown] about a robbery,” an advocate of the murdering racist-cop theory haughtily informed me. “At no point did that happen. Just goes to show how people continue to make up their own version of this tragic event — no matter what facts have been actually been presented, never mind corroborated.”

Even prosecutor McCullough’s murky summary, however, established that Officer Wilson had heard about the convenience store robbery on his radio, noticed that Michael Brown fit the suspect’s description, observed the (stolen) cigars in his hand, and called for backup. Radio transmissions and transcripts documented these things.

Not to mention that Brown himself certainly knew he’d just done a robbery — and here came a cop.

And why should it matter? I suspect because it’s just as important for some people to see Michael Brown as an innocent set upon by a cop filled with racial malice as it is for others to depict him as a marauding black thug.

Purely tribal reasoning of this kind is common in political arguments, of course, which is pretty much what Ferguson has boiled down to: a partisan loyalty test.

Writing in Vox, Ezra Klein asks many of the right questions:

“Why did Michael Brown, an 18-year-old kid headed to college, refuse to move from the middle of the street to the sidewalk? Why would he curse out a police officer? Why would he attack a police officer? Why would he dare a police officer to shoot him? Why would he charge a police officer holding a gun?”

In that sense, he finds Darren Wilson’s testimony “unbelievable” — not in the sense that he’s lying, but that his story “raises more questions than it answers.”

Indeed, it does. My own view is that irrational behavior most often stems from irrational causes, and that tragedy often follows.

An early New York Timesprofile of Michael Brown told of his texting cell phone photos to his parents just weeks before he died to document his visions of Satan fighting angels in the sky over Ferguson, MO.

With everybody obsessing about race, nobody’s mentioned what a psychiatrist might suspect: that Brown had suffered a psychotic break.

And cops end up killing mentally ill people in this country all the time.

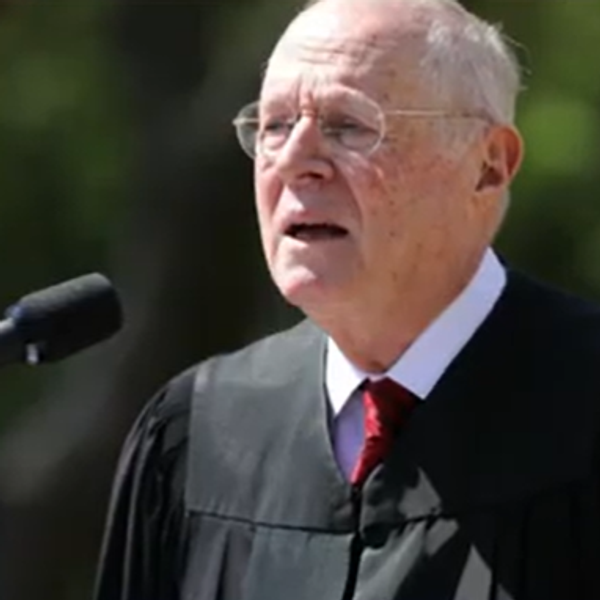

Photo: St. Louis County Prosecutor Robert McCulloch announces the grand jury’s decision not to indict Ferguson police officer Darren Wilson in the Aug. 9 shooting death of Michael Brown on Monday, Nov. 24, 2014, at the Buzz Westfall Justice Center in Clayton, Mo. (Cristina Fletes-Boutte/St. Louis Post-Dispatch/TNS)

Want more political news and analysis? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!