The first time I met Marcia Grace, she adopted me as her project.

She was 5 at the time.

Marcia Grace was the niece of my future husband — I didn’t know that yet — and the youngest granddaughter of his mother, an intimidating woman of Southern grace and iron will. I was meeting her for the first time, too, and I was ridiculously nervous for a 45-year-old longtime single mother.

Even at 5, Marcia Grace was self-possessed enough to intuit my anxiety. She appointed herself my constant companion for the duration of the visit, until we left for a formal event.

Standing in her grandmother’s guest bathroom, I zipped up the first ballgown I’d owned in 20 years and tugged at the neckline with limited success. Three times I tried to steady my hand to draw a clean line on my eyelids. Three times I failed. Marcia Grace observed all of this from her perch on the closed lid of the toilet. Every time I sighed, she handed me another tissue from the box on her lap. “You’ll get it,” she said. “Just keep trying.”

It was so like her, as it has turned out.

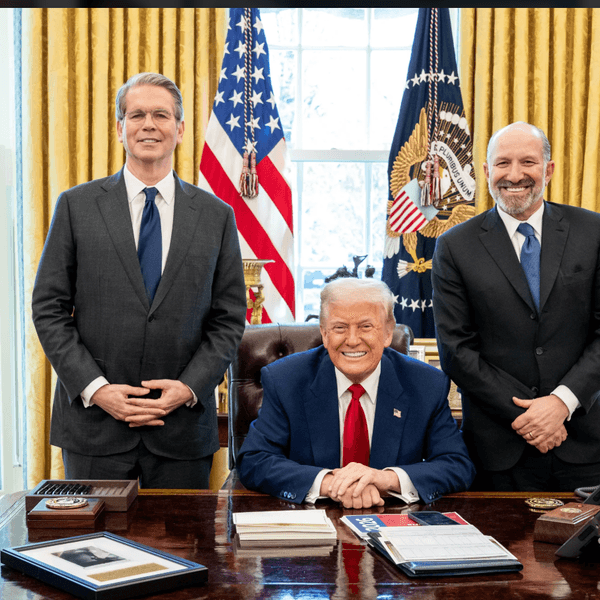

Before we left that evening in 2003, Marcia Grace wanted to stand with us for a picture. In the photo, she is quite the contrast to our tux-and-gown ensemble, standing in lime-green ankle socks as a flowered skirt ruffles around her knees. She is smiling, and we are, too, tucked around her like moonstruck fans.

At the time, I thought it was funny that she wanted the picture. Now I cherish it. The photograph marks the beginning of my life with Marcia Grace in it.

Every merged family needs time to get used to the idea of one another, and ours was no different. Most of us reach middle age pretty set in our ways.

Marcia Grace would have none of that. I married her uncle, and that made me her aunt. Period. She, more than anyone else, helped me fit in.

At first, she was the happy only child who enjoyed being the center of my attention. As she matured, so did her focus. By high school, she was your typical overachiever, except to me there was nothing typical about her. At an early age, she was looking out for others, with an ability to discern who did and didn’t have her advantages. When she started working for her school newspaper, our conversations turned to best practices in journalism. She was interested in all of it — interviewing, confirming, writing and editing, responding to readers.

“OK, one more question,” she’d say, and then she’d rattle off another list of things that were on her mind. Her overarching theme: How do we get people to care?

Living in Shaker Heights, a diverse inner-ring suburb of Cleveland, Marcia Grace became obsessed — I mean that as highest praise — with issues of racial justice. She is a woman of her times. Cleveland is facing a court-ordered overhaul of its police department, which has alienated many black residents with its excessive use of force. Marcia Grace would rightfully object to that phrasing, as she insists that these tragedies in the black community are white citizens’ problem, too.

Which brings me to her graduation this week from Shaker Heights High School, where she gave one of the student speeches. I realize I’m coming off as an insufferably proud aunt. I plead guilty. Marcia Grace has taught me the bone-deep joy my sister Toni and my friend Sue have described to me in their many years as their families’ favorite aunts. You don’t have to be a parent to feel a parent’s pride in a child you love.

But it’s more than familial affection that drives me to write this column about Marcia Grace. Quite simply, I am grateful. She keeps me honest, keeps me trying.

On Tuesday night, she walked to the lectern and spoke for her generation. These young people are something. Our exhaustion bores them. Our apathy appalls them. Yes, they are young and life will whittle away at some of that, but I see in them a commitment to fix what we were supposed to repair.

“We have a common hope that our future will be more inclusive, more compassionate and more daring than that of our parents,” Marcia Grace said. “Whatever we choose to do with our lives, we will have opportunities to be friends to outcasts, mentors to the disadvantaged and lights for the depressed. When those opportunities occur, we must present ourselves for action.”

I’ve known this child for a long time now.

Overnight, she became a woman who fills me with hope.

Again.

—

Connie Schultz is a Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist and an essayist for Parade magazine. She is the author of two books, including …and His Lovely Wife, which chronicled the successful race of her husband, Sherrod Brown, for the U.S. Senate. To find out more about Connie Schultz (con.schultz@yahoo.com) and read her past columns, please visit the Creators Syndicate Web page at www.creators.com.

Photot: Rachel Kramer via Flickr