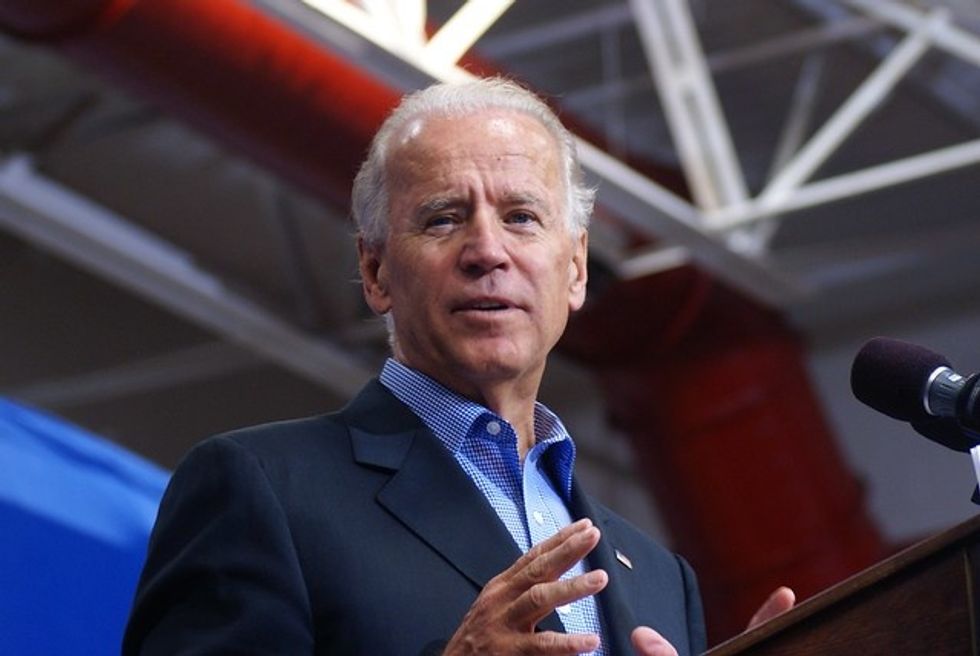

Wrong On Crime? Many Black Americans Agreed With Biden

Cory Booker, Kamala Harris, and other Democratic presidential candidates believe that Joe Biden was wrong in helping to craft and pass the 1994 crime bill, which they blame for the damage it wrought among African Americans.

They have a point. What they fail to grasp is that if they had been senators then, they likely would have been wrong right along with him.

It’s easy in retrospect to see that the legislation was deeply flawed. In fact, it was not impossible to see it even then. I wrote columns at the time criticizing the bill for expanding death penalty crimes, mandating life sentences for repeat offenders (“three strikes and you’re out”) and locking up more criminals for longer periods.

The increase in incarceration that occurred in the 1990s did have a lopsided racial impact. But it was not the product of the crime bill, because the vast majority of felons are prosecuted and imprisoned under state laws. The federal crackdown played only a minor role.

“The proud architect of a failed system is not the right person to fix it,” declares Booker. Most of the provisions in the 1994 bill, however, have already been “fixed,” by expiration or repeal.

The people who opposed the bill had the better of the argument. But to understand the legislation and its broad support in Congress, you have to understand the frightening climate in which it was passed.

Between 1983 and 1992, the violent crime rate jumped by 41 percent. New York City had 2,245 murders in 1990, or more than six per day. Chicago had 943 murders in 1992. (By comparison, New York had 289 homicides last year, and Chicago had 572.) The crack epidemic was in full, terrifying swing.

Americans were keenly aware of the growing danger, and they wanted something done about it — whatever it took to make them safer. There was “a fabulously intemperate and angry mood among Americans,” recalls Franklin Zimring, a criminologist at the University of California, Berkeley. Politicians had to respond.

The crime bill was one response to that mood. It was a big package, including not only the provisions I mentioned before but also money to add 100,000 police nationwide, a ban on “assault weapons,” and inducements for states to lengthen prison terms (“truth in sentencing”). It adopted many Republican policies while helping Democrats shed their soft-on-crime label.

At the time, the racial politics were not quite what you might assume. Prior to becoming mayor of Atlanta in 1990, Maynard Jackson offered a plan to confiscate the property of drug dealers called “Kick Their Assets.”

As for murderers, Washington, D.C., Mayor Marion Barry wanted police to “hunt them down like mad dogs.” Black leaders like these wanted stern action because it was African Americans who were most likely to be harmed by crime.

“At the height of the epidemic, black political and civic leaders often compared crack to the greatest evils that African Americans had ever suffered,” Yale Law professor James Forman Jr., who is black, wrote in his 2017 book Locking Up Our Own. One NAACP official called it “the worst thing to hit us since slavery.”

In his 1997 book, Race, Crime and the Law, Harvard law professor Randall Kennedy, an African American, argued that “blacks have suffered more from being left unprotected or under-protected by law enforcement authorities than from being mistreated as suspects or defendants.”

In many black neighborhoods, one thing scarier than having police around is not having them. The crime bill provided more of them.

Whites who favored punitive action may have been motivated partly by racial prejudice. But black sentiment also helped to produce these policies.

A 1994 Gallup survey found that 58 percent of African Americans supported the crime bill — compared with 49 percent of whites. The only black senator, Carol Moseley Braun of Illinois, supported it. Of the 40 members of the Congressional Black Caucus, just 12 voted against it.

It may seem plausible that black Americans would blame Biden for his role in bringing about the incarceration of so many of their brethren. But that assumes they actually object to this outcome. In a 2014 poll by the Sentencing Project, 64 percent of them said that courts were too lenient in punishing criminals.

A generation ago, Biden made his share of mistakes when it came to fighting crime. If they had been in his place, would Booker or Harris have done better? I wouldn’t bet on it.