After several days of unmitigated disaster — bad press, angry donors, baffled supporters, unwelcome scrutiny — the leaders of Susan G. Komen for the Cure, the world’s leading advocate for breast cancer research, moved to restore their credibility and calm the roiling waters that threatened to drown the organization in unfavorable reviews. It quickly became clear to Nancy Brinker, founder and CEO, that she had besmirched her brand with a politically driven decision to end a longstanding partnership with Planned Parenthood.

But the carefully worded public statement Komen released last week doesn’t quite end the story. Advocates for women’s health should watch carefully over the next several months to see whether Brinker and her board care more about helping less-affluent women get breast cancer screenings than they do about placating the anti-choice crowd.

For years now, Komen has been pressured by rigid anti-abortionists to stop making grants to Planned Parenthood, caricatured by its critics as solely an abortion provider. Last year, for example, the publishing arm of the Southern Baptist Convention, citing grants to Planned Parenthood, halted a brief campaign in which it sold pink bibles and donated some of the proceeds to Komen.

That pressure will only increase if the hardline anti-abortionists believe they had a near-victory snatched away suddenly. Komen may be looking for a quieter and less-obvious route to the same place: ending a relationship with a women’s health partner that has unfairly become a lightning rod.

Let’s look at the facts: Last year, abortions accounted for about 3 percent of the services provided by Planned Parenthood. Most of its funds go to a broad array of other women’s reproductive health services.

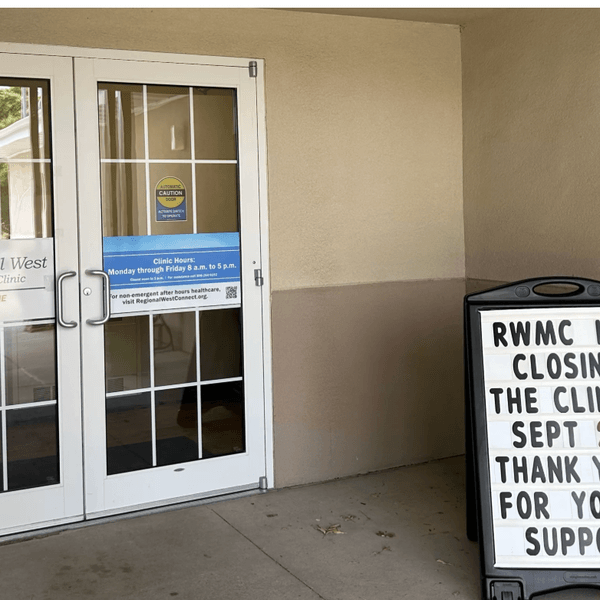

While its clinics across the country vary, most provide contraception. Many provide gynecological exams, treat sexually transmitted diseases and provide pre-natal care. (Yes, that’s right: Planned Parenthood provides medical care to pregnant women.) And some give vouchers for mammograms. That’s about as pro-life as it gets.

But leaders of the anti-abortion movement use a narrow and mean definition for that term, excluding children once they are out of the womb, women too poor to pay for mammograms and even pregnant women without medical insurance. Their health and welfare don’t get much notice from the pious right.

That includes ambitious politicians like Karen Handel, the Georgia politician who may have played a prominent role in Komen’s troubling initial decision. In 2010, Handel, Georgia’s former secretary of state, lost a bid to become governor despite an endorsement from Sarah Palin. Komen hired her last April as senior vice president for public policy.

While Komen has long prided itself on support from liberals, moderates and conservatives alike, Handel — who, like Palin, is bluntly anti-choice — was a curious hire. During the campaign for governor, she wrote, “Since I am pro-life, I do not support the mission of Planned Parenthood.” Indeed, she went so far as to pledge to eliminate state grants to Planned Parenthood for breast and cervical cancer screening and for prenatal care.

In an MSNBC interview last week, Brinker went out of her way to say that politics played no part in the earlier decision to end grants to Planned Parenthood. A statement released last week reiterated that: “We have been distressed at the presumption that the changes made to our funding criteria were done for political reasons. … They were not.”

That contradicts earlier statements made by board members and senior staff. Besides, it doesn’t pass the smell test.

In any event, Komen reversed the most obviously political policy — one that prohibited grants to any organization under investigation by “local, state or federal” authorities. That ended the outcry linked to a trumped up “investigation” of Planned Parenthood by U.S. Rep. Cliff Stearns, R-Fla., who is stridently anti-choice.

But Brinker has also suggested that stricter guidelines for grants played a role in the decision to deny funding to a longtime partner. While the reversal made clear that Komen will “preserve (Planned Parenthood’s) eligibility to apply for future grants,” the statement falls short of a wholehearted embrace.

Handel and her allies may win the battle for Komen after all.

(Cynthia Tucker, winner of the 2007 Pulitzer Prize for commentary, is a visiting professor at the University of Georgia. She can be reached at cynthia@cynthiatucker.com.)