More Anger, Action At Ferguson Commission Meeting

By David Hunn, St. Louis Post-Dispatch (TNS)

ST. LOUIS — Anger again overtook the Ferguson Commission, in its second meeting Monday night, with residents and protesters packing aisles of a school gymnasium and shouting down speakers.

“We’re tired of the bull crap!” yelled Anthony Levine, 46, from Florissant.

At its peak, attendance swelled to about 250, with protesters filling aisles, sides and the back of the gym at Mullanphy School in the city’s Shaw neighborhood – across the street from the memorial to VonDerritt Myers Jr., who was shot and killed this summer by a St. Louis police officer.

The meeting got off to a smooth start. The governor-appointed commissioners restructured the agenda this time, starting with a half-hour meet-and-greet, and then a half-hour of public testimony. Speakers were punctual and respectful.

But after about an hour, the commission asked St. Louis Police Chief Sam Dotson to the microphone. Boos rang out from the crowd almost instantly.

Dotson tried to give a prepared speech. But the room began to fill with protesters and residents frustrated with official responses to the recent string of police shootings. And they wouldn’t let Dotson talk.

“Man, your two minutes are up,” one yelled. “Get off the mic.”

At the same time, residents in attendance got frustrated with the outbursts.

“Well, technically this meeting is over,” said Acme Price, 82, a University City resident and a former Mullanphy School principal.

Price had been worried about outbursts. “If they’re going to create a success, the commission needs to be thrown out of these buildings,” he said earlier Monday. “They need to get a travel bus, like they’re going on vacation, and ring doorbells.”

One commissioner, local attorney Gabriel Gore, said he watched acquaintances leave, as the shouting continued.

Still, he said, it was only a handful of speakers talking over everyone. The rest of the meeting progressed about as it should, he said. And the next one, he predicted, would be even better.

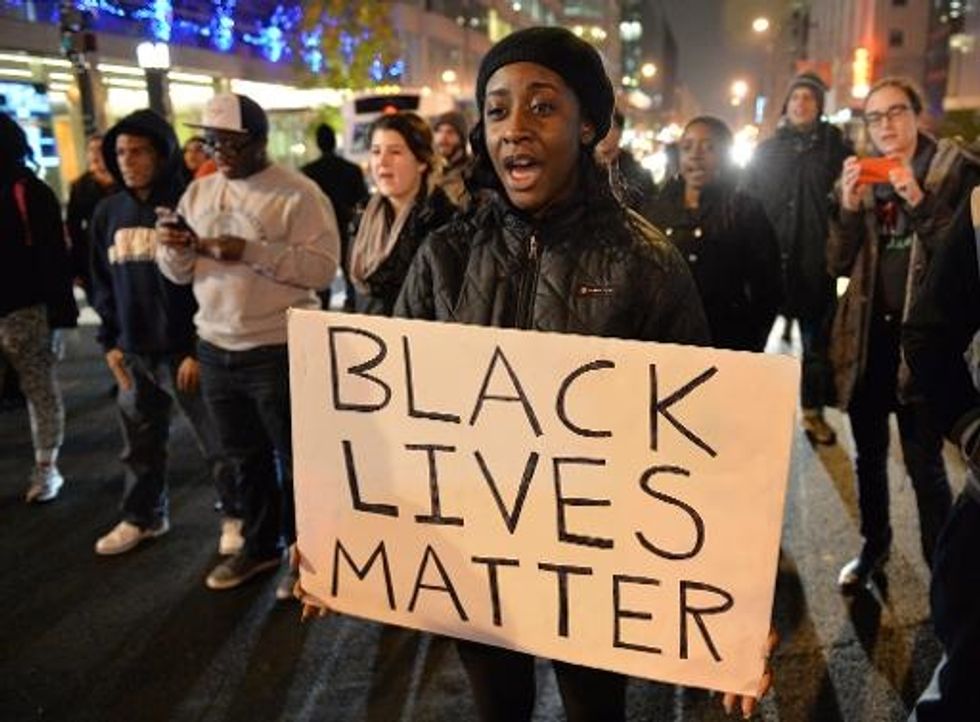

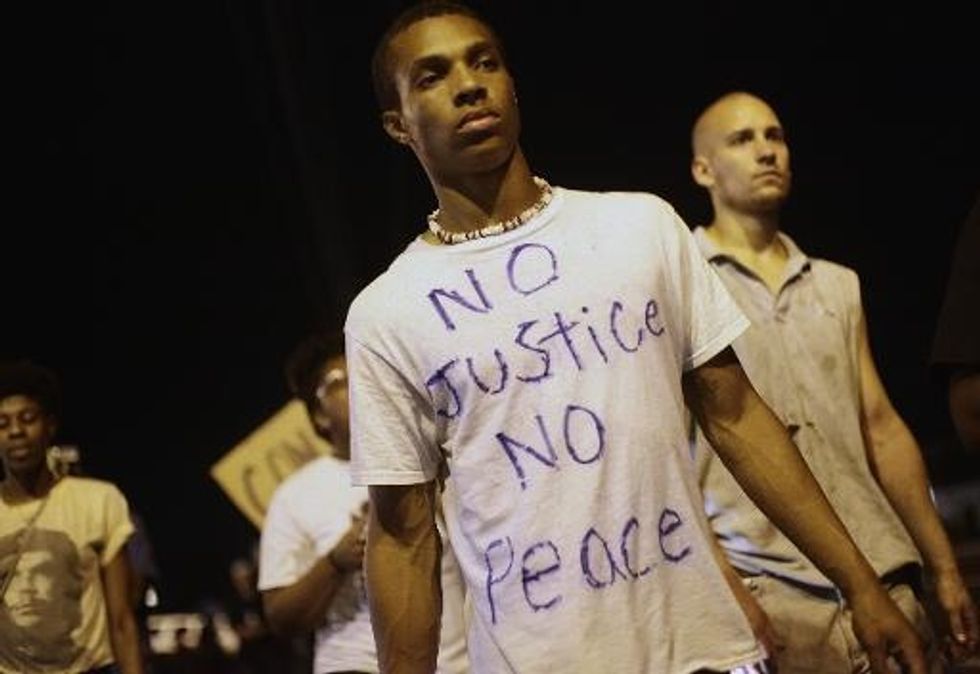

Nixon announced the commission in October and its members in November. He asked them to address the “social and economic conditions” highlighted by months of protests surrounding the killing of 18-year-old Michael Brown, who was black, by Ferguson police Officer Darren Wilson, who is white.

Nixon said the group would have three goals: to study the underlying causes of the unrest, to tap into expertise needed to address those concerns, and to make specific recommendations for “making the St. Louis region a stronger, fairer place for everyone to live.”

The commission opened its first meeting Dec. 1 inside a half-full gymnasium at the new community center in Ferguson. Fourteen of the 16 commissioners attended. The meeting was scheduled for five hours. But after three, some in the audience got frustrated that they hadn’t yet been given time to speak. Several jumped up to voice their opinions.

Monday’s meeting was even larger, perhaps double the attendance of the week prior. More gathered in the aisles and sides. More yelled.

Still, the commission also got more of the hard work done. After at least 50 residents and protesters left, mid-meeting, the commissioners broke the remaining 150 or so into three groups, where they hammered out common ground concerning police, use-of-force, racial-profiling and community relations, among other topics. That was the good, hard work, commissioners said.

“Citizens were talking to each other,” said co-chairman Rich McClure, after the meeting. “They were giving great feedback.

“I understand what leads,” he continued. “But that was an incredible time. Don’t lose that.”

As the meeting closed, co-chairman Starsky Wilson asked for 30 seconds of silence.

By then, the protesters had largely left. Residents were listening.

And the gymnasium at Mullanphy went silent, with hardly a cough, barely a murmur, for the first time that night.

The next meeting will be at 5 p.m. next Monday.

It will tackle predatory municipal court practices. The commission is seeking residents who have been victims themselves to speak at the meeting.

AFP Photo/Mladen Antonov