Will Medicaid Introduce A Standard Of Care (At Last) For The Incarcerated?

“Dog, please help me. Please. You know, Dog, what it's like. Please be the one to help me.'"

As he sat in jail at Oahu Community Correctional Center, itching to be free, Frank Hampp pleaded with the bail bondsman-cum-reality television star Duane Chapman, a.k.a. Dog the Bounty Hunter.

Hampp was facing a weapons charge. His mother worried about him. He had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder in 2014 and his treatment had been spotty. She called the jail staff and informed them that her son had been diagnosed with bipolar disorder and required medication. After his mother’s phone call, Hampp started receiving medication for his mental illness, although not the right one. Hampp requested that the psychiatrist re-evaluate him to modify his prescription which didn’t happen.

Instead, in what may be considered an unlucky turn, Dakota Chapman, Dog’s grandson, sprung Hampp on October 3, 2017. Hampp was released with no medication and no appointments for further follow-up.

Within three days, Hampp had cut off his electronic monitoring device and was on the run. He missed his January 9, 2018 court date.

The effects of his untreated illness brought him back to custody in a much more serious circumstance than was necessary.

In late January 2028, Hampp fled a routine traffic stop in Waianae, a town about 24 miles outside of Honolulu, because he had missed his court date. After police eyed him in an allegedly stolen car, Hampp took them on a chase, shooting at them and eventually crashing into a fence and fire hydrant.

Hampp took off again, this time into a friend’s apartment where it appeared that two women and a man were not allowed to leave while Hampp was inside. Waianae Specialized Services Division officers surrounded the building and, eventually, all three residents left the apartment.

He could have been charged with taking hostages and other crimes, but Waianae Police charged Hampp with three counts of first-degree attempted murder and one count of felon in possession of a firearm and set his bail at $1 million.

At OCCC, despite the chaos that brought him into custody and the fact that jail records from only months before indicated that he needed psychiatric medication, Hampp received no treatment. One day, when he was being escorted to a new housing assignment, Hampp threw himself over a balcony in an attempt to take his own life. He survived his suicide attempt but is now a paraplegic.

“What ifs” perplex Hampp, his family, and his legal team; he’s one of the lead plaintiffs in a class action suit against OCCC for failing to adequately manage its wards' mental health needs.

What if Hampp had left OCCC with a prescription and an appointment with a provider? What if he was taking the proper pills when Da Kine Bailbonds showed up to help him out? What if he was taking medication during that traffic stop that eventually spun out of control and ended with attempted murder charges? What if he had been medicated upon his rearrest? Would he be walking today?

Hampp’s case demonstrates the promise of the Justice-Involved 1115 Waiver Demonstration Project and the questions about these projects that remain unanswered.

Medicaid Especially Promising For Jails

Under the approved new demonstration projects, both of which will commence at some time in 2024 in California and Washington, the only two states approved for the waiver so far, Medicaid coverage will be available for eligible incarcerated individuals in jails, courthouses, prisons, juvenile and community residential centers.

Eligible inmates — those with behavioral health needs, including mental health disorders, substance use disorder, certain other health conditions, and incarcerated youth — will receive Medicaid coverage for a period of up to 90 days immediately before their release. They receive a targeted benefit package that will include case management services (securing appointments on the outside) medication-assisted treatment for substance abuse disorders while they are still awaiting release, a 30-day supply of medications upon release, and certain other supportive services.

Allowing Medicaid to cover detainees for 90 days before departure is an especially compelling prospect.

For years, the average jail stay was around 33 days, according to the Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics. This length of stay stays well within the 90-day limitation in the demonstration project rules allowing them to get coverage upon admission.

Recently, a study of three specific jails indicated that the average jail stay may be rising. In 2019, those charged with violent crimes who were admitted to the Louisville-Jefferson County, Kentucky Jail, the St. Louis County, Missouri Jail or the Durham County, North Carolina Jail spent, on average, more than 100 days in custody, as compared to fewer than 40 days for a nonviolent felony and fewer than nine days for a misdemeanor.

Waiting longer than 90 days for the resolution of one’s charges doesn't necessarily make a jail detainee ineligible for coverage. When someone is not yet sentenced and awaiting determination of the date they will leave — either to go home or to state prison — they still may be within 90 days of their release from the facility.

Theoretically, any unsentenced detainee in a jail is within 90 days of release because so much about their length of confinement remains unknown. A detainee in Frank Hampp’s position would be covered in one of these demonstration projects because he was, at any given time, within 90 days of release, even if he left the facility by posting bond.

The 1115 Waiver Demonstration Projects may enable entire jail populations to be covered by Medicaid, an unprecedented development in correctional healthcare.

Implementation Is Still A Future Prospect

No matter how these 1115 waivers are understood — either as allowing jails and prisons to become a part of the health system or moving the healthcare infrastructure into jails and prisons — they introduce one federal policy in all carceral places. If the Medicaid Inmate Exclusion Policy (MIEP) no longer applies, even if in these exceptional demonstration projects alone, it unifies the system in a way that makes it easier to achieve widespread improvement in outcomes.

It’s not clear how any of this will happen. In California, the Department of Health Care Services is still collecting information from counties; implementation of the program has been pushed back to October 2024 and it will be even later in Washington. States approved by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in 2024 are likely looking at 2025 for implementation.

Implementation methods and strategies will vary, just as policies differ now.

For example, 16 states pause Medicaid upon arrival in a jail or prison, another 16 suspend after a certain time and 18 states disenroll a beneficiary the moment they become incarcerated. The difference these varying policies make is significant; undoing a suspended enrollment involves less time and effort than re-enrolling a patient.

The use of electronic medical records (EMR) is another complication states and localities must face as they either implement an 1115 waiver project or await approval from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid. Some jurisdictions’ medical record systems are still paper-bound. Others have electronic medical records, but not the type of EMRs that are compatible with Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services payment systems. None will be able to seek reimbursement unless their computer systems are compatible and it remains to be seen how that will happen, how much it will cost, and how much it may delay full-scale implementation.

All but 11 states and an unknown number of local jurisdictions implemented copays for medical care in jails and prisons, not necessarily to offset costs, but to set up a disincentive system for inmates using the healthcare apparatus for reasons other than receiving care. That is, prison officials are trying to weed out legitimate claims of medical need from inmates who may be misusing the system, a rare but real occurrence.

Healthcare for incarcerated people is a patchwork ungoverned by one guiding policy. Thousands of stories on these particulars and others await the 1115 waiver demonstration projects. It’s the stories of these differences that will show why Medicaid eligibility for inmates is so promising.

Why 'Criminal Justice System' Is A Misnomer

The “criminal justice system” is a misnomer. It’s not one system. There’s a federal system, another 50 state systems, and systems that 38,779 general-purpose municipal governments use to detect, respond to, and prosecute crime. And there’s no single oversight body or policy for all of them. The best proxy that this country had for an overarching, national policy on carceral healthcare was the Constitution, requiring laws that have to apply in all spaces equally. That’s why, in the past, any hope for getting incarcerated people the care that they need came from the courts, tribunals that are almost impossible for inmates to access without counsel.

Whether or not the Supreme Court of the United States overturns Estele v. Gamble, the seminal decision that guaranteed healthcare for incarcerated persons, states and counties are moving away from an Eighth Amendment framework. Statutory changes would work the best. But they’re not likely.

In September, during a special legislative session, the West Virginia state legislature rammed through Senate Bill 1009, which banned the use of state funds for any healthcare for incarcerated people that isn’t deemed “medically necessary.”

The state's Corrections and Rehabilitation Commissioner Billy Marshall — whom Bolts magazine has called “a career law enforcement agent who has said incarcerated people are lying when they allege inhumane treatment by the state” — is the only party who decides what “medically necessary” means. The law makes clear that the commissioner’s decision can trump medical advice.

“A provider of health care prescribing, ordering, recommending, or approving a health care service or product does not, by itself, make that health care service or product medically necessary,” the law reads. West Virginia is one of the ten states that did not expand Medicaid. No other state has a similar bill proposed, but West Virginia is just an example of how difficult it will be to create a statutory framework that protects prisoners’ health.

At the very least, Medicaid in jails and prisons eradicates the lower standard of care that we have tolerated for people who are incarcerated. It’s unclear whether anyone can fix the justice system by using that system's own levers to do it. It’s possible that the only way to generate enough disorder and chaos inside of the system to change it is to crash it into the healthcare bureaucracy. And that’s exactly what a Justice-Involved 1115 Medicaid Waiver Demonstration Project does.

Chandra Bozelko served more than six years in a maximum-security facility in Connecticut. While inside she became the first incarcerated person with a regular byline in a publication outside of the facility. Her “Prison Diaries" column ran in The New Haven Independent. Her work has earned several professional awards from the Society of Professional Journalists, the Los Angeles Press Club, The National Federation of Press Women and more. Her columns now appear regularly in The National Memo.

Antonio "Tony" Smith. Photo credit: Travella Casey

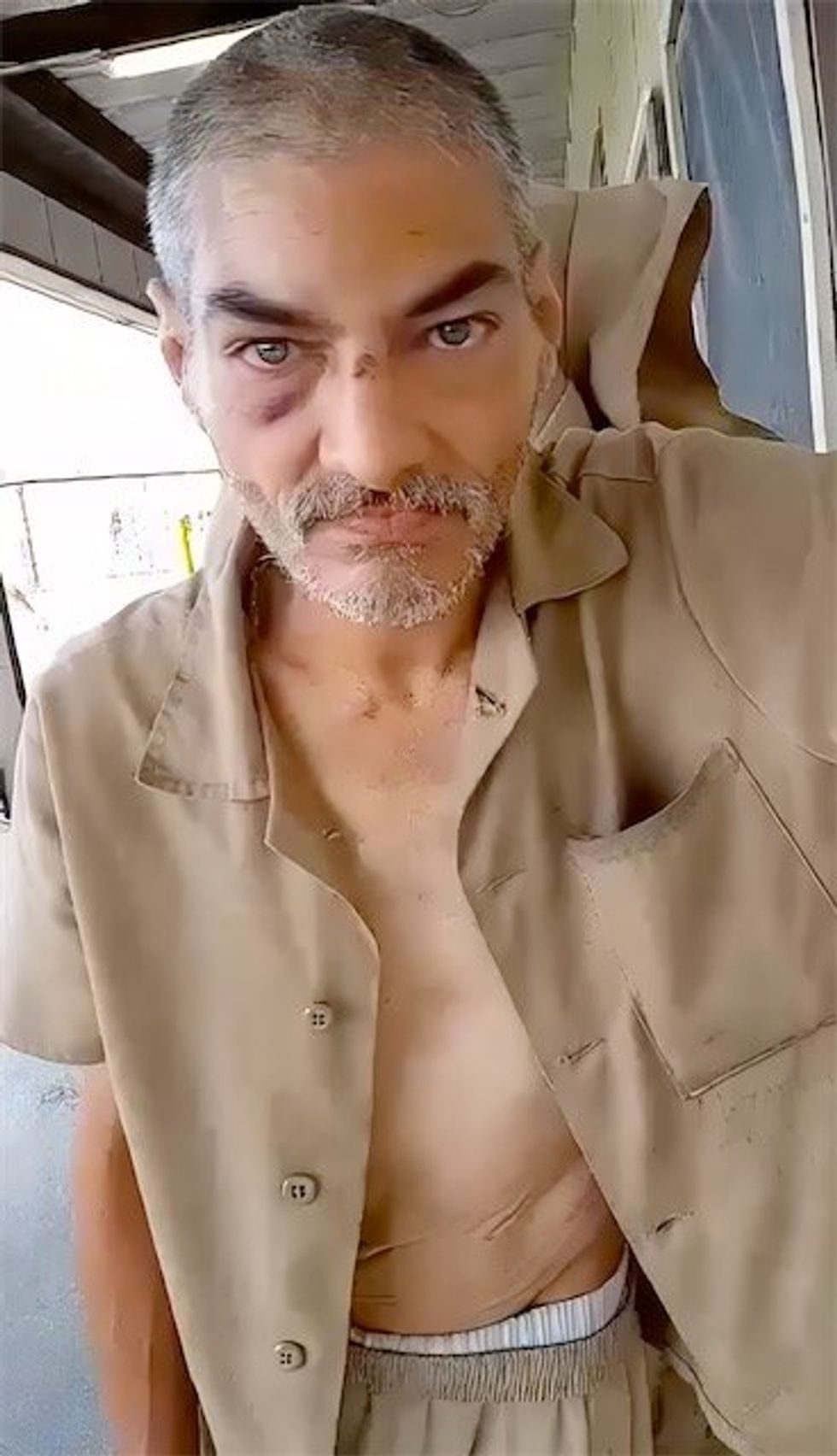

Antonio "Tony" Smith. Photo credit: Travella Casey Allen Jacob Hebert.Photo credit: Bernard Jemison.

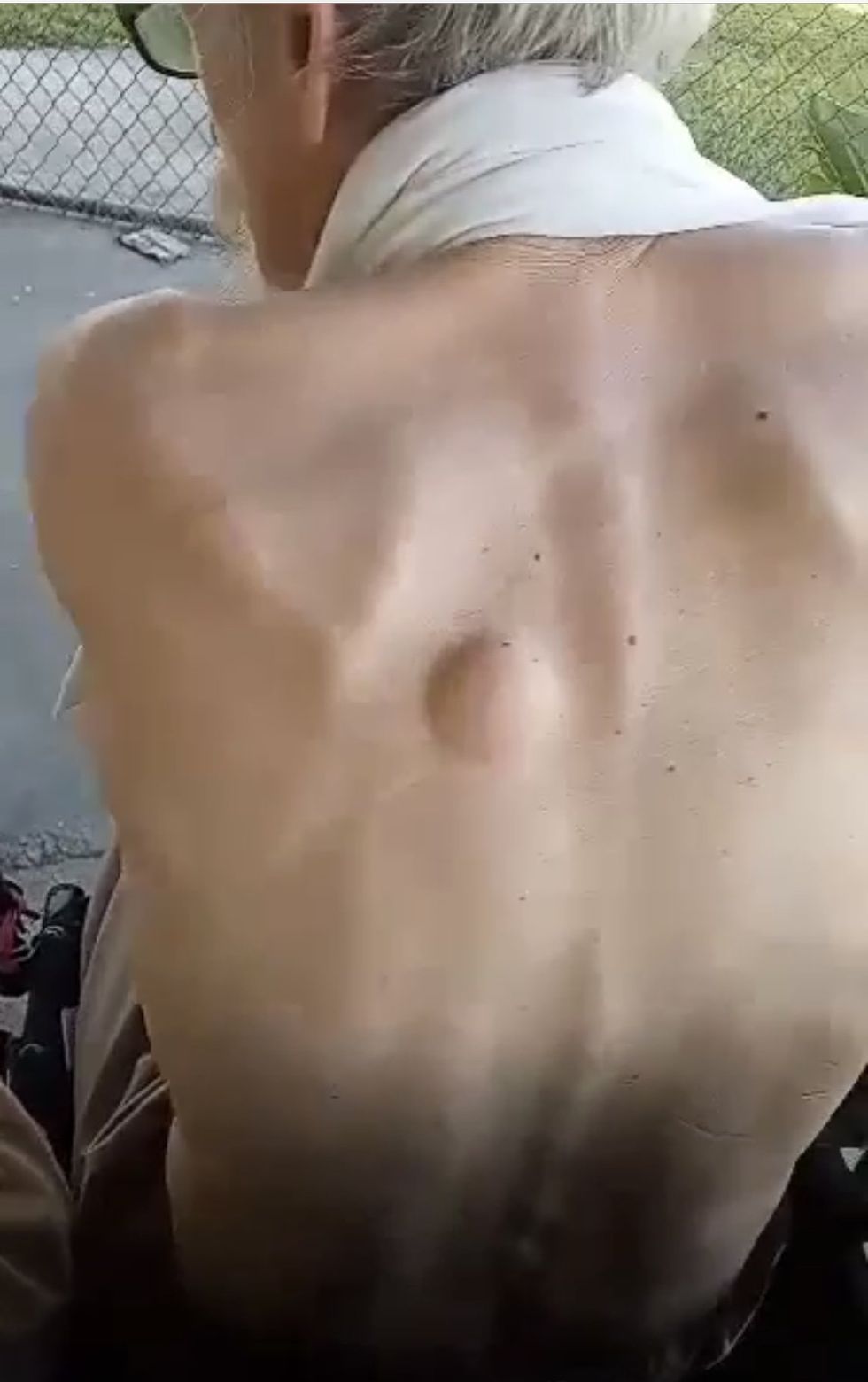

Allen Jacob Hebert.Photo credit: Bernard Jemison. Nolan Williams.Photo Credit: Bernard Jemison.

Nolan Williams.Photo Credit: Bernard Jemison. Nolan Williams' back.Photo Credit: Bernard Jemison.

Nolan Williams' back.Photo Credit: Bernard Jemison.

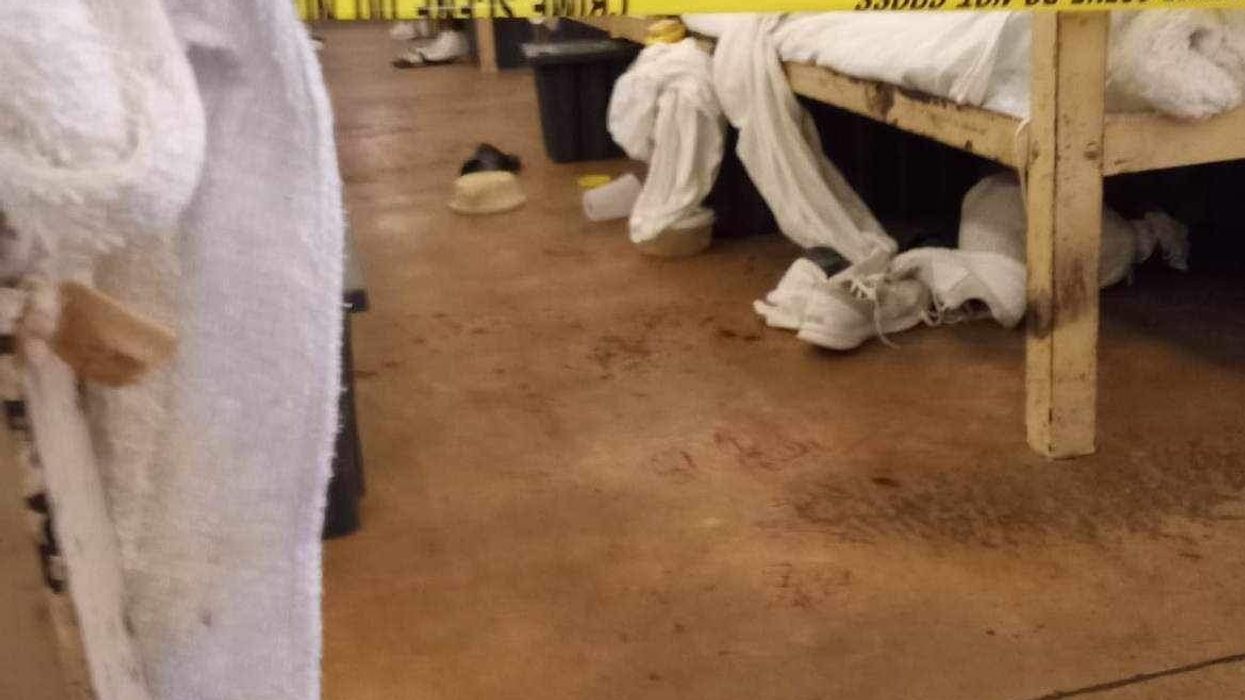

Eddie Ward

Eddie Ward