The American president, in addition to serving as commander in chief, is expected to be this nation’s consoler in chief, as well as the nation’s teacher and even preacher. Who alive on Jan. 28, 1986, does not remember the words of then-President Ronald Reagan from the Oval Office following the explosion of the Challenger that killed all seven astronauts on board, seen live on television by millions? Reagan reminded the country that “the future doesn’t belong to the fainthearted; it belongs to the brave” and closed with the words of a 19-year-old American pilot who perished in World War II and had “slipped the surly bonds of Earth” and “touched the face of God.”

We know the president is the head of government, but the president is also the head of state, expected to speak to and for all of us when the occasion demands. That is precisely what then-President Barack Obama did so well in Charleston, South Carolina, on June 26, 2015, at the service for Rev. Clementa Pinckney, one of nine victims executed by a terrorist at Emmanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church. Obama dared to lead the congregation in singing: “Amazing Grace/ How sweet the sound, That saved a wretch like me/ I once was lost/ But now I’m found.” He comforted the nation.

It is not only the remembered eloquence of Abraham Lincoln’s second inaugural address, which he gave as the Civil War, the nation’s bloodiest war, was coming to an end (along with Lincoln’s own life). “With malice toward none, with charity for all … let us strive on … to bind up the nation’s wounds, to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan,” he said. It’s also the largeness of spirit then-President George W. Bush showed at the Islamic Center of Washington following the deadly Sept. 11, 2001, attacks on the U.S. He reminded us: “The face of terror is not the true face of Islam. That’s not what Islam is all about. Islam is peace. These terrorists don’t represent peace. They represent evil and war.”

Contrast these presidential examples of seeking to unite the country at times of genuine crisis with President Donald Trump’s inability to rise to the challenge. Sadly, we remember the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, specifically organized by a group of white supremacists to celebrate the white nationalist movement and protest the planned removal of the statue of Confederate Gen. Robert E Lee. The “warm-up” had featured a torchlight parade with marchers chanting, “Jews will not replace us,” and “blood and soil,” which echoed Nazi Germany. The president insisted, “I think there’s blame on both sides … very fine people on both sides,” and that he had not been aware of former Ku Klux Klan David Duke’s prominent presence.

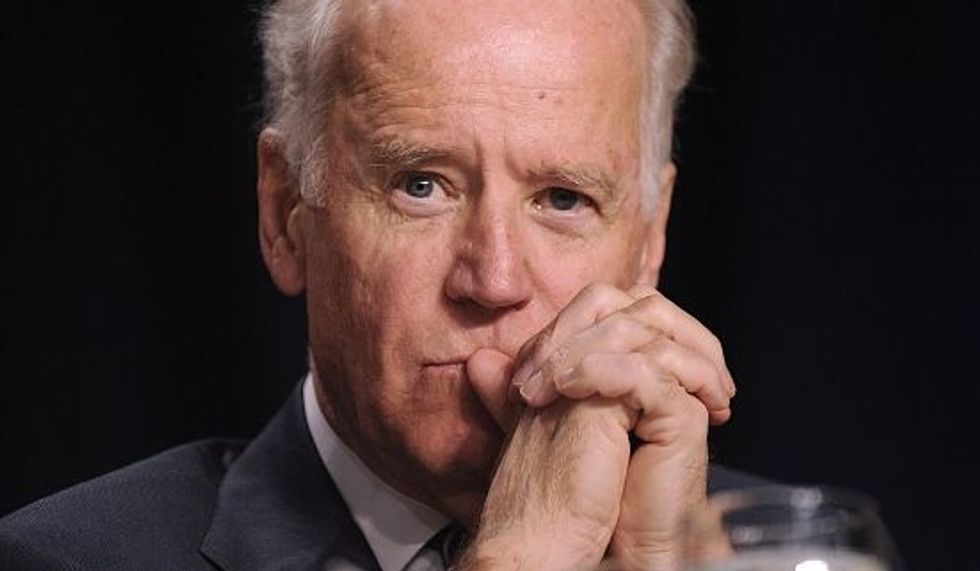

Here is former Vice President Joe Biden’s opening. Alone among American political leaders, Biden has been asked time and again by grieving families to give the eulogies at memorial services of Americans both famous and not. The family of Democratic presidential nominee George McGovern asked Biden to speak at the South Dakotan’s funeral, as did the family of Republican presidential nominee John McCain. So, too, did the families of two South Carolina giants, Republican Strom Thurmond and Democrat Fritz Hollings. Biden comforted Ted Kennedy’s mourners just as he did Michigan’s John Dingell’s and Alaska Republican Ted Stevens’.

There is now an obvious, gaping vacancy in the important role of consoler in chief, and in Joe Biden we have someone to fill it.

To find out more about Mark Shields and read his past columns, visit the Creators Syndicate webpage at www.creators.com.