By Barbara Demick, Los Angeles Times

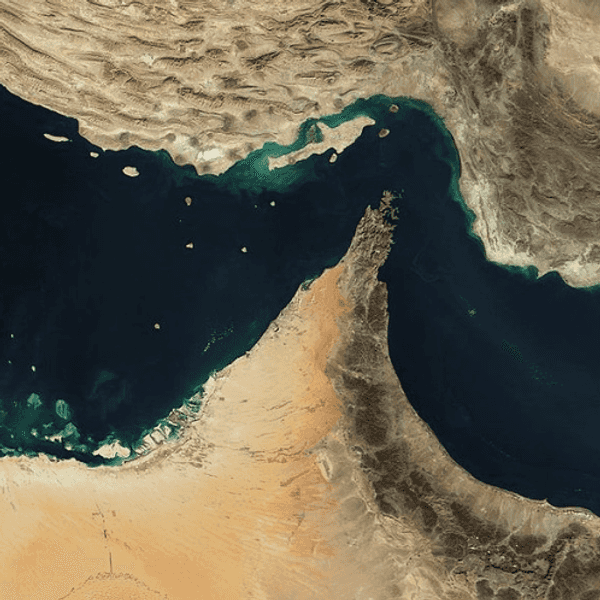

BEIJING — The search and rescue teams working off the west coast of Australia seeking the missing Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 discovered what oceanographers have been warning: Even the most far-flung stretches of ocean are full of garbage.

For the first time since the search focused on the southern Indian Ocean 10 days ago, the skies were clear enough and the waves calm, allowing ships to retrieve the “suspicious items” spotted by planes and on satellite imagery.

But examined on board, none of it proved to be debris from the missing plane, just the ordinary garbage swirling around in the ocean.

“A number of objects were retrieved by HMAS Success and Haixun 01 yesterday,” reported the Australian Maritime Safety Authority in a news release Sunday. “The objects have been described as fishing equipment and other flotsam.”

A cluster of orange objects spotted by a search plane on Sunday drew the same results, the Associated Press reported the following day: It was just fishing equipment.

Using a fresh analysis of flight data, investigators on Friday moved the search location in the southern Indian Ocean 680 miles to the northeast — waters where the currents are weaker but where there is more debris, according to an Australian oceanographer.

It is an oddity in one of the most remote places on the planet, far from any islands, shipping lanes or flight paths.

“You have garbage from Australia, from Indonesia, from India,” said Erik van Sebille, an oceanographer at the University of New South Wales in Sydney. “There are small vortexes that are mixing up the debris like stirring a teacup.”

Science writer Marc Lallanilla has referred to the search for Flight 370 as a “needle in a garbage patch.”

“In addition to foul weather, administrative bungling and the vastness of the search area, the search for MH 370 has been compounded by one other factor: the incredible amount of garbage already floating in the search area — and in oceans worldwide,” Lallanilla wrote on the website livescience.com.

The complicating factor underscored the difficulty the search teams face in trying to find out what happened to the Boeing 777 and its 239 passengers and crew. The plane disappeared March 8 during a flight to Beijing from Kuala Lumpur, the Malaysian capital.

Australian authorities said Sunday that a naval support ship, the Ocean Shield, will depart from Perth on Monday with a “black box detector” supplied by the U.S. Navy. The Towed Pinger Locator 25 carries a device that should be able to detect the so-called black boxes of the plane in waters as deep as 20,000 feet. The boxes record pilots’ conversations and flight data.

The search team is in a race against time because black boxes’ batteries last only 30 to 45 days.

The odds are stacked against finding them in time without a trail of debris to guide searchers. Investigators for now are merely surmising that the plane crashed into the Indian Ocean, based on an analysis of the flight’s path according to engine data transmitted via satellite.

The best-known precedent is the case of Air France Flight 447, which went into the Atlantic on a flight from Rio de Janeiro to Paris in 2009. It took two years to find the body of the aircraft and the black boxes in the ocean depths, though pieces of debris were found on the surface within five days of the crash.

The lack of confirmed debris has prevented families from achieving any kind of closure over the deaths of their relatives. Chinese families, in particular, have rejected the assertion of the Malaysian government that the plane crashed with no survivors.

“We want evidence, truth and dignity,” read banners that Chinese relatives held up Sunday during an impromptu demonstration at a hotel in Kuala Lumpur.

Malaysia Airlines said Sunday that it will fly families of passengers to Perth and will set up a family assistance center to provide counseling and logistical support, but will do so “only once it has been authoritatively confirmed that the physical wreckage found is that of MH 370.”

Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott told reporters Monday that the search would continue.

“Now until we locate some actual wreckage from the aircraft and then do the regression analysis that might tell us where the aircraft went into the ocean, we’ll be operating on guesstimates,” Abbott told reporters at the Pearce air force base near Perth.

Photo: Xinhua/Zuma Press/MCT