Comey Prosecution Appears Doomed After Federal Judge Eviscerates Halligan's Conduct

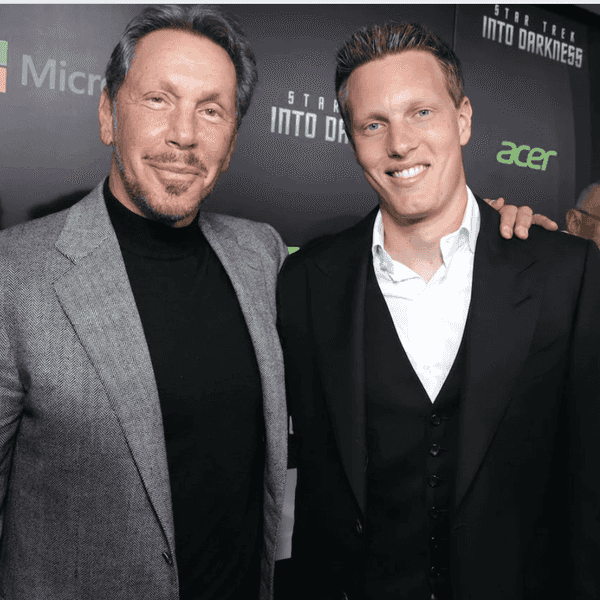

LIndsey Halligan

Lindsey Halligan has had some very bad days since Donald Trump attempted to shoehorn her into the position of United States Attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia with marching orders to bring him the scalps of Jim Comey and Tish James. But yesterday was her worst day, and it points to far worse ones still to come.

The cause of her miserable Monday was a meticulous and blistering memorandum opinion from Magistrate Judge William Fitzpatrick in United States v. Comey. The 24-page decision eviscerated her and the entire prosecution.

Fitzpatrick’s opinion lays out a sequence of investigative, procedural, and constitutional failures so fundamental that they threaten the viability of the indictment itself. The judge details a cascade of basic yet grave errors by a U.S. Attorney and a Department of Justice that have veered miles off the rails.

The catalog is long, and it culminates in a finding that Halligan misinstructed the grand jury on points of law so elementary that any first-year law student in a prosecutorial-tactics class would know to avoid them. That same student, it bears noting, would have had more relevant experience than Halligan, who was plunked into the highest job in the office and then proceeded to appear solo before the grand jury despite having had exactly zero experience as a federal prosecutor.

Combine that preposterous assignment with the political imperative to deliver indictments for the Maximum Leader in cases that were themselves threadbare, and you had the perfect setup for overreach and blunder in the grand jury room. Unsurprisingly, that is precisely the trap Halligan walked into. It is hard to see her professional reputation emerging intact.

The opinion traces the misconduct back to Trump 1.0 and the 2019–20 “Arctic Haze” investigation. FBI agents obtained warrants to search devices and email accounts belonging to Columbia Law Professor Daniel Richman, James Comey’s longtime attorney and confidant.

Richman’s role as Comey’s lawyer should have set off immediate alarm bells, because of the extreme risk to a prosecution of viewing, much less using, documents covered by the attorney-client privilege. That is why as a general rule, no member of an investigative or prosecutorial team may review attorney-client privileged material; that responsibility lies with a separate “taint” team of uninvolved attorneys and agents.

But Fitzpatrick found that the agents charged with the initial review went far beyond the warrant’s limits. Worse, they held onto that material long after the investigation had closed and failed to conduct any meaningful privilege review despite knowing Richman represented multiple clients, including Comey. Most remarkably, Comey—the privilege holder himself—was never included in the screening process. And notwithstanding a court order to seal and refrain from reviewing nonresponsive material, the government effectively treated the entire trove as fair game for rummaging—a practice the Fourth Amendment was designed to prevent.

That was the landscape when Halligan was rushed into service, after the previous nominee, Erik Siebert, told DOJ leadership that the case could not be brought under DOJ guidelines. That assessment, implicating a core duty for any federal prosecutor, amounted to a fireable offense in Pam Bondi’s Justice Department.

From there, as Fitzpatrick documents, things descended into chaos. Facing an imminent statute-of-limitations deadline on a newly imagined charge, the government went back to the Richman materials without seeking any judicial authorization. Fitzpatrick understatedly called the maneuver “highly unusual.” A new warrant would have required the government to define a relevant timeframe, establish probable cause for the new charges, and—critically—implement protections for privileged material. None of that occurred.

The next misstep was yet more jaw-dropping. The FBI agent assigned to search the extracted Richman materials was expressly told to look for communications between Richman and Comey—communications that were, by definition, presumptively privileged. He found them, printed them, and handed them to another agent, who recognized their privileged nature. Yet that recognition did not trigger a taint protocol, a recusal, or even a pause. Instead, Agent-3, who had been exposed to what Fitzpatrick describes as at least a “limited overview” of privileged content, went on to testify as the sole witness before the grand jury. Every word of his testimony may have rested on tainted material.

Then came Halligan’s performance before the grand jury. Fitzpatrick identified two separate statements she made that were “fundamental misstatements of the law that could compromise the integrity of the grand jury process.”

The statements themselves are redacted, but Fitzpatrick describes their contours. In the first she suggested to the grand jury that Comey might not have a Fifth Amendment right not to testify at trial—or that, at a minimum, the trial jury would be instructed not to draw any inference from his silence. It is hard to imagine a more basic or consequential legal error.

And she was not done. Halligan also told the grand jury it could rely on information not presented to it when determining probable cause and assured the jurors that the government had more—and perhaps better—evidence elsewhere.

It is difficult to imagine a prosecutor in the pre-Bondi DOJ who could have committed errors this basic and prejudicial and remained employed—or, at the very least, not been shunted off to an obscure corner where further harm was impossible. But in this DOJ, Halligan’s amateurism, combined with her anything-it-takes approach to serving Trump, is her most prominent qualification.

Things only deteriorated from there. The grand jury initially rejected Count One of the proposed charges—an unusual event. The rejection so unsettled Halligan that she botched the presentation of the returned indictment to the court. This has prompted sharp questioning from both Fitzpatrick and Judge Currie, who is overseeing a separate motion arguing that Halligan’s appointment was unlawful and ineffective.

Halligan has submitted a declaration swearing she had no contact with the grand jury after deliberations began. Fitzpatrick, reviewing the timeline, plainly does not buy it. His conclusion is stark: either Halligan is “mistaken” about when she learned the grand jurors had rejected Count One, or “the Court is in uncharted legal territory in that the indictment returned in open court was not the same charging document presented to and deliberated upon by the grand jury.” Those are two astonishingly bad options for Halligan.

By the end of the opinion, Fitzpatrick lists no fewer than eleven grounds supporting the defense’s request for disclosure of grand jury materials. They include possible Fourth Amendment violations; willful or reckless misconduct by investigators; mishandling of privileged documents; tainted testimony; constitutional misstatements; and profound irregularities in the indictment’s return. The cumulative impact is a judicial finding that Comey has shown a rare “particularized and factually based” basis to challenge the indictment’s validity—the exact showing Rule 6(e) requires. Findings like this are extremely uncommon.

For Halligan, the opinion marks a moment of extraordinary vulnerability. Even before it, she faced serious legal and ethical concerns: doubts about the legality of her appointment; sanctions in prior litigation; a reported unwillingness to follow DOJ protocols for politically sensitive investigations; and, above all, her willingness to sign on to reprisal prosecutions against Trump’s perceived enemies in defiance of everything DOJ once stood for.

None of this should shock us, or, for that matter, Halligan. She accepted the role of pretend prosecutor, tasked with bringing plainly illegitimate cases on Trump’s say-so. Now the case has metastasized, and it is far too late to turn back. Trump may well shield her from criminal liability with a pardon, but he cannot protect her professional reputation, which is irretrievably wrecked, or spare her from a bar discipline process, which is already underway.

Most importantly, the case Halligan volunteered for—which I have called “the single most shameful act in the Department of Justice’s history”—now appears to be in a death spiral. The only remaining question is which court and which legal tool will finish it off. And when that happens, the fallout will land squarely on Lindsey Halligan.

- Irredeemable Justice: Letitia James' Indictment Tolls The Depth Of Corruption ›

- The 'Weaponization Of Justice' Began During Trump's First Term ›

- Celebrated Former US Attorney Will Defend Comey Against Trump's Toy Prosecutor ›

- The Bitter Ironies Behind Trump's Tyrannical Indictment Of James Comey ›

- Halligan's Retribution Prosecutions Of Comey and James Are Falling Apart Fast ›

- She's Prosecuting Comey For Trump, But Lindsey Halligan Isn't Having Any Fun ›

- Judge appears skeptical of government's actions as Comey, James ... ›

- Lindsey Halligan says 'there are no missing minutes' in grand jury ... ›

- James Comey wants case dropped, Trump's prosecutor disqualified ›

- The Situation: Malevolence, Incompetence, and the Strange Case of ... ›

- Halligan and Bondi push back on judge's suggestion that Comey ... ›

- Judge who reviewed James Comey's indictment was confused by ... ›

- Judge says possible errors by Lindsey Halligan could imperil ... ›