By David Hunn, St. Louis Post-Dispatch

FERGUSON, Mo. — The first call came on a Thursday, 12 days after Michael Brown was shot. Patti Knowles and her granddaughter were watching “Mickey Mouse Clubhouse.”

The caller warned that the collective of computer hackers and activists known as Anonymous had posted data online — her address and phone number and her husband James’ date of birth and Social Security number.

Anonymous had been targeting Ferguson and police officials for days. But this seemed to be an error. Patti and James weren’t city leaders, they were the parents of one — Ferguson Mayor James Knowles III.

Within hours, identity thieves had opened a credit application — the first of many — using the leaked data.

The second call came on a Friday, nearly two months later. This time, it was their bank.

Someone, posing as James, the mayor’s father, had called in and changed passwords, addresses and emails. Then the individual sent $16,000 in bank checks to an address in Chicago.

The name on the address?

Jon Belmar. Same as the chief of the St. Louis County police.

Knowles figured Anonymous was either aiming to frame them both — or was just being mischievous. Belmar, who has been targeted previously, refused to discuss the issue with the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. His wife had spent hours every day for weeks dealing with fraud and identity theft.

Anonymous denied responsibility for sending the checks.

“Pfffttt. No. Sounds like corruption if you ask me,” an organizer for Anonymous’ Operation Ferguson, who wouldn’t give his or her name, said in an email to the newspaper.

But Anonymous openly claims credit for the first set of actions: Scouring the Internet for personal and private financial information on hundreds if not thousands of police officers, mayors, judges and officials, in governments big and small, worldwide.

Two years ago, a hacker affiliated with Anonymous claimed he published the personal information of former CIA chief and four-star U.S. Army General David Petraeus and his wife, Holly.

In March, Anonymous targeted Albuquerque, N.M., after the fatal police shooting of a homeless man. Hackers went after the mayor, police chief and multiple officers.

“I think we’re just seeing the tremors of what can happen,” said Peter Ambs, Albuquerque’s chief information officer. “Nobody is immune. It’s not a matter of if, but when. … How much money are we going to have to spend on hardening our systems, monitoring them to the point of locking them down so they have no value to anybody?”

Here, Anonymous operatives have outed at least 18 police officers, officials and residents over the past three months.

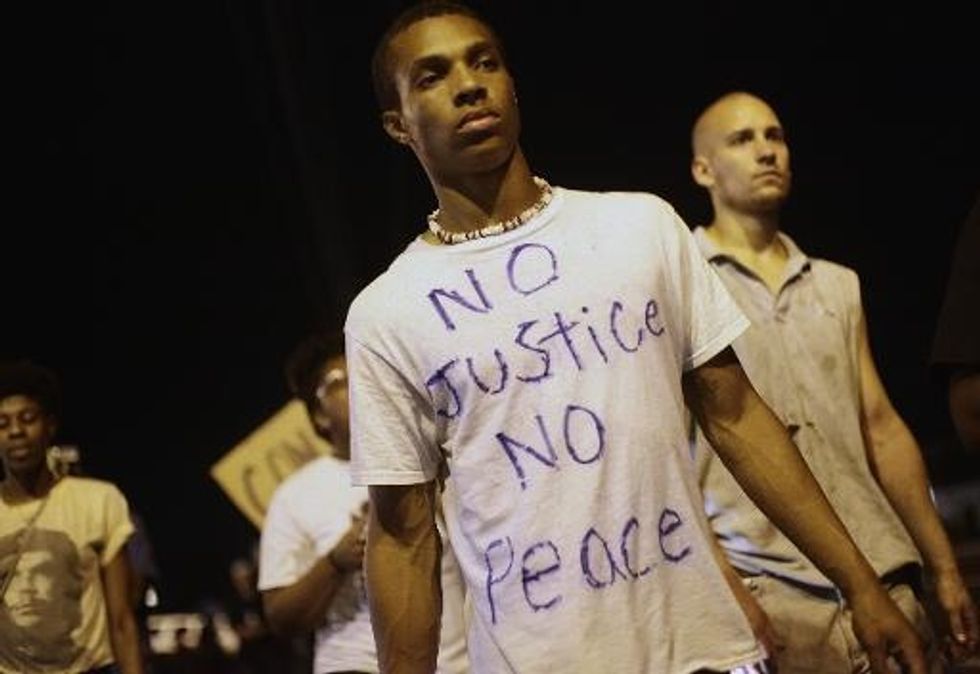

It started in the first days after Brown’s death.

Just after 5 p.m. on Aug. 9, rapper and local activist Kareem Jackson, known as Tef Poe, sent out a call for help: “Basically martial law is taking place in Ferguson all perimeters blocked coming and going,” he wrote on Twitter. “National and international friends Help!!!”

Jackson didn’t return a call seeking comment. Jackson’s attorney, James Wyrsch, denied that the intent of the tweet was to request the involvement of Anonymous.

Still, Anonymous responded to Jackson within hours, and, by the next day, had created the Twitter account OpFerguson, plus a warning on YouTube:

“We are watching you very closely. If you abuse, harass or harm in any way the protesters in Ferguson we will take every Web-based asset of your departments and governments offline,” Anonymous’ idiosyncratic electronic voice hummed. “That is not a threat. It is a promise.”

Anonymous said it would begin publicly releasing personal information “on every single member of the Ferguson Police Department,” among others.

Then it did.

Early on the morning of Aug. 12, hackers posted county police chief Belmar’s home address and phone number online. They tweeted pictures of him, his house, his wife, his children. “You said our threats were just hollow,” wrote TheAnonMessage. “See, that makes us mad. You shouldn’t challenge us.”

Anonymous isn’t a group with members or a sign-up list. Informal leaders set up operations, chat rooms and often identify targets. Others then jump in.

On Aug. 20, they posted personal data on Ferguson Police Chief Thomas Jackson. On Aug. 22, Col. Ronald Replogle, superintendent of the state highway patrol. On Sept. 18, Gov. Jay Nixon. And on Sept. 20, Steve Stenger, St. Louis County councilman and county executive candidate.

It’s unclear who used the data following the releases. OpFerguson said it didn’t care.

But the consequences are clear.

Jackson said identity thieves used his information to buy a horse in Turkey. Ferguson police Sgt. Harry Dilworth said someone tried to purchase a $37,000 truck in his name. All six Ferguson City Council members have signed up for an identity-theft alert service.

Even those unconnected to Brown have been affected.

Dilworth said one of the officers he supervises, mistakenly outed by Anonymous as Brown’s shooter, ended up moving his family out of state.

The social media pages of St. Ann dispatcher Bryan Willman, also errantly identified as Brown’s killer, were so flooded with death threats, he shut them down. St. Ann police stationed a car outside his house; he didn’t leave for nearly two weeks, Police Chief Aaron Jimenez said.

Jimenez called for more federal scrutiny. “I certainly hope the FBI is going to take this seriously, and make an example out of Anonymous,” he said. “Enough is enough.”

Joe Bindbeutel, chief of the Consumer Protection Division with the Missouri attorney general, said it’s tough to fit such actions into the conventional criminal code and tough to locate the operatives. “The real pros at this are really hard to find,” he said.

The FBI, which has worked with websites to take down Anonymous postings, declined to comment for this story.

Knowles got two calls on Aug. 21. The highway patrol called first. The officer thought Knowles’ personal information was posted online.

Then Knowles’ mother called. She had gotten at least four calls warning of the barrage to come.

Knowles told his father to sign up for LifeLock, a protection service. Before the day was done, the company, which monitors the use of clients’ names and Social Security numbers, had contacted the family with a credit application in his father’s name.

The next day, there were three more. Two, the following day. Then two more. And so on.

The hackers accessed the Knowleses’ bank accounts, changed passwords, emails and home addresses. They changed the Knowleses’ home phone number _ a number they’ve had for 35 years. They set up credit cards, cellphones, home loans.

“Why would somebody do that?” his father asked.

But the $16,000 brought Patti Knowles to tears. The money was pulled from their business accounts — they own a heating and cooling company — and the temporary loss (the bank refunded the cash) led to bounced checks, included one to the IRS for business taxes.

The bank declined to say whether the checks were cashed.

The data leaks led to other problems, too. Someone, for instance, broke into a house they owned, tore out some piping and left water pouring into the basement. Knowles’ father found the house in 6 inches of standing water. The basement — two bedrooms, a full bath and family room — had to be gutted.

But the most frustrating moment for Knowles’ father came at the start of October. His wife noticed they hadn’t gotten any recent LifeLock notices.

When he tried to call, the company wouldn’t let him into this own accounts. Someone, it seemed, had broken into LifeLock, too.

“I pay you money to protect my stuff,” Knowles’ father said. “And you get hacked?”

A spokeswoman for LifeLock declined to comment.

Knowles was irritated, calling the Anonymous actions criminal. Still, the mayor seemed to have had largely evaded the same fate.

Until a few days ago.

“Excuse me Mr. Mayor,” OpFerguson tweeted Tuesday, “the communications director wanted me to tell you, “Anonymous just leaked your credit card data.”

Anonymous emailed late Saturday that the tweet was a joke.

For now.

AFP Photo/Joshua Lott

Interested in more political and national news? Sign up for our daily email newsletter!