In Trump's Georgia Ballot Seizure, Election Denial Outweighs Evidence And Law

Before the affidavit supporting the Fulton County ballot seizure was unsealed, the mystery was what evidence could possibly justify a search warrant for election materials from 2020. Now that we have seen it, the mystery is how this one—so plainly deficient in probable cause—was approved at all.

The affidavit is vacuous at the center. It identifies no suspect. It alleges no criminal intent. It does not explain how the materials sought would establish the elements of a federal offense. Instead, it assembles a series of recycled allegations about supposed election “deficiencies” and concludes that if those deficiencies were intentional, the seized materials would constitute evidence of violations of federal law.

That conjectural leap is not a substitute for probable cause.

The affidavit invokes two statutes: 52 U.S.C. § 20701 (record retention) and § 20511 (knowing and willful election fraud). Yet it never alleges knowing or willful conduct by anyone. It does not identify who committed a crime, when it occurred, or how the elements were satisfied. Nor does it explain how the requested materials would demonstrate criminality rather than everyday administrative error of the sort that is common in a large election office.

More striking still, the affidavit recites findings that cut directly against any inference of criminal intent. It quotes a bipartisan Performance Review Board that found “no evidence of fraud, intentional misconduct, or large systematic issues” affecting the 2020 result. The affidavit does not rebut or distinguish that conclusion. It simply moves past it.

The same pattern repeats for other essential elements. The affidavit recycles old allegations, long parroted by election deniers, about duplicate scans, unsigned tabulator tapes, ballot images, and “pristine” absentee ballots that state officials and others previously have examined and dismissed. The affidavit recounts those contradictory determinations yet nevertheless goes on to treat the underlying discredited, or at best highly contested, claims as grounds for a sweeping criminal seizure.

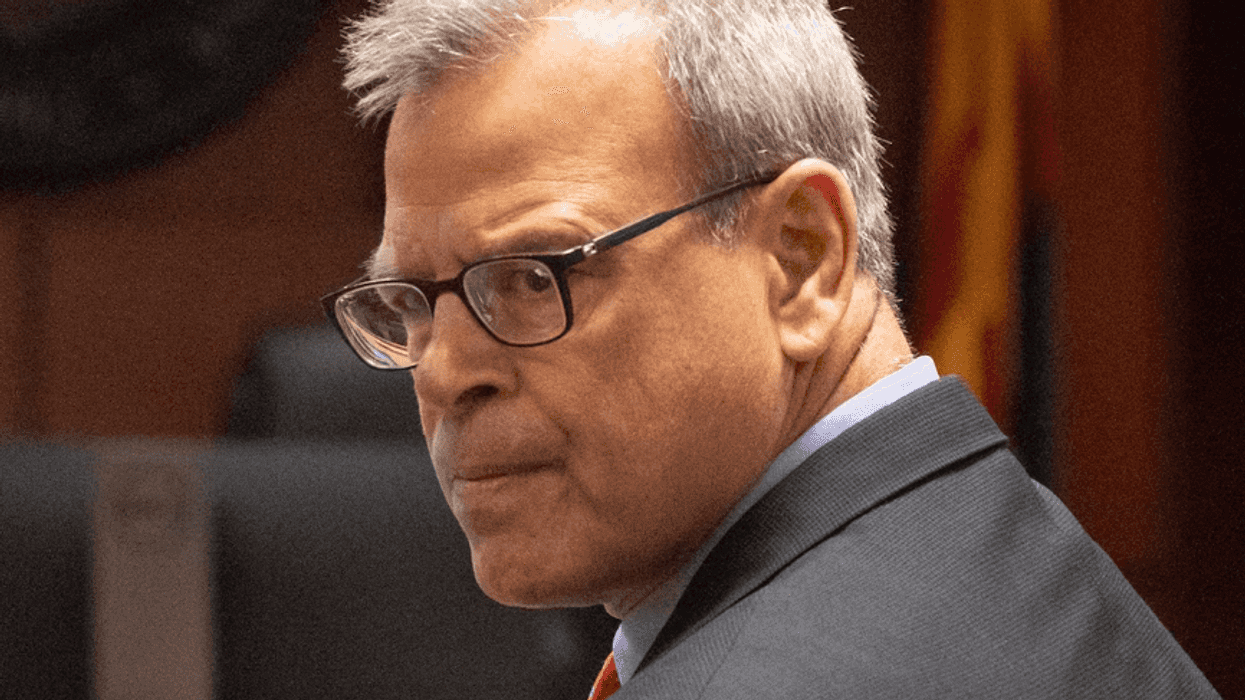

Nor does it explain to the magistrate why the actual sources of information are credible and reliable. An affidavit can rely on second-hand information, but it needs to demonstrate that the information is trustworthy at the source, for example by showing the source has previously given solid intel. That failure is especially glaring here given the reports that the driving force behind the current investigation was a referral from a notorious and longstanding election denier, Kurt Olsen, now Trump’s Director of Election Security and Integrity.

The affidavit also fails to grapple with staleness. The election occurred in November 2020. Much of the investigative activity described took place in 2021 and 2022. The warrant didn’t issue until years later. The probable cause standard encompasses a requirement that evidence not be stale. The affidavit doesn’t speak to that point at all, which is telling, since so many of the allegations are old and recycled. The record retention charge conceivably could be ongoing, but even as to that, an affidavit must show that the evidence of violation is fresh. Likewise, the document doesn’t engage with statute-of-limitations constraints that would bear on any conceivable prosecution.

The immense scope of the warrant only magnifies these defects. The magistrate authorized seizure of all physical ballots, ballot images, tabulator tapes, and voter rolls from the 2020 election. This is not a narrowly tailored search tied to a defined criminal theory. It is a comprehensive removal of an election archive based on broad speculation rather than concrete allegations of wrongdoing.

Most strikingly, after reciting a series of recycled allegations—many of which have already been examined and rejected—the affidavit in its penultimate paragraph offers this gem:

“If these deficiencies were the result of intentional action, the election records identified in Attachment B are evidence of violations of 52 U.S.C. §§ 20511 and 20701.”

Er, yes—and if the elements of a crime were satisfied, there would be a crime. Probable cause requires a fair probability that those elements, including the requisite mental state, have in fact been established. Saying “if these deficiencies were the result of intentional action” is not evidence of intent. It is an acknowledgment that intent has not been shown.

It is hard to miss the neon sign blinking: the affidavit does not establish probable cause, because, among other reasons, it provides no evidence on an essential element of the crimes in question.

As a former federal prosecutor, I know what would have happened had I submitted a draft like this for review. It would not have been fun. The first question a supervisor would have asked would have been, What, precisely, is the criminal offense? The second: Where is the evidence of intent? The third: How does this search establish each element? Those questions are not rhetorical flourishes. They are foundational. An affidavit that cannot answer them does not get filed, both because it would violate Fourth Amendment rights and because it would harm the office’s credibility.

In our polarized climate, it is tempting to assume the magistrate was politically captured. But there’s no basis for that conclusion. The magistrate here is a respected former public defender with deep criminal-law experience and a sophisticated understanding of probable cause doctrine. That makes the approval perplexing—but it does not ground a more cynical explanation.

I think the most plausible account is that the approval was an error by a conscientious professional. That happens. Unfortunately, this one carried real consequences.

The FBI has removed roughly 700 boxes of ballots and related materials from Fulton County. Courts are often reluctant to unwind a seizure immediately; suppression or return typically occurs, if at all, in later proceedings. And now that it has all the goods, it is not even clear that DOJ is contemplating criminal charges.

This is where the stakes of the case, and the consequences of the flawed warrant, come clear.

Recall that in January 2021, Trump browbeat Georgia’s Secretary of State Brad Raffensberger to “find 11,780 votes.” He did not ask for proof of fraud. He asked for a number—just enough to reverse the result. Raffensberger turned him down, doing right by the country.

But now, armed with this treasure trove of ballots and voter data, the administration could attempt to do on its own what Trump couldn’t do by haranguing. The raw election materials in the FBI’s possession could allow for a frontal attack on results that Trump couldn’t undermine with the rear-guard action in 2020. Ongoing “review” of ballots can justify calls for federal intervention. Access to voter rolls can fuel aggressive eligibility challenges and purge efforts.

Or consider the other Georgia heist Trump was plotting in 2020: getting a DOJ flunky to send a letter falsely claiming that the Department had detected fraud in the count. As Trump chillingly put it, “just say that the election was corrupt and leave the rest to me and the Republican Congressmen.” The broader lesson here is if Trump can foment chaos and create turbulence on the ground, he is halfway home to reversing particular election results.

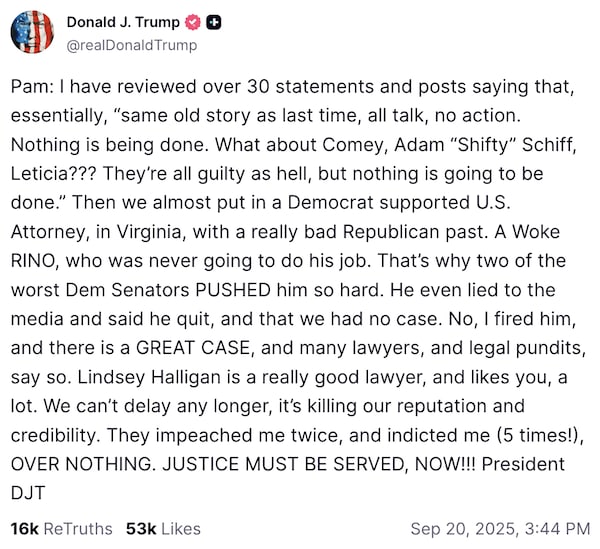

We know that the administration is zealously seeking the same sort of information the warrant provided in over a dozen states around the country, all part of Trump’s call to Republicans to “take over the voting in at least many — 15 places. … The Republicans ought to nationalize the voting.”

It’s a goal they are pursuing in all corners. That’s the explanation for Pam Bondi’s bizarre suggestion that the Department would pull back on Operation Metro Surge in Minnesota if the state would turn over access to the state’s voter registration lists. And you can bet some similar agenda is in play for the upcoming meeting on February 25 that the administration has called for state election officials from all 50 states.

Fulton County is not taking it lying down. The County Commission and Board of Registration and Elections have filed an emergency motion under Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 41(g), seeking return of the seized materials.

Rule 41(g) permits a person aggrieved by an unlawful search to seek return of property. When no criminal charges are pending—as here—the district court exercises equitable jurisdiction. The movant must show a possessory interest and that continued government retention is unreasonable. If the warrant lacked probable cause or exceeded statutory authority, the court may order the property returned.

The County argues that the affidavit failed to establish probable cause; that the cited statutes do not support any viable prosecution; and that DOJ bypassed ongoing civil and state proceedings to obtain through a sealed criminal warrant what it had been seeking through supervised litigation. It also points to concrete harms: Georgia law requires original ballots to remain sealed in state custody, and federal removal interferes with statutory duties and pending cases.

Meaningful relief under Rule 41(g) is rare. But given the conspicuous deficiencies in the affidavit, Fulton County has more than a symbolic argument. It has a fighting chance. Ultimately, however, that determination rests with the discretion of the district court after full adversarial briefing.

The bad news here is that now the government has seized original ballots and voter data, it has the wherewithal to make a disruption that cannot be entirely reversed. The good news is that the episode is essentially a one-off. It provides no precedent or momentum for the administration’s other efforts to seize voter data.

This essay began with a simple question: what happened to probable cause?

The answer should not be that it bent to political turbulence. If courts insist on what the Fourth Amendment requires—actual evidence of actual crimes—this will remain a cautionary, albeit damaging, episode, not a template for federal seizure of election materials elsewhere.

Harry Litman is a former United States Attorney and the executive producer and host of the Talking Feds podcast. He has taught law at UCLA, Berkeley, and Georgetown and served as a deputy assistant attorney general in the Clinton Administration. Please consider subscribing to Talking Feds on Substack.

Reprinted with permission from Talking Feds.