How Conservative 'Reform' Literally Cut Off A Texas Prisoner's Right Arm

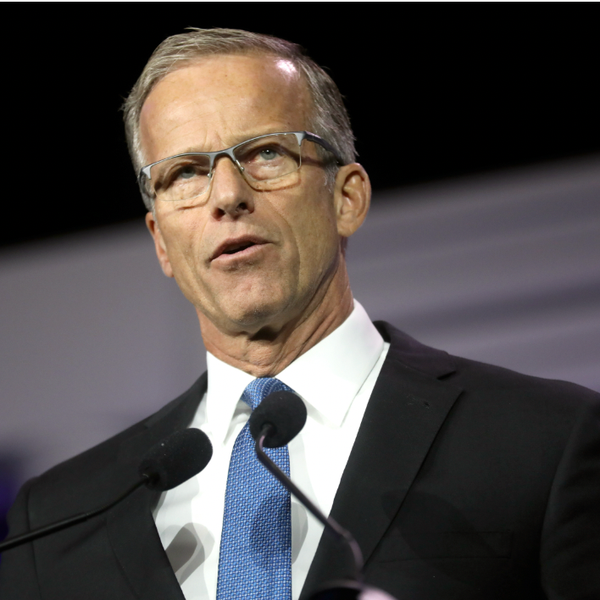

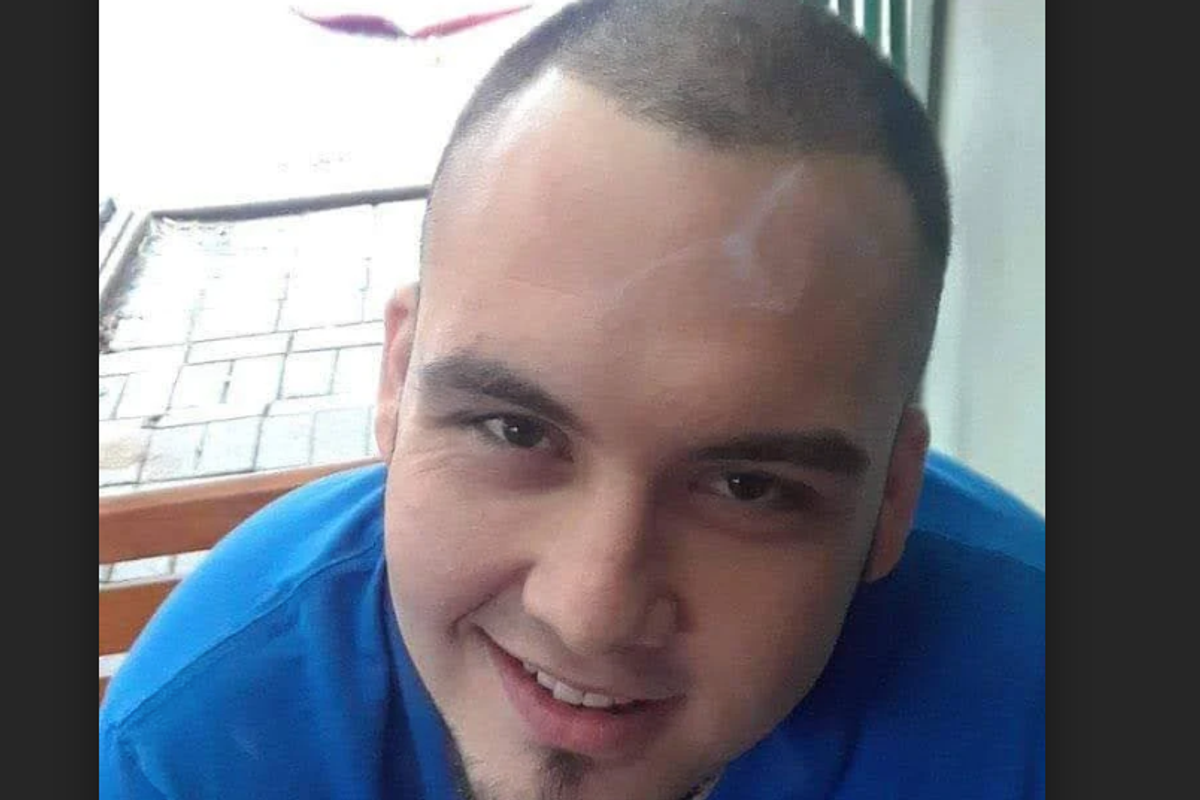

Greg Corley

Denton County, Texas is home to about 941,647 people and sports five separate criminal courts. That excludes civil actions and leaves one criminal court for every 188,329 people. Denton County Commissioners expect business to be brisk.

On February 9, 2022, one of those 188,329 patrons, Greg Corley, tested positive for COVID-19, an event that’s become almost routine for millions of people. But the stakes were higher for Corley; the Denton County Court expected him to appear that day on a case for drug and firearm possession that had been pending for about a year.

At that point, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had given up on the 10-day quarantine about six weeks earlier and halved it to five days. But even with the shorter isolation period, the infected Corley couldn’t and shouldn’t have appeared in court on February 9. So he emailed the court administrator with a copy of his COVID test results.

The court issued a rearrest warrant anyway for his absence. The court administrator offered Corley two dates to come in and see if 462nd County Court Judge Lee Ann Breading would vacate the warrant; one of the dates, February 14, fell squarely within the five day quarantine period. He could have appeared on February 15, but Denton County Court administrator offered Corley the date of February 22, the Tuesday after the long President’s Day weekend.

Corely never had a chance to appear on that date because the bond company arrested him on the outstanding warrant on February 15, 2002. Bounty hunters, and then Denton County Sheriffs, handcuffed Corley behind his back and thereby dislodged a stent the detainee had placed years before to correct an old motorcycle accident injury. The displaced stent blocked blood flow to his arm.

And the 1996 federal statute, the Prison Litigation Reform Act, blocked Corley from restoring it. To date, blood isn’t flowing in Corley’s right arm.

The Prison Litigation Reform Act, or PLRA, attempted to curb the number of federal lawsuits filed by inmates, many of which were described as frivolous. Retrospective analysis suggests that the evidence presented in support of passing the law was twisted in a way to make meritorious claims look frivolous, but the goal was to reduce the number of civil claims, which were overwhelmingly filed by self-represented prisoners trying to address conditions of their confinement.

The statute addressed a number of aspects of federal litigation from behind bars: filing fees, a three-strikes provision, and a requirement that inmates sustain physical injuries in order to have standing to sue jailers.

But the most consequential part of the PLRA is its exhaustion requirement; the law required anyone who wanted to sue over correctional conditions to run through all possible avenues of resolution before filing suit.

The exhaustion requirement wasn’t a bad idea — if one assumes good faith on the parts of everyone in the system, a dicey proposition in prisons and jails. That someone shouldn’t make a federal case, literally, about a problem until he searches for all solutions isn’t unreasonable by itself. But, as Corley’s case demonstrates, the exhaustion requirement has turned into an excuse and delay tactic rather than a focus on real fixes.

Corley started filing medical grievances on March 6, 2022, and the exchanges between him and jail staff soon became a master class in gaslighting; almost every answer to his increasingly panicked requests for help agreed that he needs clinical treatment while also denying it. In his first complaint, Corley wrote that he asked for medical care for the first two weeks of being in custody and was denied. The lack of care became so severe that he described being taken to the medical unit to see if a “pulse could be found for [his] right hand.”

Denton County’s Medical Grievance Board responded to Corley: “You have a medically indicated, physician directed (sic) care plan in place. You’re encouraged to continue to address your medical needs with the Correctional Health Team,” which is exactly what he was doing.

When Corley complained again a week later, he wrote: “I was called to medical to do a check for pulse on right arm. Nurse tried for 10 minutes to find pulse. No pulse found. She noted that hand is swollen, purple and cold, no blood flow to hand. She informed physician who refused medical care and sent me back to my cell. Note that this is the second time in one week that medical attention has been denied.”

Five days later, the Medical Grievance Board replied: “Previously addressed.”

On March 29, 2022, Corley complained that he asked a guard “to call medical because they did not call me for a medical appointment yesterday. He told me it was not his problem and to go sit down. I asked for a grievance form and an envelope and he denied me both.”

“The officers are not required to communicate with medical for you,” the Medical Grievance Board responded, which wasn’t what Corley had requested.

On another grievance filed by Corley two days later, he reported that a nurse “stated she could see and feel the red swollen hot area on my hand and wrist where obvious blood infection has started to form.” A week later, the same Medical Grievance Board decided, and expressed through custody staff: “This is a clinical concern that needs to be addressed with correctional health. In the interim, all encounters are reviewed by a physician.”

One of the reasons why Corley’s arm got caught in this administrative cycle is that the PLRA was unconstitutional from the start; it allows employees of a correctional facility to decide administrative remedy applications, complaints about their treatment of an inmate.

Almost 100 years ago, the Supreme Court made law in a case where judges in Prohibition-era Ohio where local mayors were allowed to decide cases and then be paid extra for every defendant found guilty. According to our highest court, when a decision maker has “a direct, personal, substantial, pecuniary interest” in a controversy, the right to due process is violated, even when the decision makers have only good intentions

Yet the Medical Grievance Board that adjudicated all of Corley’s complaints consists of two members, neither of whom are physicians. John Kissinger and Shannon Sprabary oversaw all of Corley’s complaints — and they’re two correctional health managers at Denton County Public Health who have financial interests in keeping the county’s costs down and a personal interest in looking blameless.

It’s not just possible, it’s probable, that Greg Corley’s arm has been sacrificed as a matter not of justice or clinical judgment, but of the business of criminal prosecution.