Never Eligible To Vote, Young Immigrant Plays Key Role In Clinton Campaign

By Kate Linthicum, Los Angeles Times (TNS)

NEW YORK – Lorella Praeli has one of the most important jobs on Hillary Rodham Clinton’s presidential campaign – even though she’s never voted in an election.

As Latino outreach director, Praeli spends her days at Clinton’s headquarters in Brooklyn poring over polling data, winning endorsements from Latino leaders and fine-tuning the campaign’s messages to reach the nation’s fastest-growing bloc of voters.

A Peruvian immigrant who lived in the U.S. without legal status until three years ago, when she obtained a green card through marriage, Praeli hopes to obtain citizenship in time to vote in the election that she is helping shape.

That the campaign hired her speaks to the growing influence of the immigrant youth movement she helped lead as well as the distinct demographics of Latino voters.

The median age of Latinos in the U.S. is 27 – just like Praeli – and most Latino voters are either foreign born or the children of immigrants. To win over Latinos for Clinton in key states such as Florida, Colorado and Nevada, Praeli will have to connect with people much like herself.

But doing that is a monumental task. Twice as many Latinos will be eligible to vote next year as in 2000, but Latinos tend to turn out at lower rates than other groups, in part because many young Latinos aren’t engaged in politics.

“We have to give people a reason to vote,” Praeli says.

For Praeli, who came to the U.S. as a child to seek medical treatment, and whose mother still lives without legal status, the race is personal. She took the job in June shortly after Clinton pledged to do more than President Barack Obama to shield immigrants from deportation.

Praeli, who previously worked at United We Dream, one of the nation’s largest immigrant youth groups, played a crucial role in helping to convince Obama to expand his deportation protection program to include the parents of citizens and legal permanent residents. On the day he announced the expansion at a celebratory rally at a Las Vegas high school auditorium, Praeli stood in the front row, crying and clutching her mother, Chela.

A maid in New Milford, Conn., Chela would have qualified for the program. With it, she likely could have traveled to Peru for the first time in nearly 20 years to see her ill father. But that’s all on hold after the administration’s effort to limit deportations was blocked in court by Republican opponents who argue it exceeds Obama’s power.

“To all of a sudden have that pulled out from under you overnight, it makes you angry,” Praeli said in a recent interview, her fists clenched. The experience, she said, convinced her to leave advocacy to help elect a Democrat, a sentiment that has grown stronger in recent months, as Republican front-runner Donald Trump has called for dramatic measures to reduce illegal immigration.

“It’s not enough to sit on the sidelines,” she said.

Not all her former colleagues agree with that approach. Some activists complain Democrats have sought to co-opt the immigrant rights movement, and many have come to distrust promises from politicians. Obama, angling for Latino votes in 2008, pledged to pass immigration reform in his first year, but lost his chance by waiting to make a serious push until his second term. By then, Republicans controlled Congress and blocked efforts to rewrite immigration laws.

At a going away party for Praeli in Washington this summer, some colleagues ribbed her for joining forces with a politician.

“Good luck,” said the group’s managing director, Cristina Jimenez. “We’ll see you on the battlefield.”

Praeli has been a fighter since her childhood in Ica, Peru. She was 2 years old when a drunken driver hit another car and then slammed into her on the street, pinning her small body against a wall. Shortly after, doctors amputated her right leg just above the knee.

As she was learning to walk with a prosthetic leg, she often fell. Her father, who was involved in local politics, forbade anyone from helping her up, insisting she learn how to do it on her own. On hard days, he would sing to her in Spanish: “If you get up, you’ll fall. If you fall, you’ll get up again.”

That message – that there will be bumps in the road, but you will survive them – helped when the family moved without legal authorization to small-town Connecticut when Praeli was 10. An aunt lived there, and Praeli would have access to better medical treatment.

Her mother, trained as a psychologist in Peru, found work cleaning houses and looking after other people’s children. Her father returned to Peru a few years later, unable to get the hang of American life. (He and Praeli video chat frequently; last year, she called him from aboard Air Force One.)

In New Milford, where Praeli and her younger sister were the only Latinos at their elementary school, bullies took notice of Praeli’s prosthetic leg and glossy black hair and taunted her with slurs like “peg leg” and “border hopper.”

She stood up to them – printing out copies of their online jeers and delivering them to school police – and took revenge by excelling in the classroom. She attended Quinnipiac University on a full scholarship. But even as she embarked on academic studies of how municipal policies affect immigrants in the country illegally, she kept her own status a secret.

That changed in 2010, as hopes dimmed for a bill that would have created a path to citizenship for some young immigrants who came to the U.S. as children, known as Dreamers. Praeli contacted a leader of the Dreamer movement and a few weeks later was on her way to a meeting in Kentucky with hundreds of other young people in the country illegally.

That 16-hour van ride was life-changing, she said. Everybody seemed happy, and no one was scared. “It’s because they were building a movement,” she said.

The activists, borrowing from the gay rights struggle, talked about the importance of “coming out” – publicly disclosing their lack of legal status. “We wanted to create a moral dilemma in the country so when people say ‘undocumented,’ they know who they’re talking about,” Praeli said.

A few weeks after the Kentucky meeting, she had her own coming out moment at a news conference in New Haven, Conn. “For years I learned to be quiet and to live in the shadows and hide,” she told reporters. “I can no longer just sit and wait for something to happen.”

Praeli co-founded a nonprofit group, Connecticut Students for a Dream, and helped win passage of legislation that grants in-state tuition to university students in the country illegally. After she graduated, she married her U.S.-citizen boyfriend, Tim Eakins, and moved to Washington to push for an immigration overhaul.

Now Praeli is trying to bring to the Clinton campaign the savvy messaging and grass-roots organizing that made the Dreamers among the most successful civil rights activists of recent times.

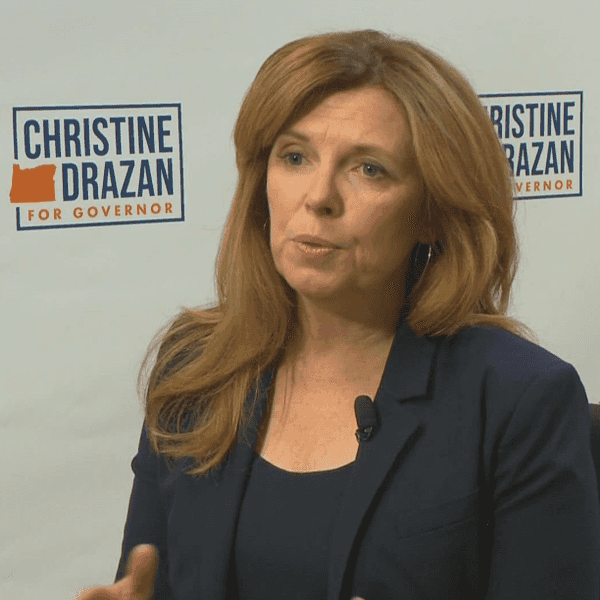

Photo: Lorella Praeli and her mom Chela Praeli via Twitter