Never have so many done so much to reveal so little than in the collected journalism about presidential nomination contests. The personality-driven trivia. The hokey generalizations. The bogs of conventional wisdom. The day-by-day scorekeeping that ends up worse than uninformative; it is anti-informative. (Just ask Presidents George Romney, Edmund Muskie, Scoop Jackson, John Connally, Richard Gephardt, and Hillary Rodham Clinton.) The utter failure to inform the public of the actual, on-the-ground dynamics of the nuts-and-bolts process by which the parties chose their standard-bearers, and the larger dynamics that drive party trends from decade to decade.

And, last but not least, the shameful lack of any useful contribution to a richer public understanding of what any of this means for the future of the republic at large. Consider, to take an example close to hand, the saga of the $80,000 boat.

On June 9, The New York Times ran a useful, detailed consideration of the finances of Marco Rubio. Publicly, the Florida senator describes his everyman’s struggle to “finally pay off his law school loans.” Privately, according to state records unearthed by the paper’s Steve Eder and Michael Barbaro, he spent “$80,000 for a luxury speedboat.”

The detail revealed a larger pattern: Rubio has been financially in the hole for nearly his entire adult life. The reason this mattered, noted the Times—whose work on Rubio has been a welcome exception to the rule of bad campaign reporting—was that it “has made him unusually reliant on a campaign donor, Norman Braman, a billionaire who has subsidized Mr. Rubio’s job as a college instructor, hired him as a lawyer, and continues to employ his wife.”

These details were explained in the Times a month earlier. The same two reporters described the 82-year-old Braman, an almost comically plutocratic figure who sells Rolls Royces and Bugattis for a living, and almost singlehandedly recalled Miami’s mayor. Braman, who implored the Times reporters, “I don’t consider myself a fat cat. Don’t make me out to be a fat cat,” has been able to call the tune for the 44-year-old Rubio.

Then came Politico’s bubble-headed media reporter Dylan Byers with a scoop: Rubio’s “luxury speedboat” was “in fact, an offshore fishing boat.” Speedboats, you see, are for rich swells; fishing boats, even ones costing almost $100,000, are for jes’ folks.

Immediately, this supposed error became the shiny bouncing ball the political media decided to chase.

Politico covered Boatgate eight times over the next two weeks—Byers twice in two consecutive days. They didn’t mention Braman once. (They had mentioned him in May—in scorekeeping mode, as the “Miami auto dealer who’s expected to pour anywhere from $10 million to $25 million into [Rubio’s] bid.”) The Washington Post also featured little but nautically inclined reporting on Rubio in that same period, seven pieces mentioning the boat including one fact checking Jon Stewart and another headlined “Mr. Rubio, Like a Lot of Americans, Is Terrible With Money.” (Not, say, “Mr. Rubio, Like a Lot of Americans, Has a Surrogate Father Who Loans Him Rides on His Private Jet.”) The neocons at The Weekly Standard summed things up for the historical record: The Times’ “failed hit on Marco Rubio’s fishing boat” proved “Rubio is [the] GOP frontrunner.” End of story.

What else do you need to know about Marco Rubio in the second week of June 2015?

Political Science Fail

Political scientists, in their earnest, empirical way, don’t offer much more illumination. The most influential effort is The Party Decides: Presidential Nominations Before and After Reform (University of Chicago Press, 2008). Its co-authors, John Zaller, Marty Cohen, Hans Noel, and David Karol, have been frequently quoted on the subject. Unfortunately, much of what they have to offer is banal.

“Candidates without party support have never won,” Zaller told The New York Times’ Nate Cohn—a water-is-wet sort of insight, and question-begging at that: What about Barry Goldwater, who had so much party “support” that hardly any Republican officeholders campaigned for him in 1964, or George McGovern in 1972, against whom major party figures and factions conspired in the general election?

What this all suggests is that the state-of-the-art statistical mojo conjured over 416 pages by four of the most respected scholars in the field amounts to very little when it comes to predicting who gets nominations and why.

Statisticians routinely warn of what they describe as the “small N” problem: Unless there is enough data to work with, it’s all but impossible to make statistically valid conclusions.

There have been precisely 10 presidential election cycles in the modern period that began with the two parties reforming their nominating systems after 1968, to favor primaries and caucuses open to party rank and file instead of backroom brokering by party elites. That’s not enough data to come up with useful, statistically verifiable conclusions that can be expected to endure—such as the old saw about presidential nominations: “Democrats fall in love. Republicans fall in line.”

That is to say that Dems have ended up choosing sexy outliers who emerge as if from nowhere: George McGovern, Jimmy Carter, Bill Clinton. Republicans, more authoritarian in mien, tab the second-place finisher in the previous contested race, or venerable warhorses, or presidents’ sons.

Today, this pattern appears to be an artifact of a bygone age. As of this writing there are 15* declared candidates. Early polling had Donald Trump in the lead, and not even a stable top tier, as revealed by polling, donations, endorsements, or any other metric you can think of.

Conned by Cohn

So all is chaos? Nate Cohn, venturing one of his trademark analyses that cut through an apparent morass of complexity to reveal the truth hidden within, says not: He argued in April that the Republicans were well on their way to sorting themselves out into a traditional two-way race, a frontrunner (either Bush, Walker, or possibly Rubio) and a rotating cast of colorful second-place flavors of the month, like in 2012. (Pop quiz: who was Herman Cain?) Cohn sorted the Republicans into three buckets, adducing historical antecedents for each. He claimed his argument reveals “underlying fundamentals” that “determine from the very start which candidate will win the nomination.”

He slips upon banana peel after banana peel in the attempt. His first bucket is “Invisible Primary Leaders”—whom he claims almost always win. He cites the Mitt Romneys, the GWB’s, the Al Gores, Walter Mondales—reasonable enough. But he also includes Ronald Reagan, which is nonsense. Running up to 1980, Reagan was the serious candidate least respected by “invisible primary” gatekeeping elites. Their darlings were Howard Baker, George Bush, and, most prominently, “Big John” Connally—who spent $11 million in 1980 to win a single delegate.

“No factor has proved more important to a candidate’s chances than the loyalty of party elites.” Not hardly. Cohn’s article only makes it seem so by excluding such elites of elite darlings as Scoop Jackson in 1976, Humphrey and Muskie in 1972, George Romney in 1968—and I could go on. He goes on to torture the data in such a way that 89 percent of those he lists as “Invisible Primary Winners” went on to become nominees. In my own tally of same, however, the number is more like 45 percent.

I could explore his argument further, but a third of the way through his article, Cohn’s whole foundation has so badly broken down, it hardly matters.

So what indicators should a well-informed citizen be following? Not polls. At this point in 2012 Mitt Romney was running behind Rudy Giuliani, with Sarah Palin close behind. Not even, really, the winners of elections. Who won that year’s Iowa caucus? Rick Santorum. He then carried 10 more states. It ended up not mattering. Republican nominations are not simple plebiscites; the process is much more occult than that.

Don’t pay overmuch attention to the braying loudmouths of the activist right either, as they flay Marco Rubio as a handmaiden of the Mexican hordes for daring to express compassion for immigrants; Ohio governor John Kasich for herding the poor onto the federal plantation by accepting Obamacare’s Medicaid subsidies; Jeb Bush for welcoming brainwashing federal bureaucrats into Florida elementary schools.

Remember they flayed John McCain even worse. Talk-radio host Michael Reagan first noted the “huge gap that separates McCain,” who “has contempt for conservatives who he thinks we can be duped into thinking he’s one of them,” from “my dad, Ronald Reagan.” Eight days later Michael Reagan reconsidered and said, “You can bet my father would be itching to get out on the campaign trail working to elect him.”

Authoritarians follow signals from above. Which won’t keep the puppies of the press corps from dwelling on which candidate the angry Tea Party bleaters are calling “unacceptable” this week, even though that really doesn’t matter.

What about endorsements? For one thing, you’ll have to scour the news to find them. Carly Fiorina may have won the undying devotion of Gene G. Chandler, deputy speaker of the New Hampshire House of Representatives. And have you heard Mike Huckabee has nabbed not just the lieutenant governor of Arkansas, but her secretary of state and state treasurer? But news like that is not particularly useful if you’re a producer or editor hungry for titillated eyeballs. And perhaps that’s for the best. The name of today’s game is TV commercials, not endorsements, door-knocking armies, and “walking around money.” TV is costly and it takes don’t-call-me-fat-cats like Norman Braman, Sheldon Adelson, and the Brothers Koch to pay those kinds of bills.

Next: The Plutocrats’ Right to Choose

The Plutocrats’ Right to Choose

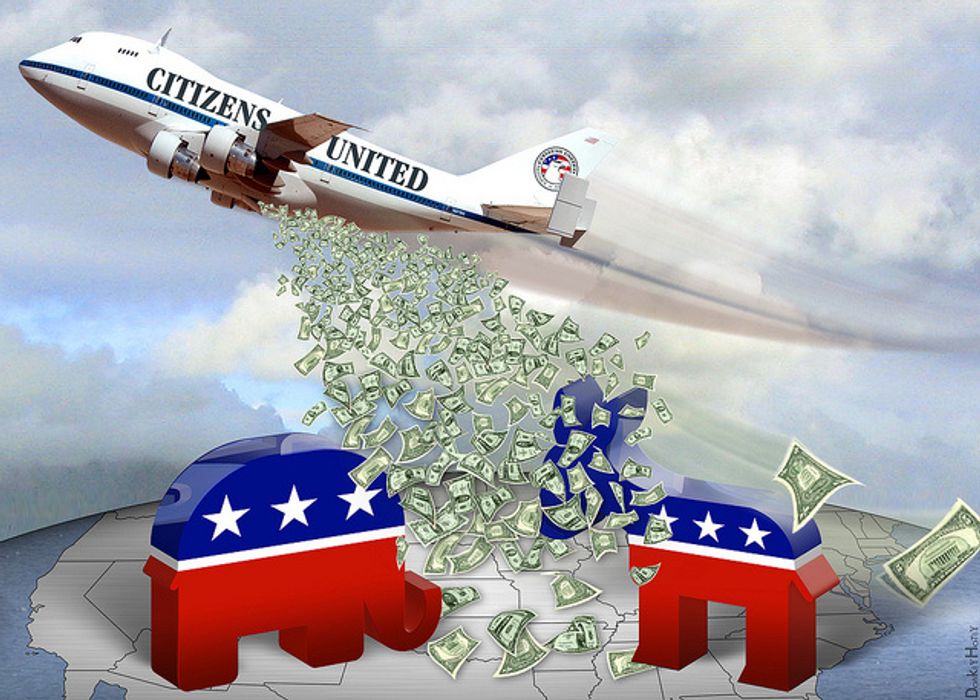

The bottom line is that the penumbras and emanations of Citizens United are changing the campaign game in ways that throw all previous understandings of how Republicans nominate presidents into a cocked hat. To see how it’s working on the ground, come with me to Southern California, where last year David and Charles Koch convened one of their dog-and-pony shows, where the aspirants lined up to stand on their hind legs to beg before their would-be masters. Politico spoke to two people who were there, and offered the following account of the performance of Ohio’s Governor John Kasich.

- “Randy Kendrick, a major contributor and the wife of Ken Kendrick, the owner of the Arizona Diamondbacks, rose to say she disagreed with Kasich’s decision to expand Medicaid coverage, and questioned why he’d said it was ‘what God wanted.’” Kasich’s “fiery” response: “I don’t know about you, lady. But when I get to the pearly gates, I’m going to have to answer what I’ve done for the poor.”

Other years, before other audiences, such public piety might have sounded banal. This year, it’s enough to kill a candidacy:

- “About 20 audience members walked out of the room, and two governors also on the panel, Nikki Haley of South Carolina and Bobby Jindal of Louisiana, told Kasich they disagreed with him. The Ohio governor has not been invited back to a Koch seminar.”

Which is, of course, astonishing. But even more astonishing was the lesson that Politico drew from it—one, naturally, about personalities: “Kasich’s temper has made it harder to endear himself to the GOP’s wealthy benefactors.” His temper. Not their temper. Not, say, “Kasich’s refusal to kowtow before the petulant whims of a couple of dozen greedy nonentities who despise the Gospel of Jesus Christ has foreclosed his access to the backroom cabals without which a Republican presidential candidacy is inconceivable.”

To see how consequential the handing over of this kind of power to non-entities like these is, consider the candidates’ liabilities with another constituency once considered relevant in presidential campaigns: voters. Chris Christie’s home state approval rating, alongside his opening of a nearly billion-dollar hole in New Jersey’s budget, is 35 percent. While Christie has only flirted with federal law enforcement, Rick Perry has been indicted. Scott Walker’s approval rating among the people who know him best (besides David Koch) is 41 percent, and only 40 percent of Wisconsinites believe the state is heading in the right direction. Bobby Jindal’s latest approval rating in the Pelican State is 27 percent. Senator Lindsey Graham announced his presidency by all but promising he’d take the country to war; Jeb Bush by telling Americans they need to work more. Rick Santorum not so long ago made political history: he lost his Senate seat by 19 points, an unprecedented feat for a two-term incumbent.

That political facts this blunt are no longer disqualifying for presidential candidates is a sort of revolution. If the winnowing of frontrunners from also-rans has traditionally been a financial process (when the money dries up, so do the campaigns), Sheldon Adelson of Las Vegas and Macau began tearing up that paradigm in 2012 by shoveling money to Newt Gingrich; $20 million total, including $5 million dispensed on March 23, three days after Gingrich won 8 percent in Illinois’s primary to Mitt Romney’s 47 percent, keeping Gingrich officially in the race more than a week after the RNC declared Romney the presumptive nominee.

Now, four previously unheard-of SuperPACS supporting Ted Cruz, who has no support among the GOP’s “establishment,” raised $31 million “with virtually no warning over the course of several days beginning Monday.” The New York Times reported this shortly after reporting that “[t]he leader of the Federal Election Commission, the agency charged with regulating the way political money is raised and spent, says she has largely given up hope of reining in abuses in the 2016 presidential campaign, which could generate a record $10 billion in spending.”

The Koch brothers, you can learn if you take a deep enough dive into the relatively obscure precincts of campaign coverage, are battling to take over a major function of the Republican National Committee.

And all this, admittedly, gets reported… in bits and pieces. But all this noise doesn’t amount to an ongoing story by which citizens can understand what is actually going on. Not just concerning who might be our next president, but what it all means for the republic. And not just concerning the candidates, but the behind-the-scenes string pullers whose names, really, should be almost as familiar to us as Mr. Bush, Mr. Rubio, and, God forbid, Dr. Carson.

Instead, we get the same old hackneyed horse race—like, did you know that Rick Santorum is in trouble? Only one voter showed up at his June 8 event in Hamlin, Iowa. The Des Moines Registerreported that. Politicomade sure that tout Washington knew it. Though neither mentioned that Santorum is still doing just fine with the one voter who matters: Foster Friess, the Wyoming financier who gave his SuperPAC $6.7 million in 2012, and promises something similar this year. “He has the best chance of winning,” Friess said. “I can’t imagine why anybody would not vote for him.’’ Which, considering only 2 percent of New Hampshirites and Iowans agree with him, is kind of crazy. And you’d think having people like that picking the people who govern us would all be rather newsworthy.

You’d be right.

Just don’t expect to read anything about it in Politico.