Feb. 3 (Bloomberg) — So many times when the big credit- rating companies have embarrassed themselves, the world has sighed and chalked it up to a business model that by design invites corruption and incompetence. Perhaps never before have the public’s expectations for the industry been lower.

The fundamental flaw is that the major rating companies, led by Moody’s Investors Service and Standard & Poor’s, typically are paid by the issuers of the securities they rate, or by other deeply interested parties, such as Wall Street underwriters. Too often the raters seem to be the last to know that a company they dubbed investment grade was going broke, or that a mortgage bond once deemed AAA was about to default. The public sees these things and naturally draws a link between what the raters say and how they are compensated.

Although the government can’t make the credit raters more capable, it can make them more transparent. Here’s a good place to begin: Start requiring disclosures of how much the raters’ clients pay them for their services.

Consider some of the boilerplate in Moody’s reports on MF Global Holdings Ltd., whose credit ratings were the subject of a congressional hearing yesterday. Moody’s Oct. 27 report — in which it downgraded MF Global to junk, only four days before the futures broker filed for bankruptcy — said most issuers of debt securities pay “fees ranging from $1,500 to approximately $2,500,000” for “appraisal and rating services.”

It’s anyone’s guess whether the fees MF Global paid to Moody’s fell within or outside this range. The companies know how much money changed hands. They’re just not telling us.

The disclosures in Standard & Poor’s reports are just as useless. The company’s Oct. 26 report on MF Global said “S&P may receive compensation for its ratings and certain credit- related analyses, normally from issuers or underwriters of securities or from obligors.” Coincidence or not, S&P maintained an investment-grade mark on MF Global until the day it failed.

There’s no such secrecy about the fees other types of opinion vendors charge their clients. For more than a decade, U.S. public companies have been required to disclose the annual fees they pay their outside auditors. Similarly, when companies hire stock promoters or other firms to publish research reports profiling their shares, federal securities laws require disclosures in the reports showing who paid for them, as well as the amount and form of compensation.

The auditor-fee disclosures have been useful. Fannie Mae’s proxy statement for 2003, for instance, showed the housing financier paid KPMG $2.7 million to audit its books that year. The fee was so tiny, for a company with $1 trillion of assets, that it served as a red flag for investors, signaling that KPMG’s audit quality couldn’t have been all that robust. The next year Fannie Mae had a huge accounting scandal.

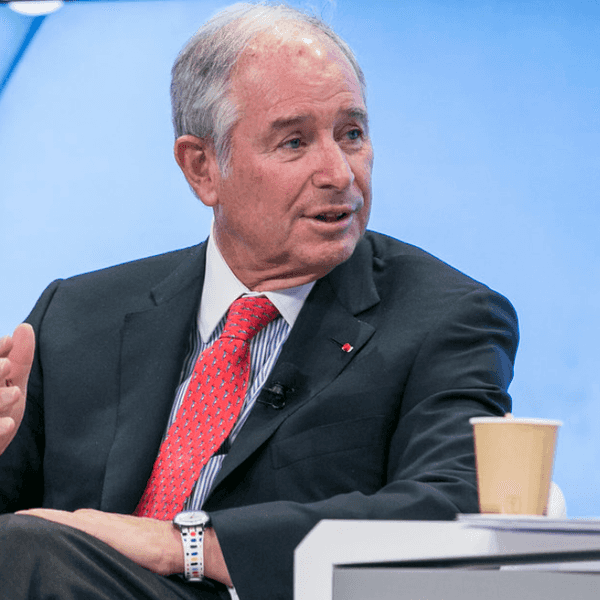

At the other extreme, in its first annual report as a public company, Blackstone Group LP said it paid its auditor, Deloitte & Touche, total fees of $159.1 million for 2007, mostly for non-audit work. The fees were so huge — Blackstone’s total assets were $13.2 billion at the time — it would be reasonable for investors to wonder what influence they might have had on Deloitte’s judgment.

The parallels for credit-rating companies are obvious. Like auditors and stock promoters, they’re paid to express opinions to investors. Whatever their fees are, the public should be told. The credit raters would have us believe there’s nothing wrong with collecting cash from the same customers whose securities they grade, and that this doesn’t cloud their independence or objectivity. If that’s true, they should have no problem with us knowing the actual dollar amounts.

Unfortunately this isn’t the path the government has chosen. The Dodd-Frank Act, passed in 2010, included 19 pages of new provisions governing how credit-rating companies operate. Numerous federal banking and securities laws were amended to remove statutory references to credit ratings, for instance, so that regulators would reduce their reliance on them. Dodd-Frank didn’t mandate disclosure of the raters’ fees, however.

A rule proposed last year by the Securities and Exchange Commission would require companies such as Moody’s and S&P to disclose in a form accompanying each credit rating whether the grade was paid for by the issuer, underwriter or sponsor of the security being rated — or if it was purchased by someone else, such as an investor. The rating company would also have to disclose if the purchaser had paid it for any other services, such as consulting or advisory work. Most important, though, no dollar amounts would have to be divulged.

This is a mistake. A big reason that the public doesn’t trust credit ratings is because of the money that changes hands. What matters most, obviously, is how much. It makes little difference whether the amounts are disclosed by the rating company or by the issuer of the securities as part of its own disclosures, as long as it’s made public somewhere.

The most dubious penny-stock promoters have to disclose what they get paid for their opinions. Credit raters can at least be held to the same standards.

(Jonathan Weil is a Bloomberg View columnist. The opinions expressed are his own.)

Copyright 2012 Bloomberg