Reprinted with permission from TomDispatch

Censoring the News, Big Time

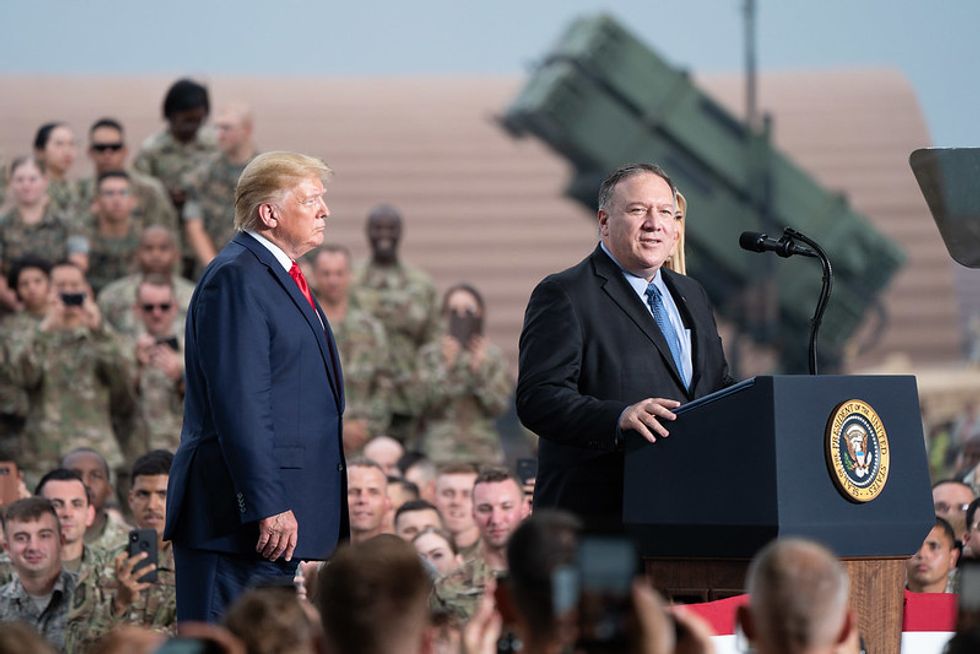

Though few remember it today, exactly 100 years ago, this country’s media was laboring under the kind of official censorship that would undoubtedly thrill both Donald Trump and Mike Pompeo. And yet the name of the man who zestfully banned magazines and newspapers of all sorts doesn’t even appear in either Morison’s history, that Britannica article, or just about anywhere else either.

The story begins in the spring of 1917, when the United States entered the First World War. Despite his reputation as a liberal internationalist, the president at that moment, Woodrow Wilson, cared little for civil liberties. After calling for war, he quickly pushed Congress to pass what became known as the Espionage Act, which, in amended form, is still in effect. Nearly a century later, National Security Agency whistleblower Edward Snowden would be charged under it and in these years he would hardly be alone.

Despite its name, the act was not really motivated by fears of wartime espionage. By 1917, there were few German spies left in the United States. Most of them had been caught two years earlier when their paymaster got off a New York City elevated train leaving behind a briefcase quickly seized by the American agent tailing him.

Rather, the new law allowed the government to define any opposition to the war as criminal. And since many of those who spoke out most strongly against entry into the conflict came from the ranks of the Socialist Party, the Industrial Workers of the World (famously known as the “Wobblies”), or the followers of the charismatic anarchist Emma Goldman, this in effect allowed the government to criminalize much of the Left. (My new book, Rebel Cinderella, follows the career of Rose Pastor Stokes, a famed radical orator who was prosecuted under the Espionage Act.)

Censorship was central to that repressive era. As the Washington Evening Star reported in May 1917, “President Wilson today renewed his efforts to put an enforced newspaper censorship section into the espionage bill.” The Act was then being debated in Congress. “I have every confidence,” he wrote to the chair of the House Judiciary Committee, “that the great majority of the newspapers of the country will observe a patriotic reticence about everything whose publication could be of injury, but in every country there are some persons in a position to do mischief in this field.”

Subject to punishment under the Espionage Act of 1917, among others, would be anyone who “shall willfully utter, print, write or publish any disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive language about the form of government of the United States, or the Constitution of the United States, or the military or naval forces of the United States.”

Who was it who would determine what was “disloyal, profane, scurrilous, or abusive”? When it came to anything in print, the Act gave that power to the postmaster general, former Texas Congressman Albert Sidney Burleson. “He has been called the worst postmaster general in American history,” writes the historian G. J. Meyer, “but that is unfair; he introduced parcel post and airmail and improved rural service. It is fair to say, however, that he may have been the worst human being ever to serve as postmaster general.”

Burleson was the son and grandson of Confederate veterans. When he was born, his family still owned more than 20 slaves. The first Texan to serve in a cabinet, he remained a staunch segregationist. In the Railway Mail Service (where clerks sorted mail on board trains), for instance, he considered it “intolerable” that whites and blacks not only had to work together but use the same toilets and towels. He pushed to segregate Post Office lavatories and lunchrooms.

He saw to it that screens were erected so blacks and whites working in the same space would not have to see each other. “Nearly all Negro clerks of long-standing service have been dropped,” the anguished son of a black postal worker wrote to the New Republic, adding, “Every Negro clerk eliminated means a white clerk appointed.” Targeted for dismissal from Burleson’s Post Office, the writer claimed, was “any Negro clerk in the South who fails to say ‘Sir’ promptly to any white person.”

One scholar described Burleson as having “a round, almost chubby face, a hook nose, gray and rather cold eyes and short side whiskers. With his conservative black suit and eccentric round-brim hat, he closely resembled an English cleric.” From President Wilson and other cabinet members, he quickly acquired the nickname “The Cardinal.” He typically wore a high wing collar and, rain or shine, carried a black umbrella. Embarrassed that he suffered from gout, he refused to use a cane.

Like most previous occupants of his office, Burleson lent a political hand to the president by artfully dispensing patronage to members of Congress. One Kansas senator, for example, got five postmasterships to distribute in return for voting the way Wilson wanted on a tariff law.

When the striking new powers the Espionage Act gave him went into effect, Burleson quickly refocused his energies on the suppression of dissenting publications of any sort. Within a day of its passage, he instructed postmasters throughout the country to immediately send him newspapers or magazines that looked in any way suspicious.

And what exactly were postmasters to look for? Anything, Burleson told them, “calculated to… cause insubordination, disloyalty, mutiny… or otherwise to embarrass or hamper the Government in conducting the war.” What did “embarrass” mean? In a later statement, he would list a broad array of possibilities, from saying that “the government is controlled by Wall Street or munition manufacturers or any other special interests” to “attacking improperly our allies.” Improperly?

He knew that vague threats could inspire the most fear and so, when a delegation of prominent lawyers, including the famous defense attorney Clarence Darrow, came to see him, he refused to spell out his prohibitions in any more detail. When members of Congress asked the same question, he declared that disclosing such information was “incompatible with the public interest.”

One of Burleson’s most prominent targets would be the New York City monthly The Masses. Named after the workers that radicals were then convinced would determine the revolutionary course of history, the magazine was never actually read by them. It did, however, become one of the liveliest publications this country has ever known and something of a precursor to the New Yorker. It published a mix of political commentary, fiction, poetry, and reportage, while pioneering the style of cartoons captioned by a single line of dialogue for which the New Yorker would later become so well known.

From Sherwood Anderson and Carl Sandburg to Edna St. Vincent Millay and the young future columnist Walter Lippmann, its writers were among the best of its day. Its star reporter was John Reed, future author of Ten Days That Shook the World, a classic eyewitness account of the Russian Revolution. His zest for being at the center of the action, whether in jail with striking workers in New Jersey or on the road with revolutionaries in Mexico, made him one of the finest journalists in the English-speaking world.

A “slapdash gathering of energy, youth, hope,” the critic Irving Howe later wrote, The Masses was “the rallying center… for almost everything that was then alive and irreverent in American culture.” But that was no protection. On July 17, 1917, just a month after the Espionage Act passed, the Post Office notified the magazine’s editor by letter that “the August issue of the Masses is unmailable.” The offending items, the editors were told, were four passages of text and four cartoons, one of which showed the Liberty Bell falling apart.

Soon after, Burleson revoked the publication’s second-class mailing permit. (And not to be delivered by the Post Office in 1917 meant not to be read.) A personal appeal from the editor to President Wilson proved unsuccessful. Half a dozen Masses staff members including Reed would be put on trial — twice — for violating the Espionage Act. Both trials resulted in hung juries, but whatever the frustration for prosecutors, the country’s best magazine had been closed for good. Many more would soon follow.

No More “High-Browism”

When editors tried to figure out the principles that lay behind the new regime of censorship, the results were vague and bizarre. William Lamar, the solicitor of the Post Office (the department’s chief legal officer), told the journalist Oswald Garrison Villard, “You know I am not working in the dark on this censorship thing. I know exactly what I am after. I am after three things and only three things – pro-Germanism, pacifism, and high-browism.”

Within a week of the Espionage Act going into effect, the issues of at least a dozen socialist newspapers and magazines had been barred from the mail. Less than a year later, more than 400 different issues of American periodicals had been deemed “unmailable.” The Nation was targeted, for instance, for criticizing Wilson’s ally, the conservative labor leader Samuel Gompers; the Public, a progressive Chicago magazine, for urging that the government raise money by taxes instead of loans; and the Freeman’s Journal and Catholic Register for reminding its readers that Thomas Jefferson had backed independence for Ireland. (That land, of course, was then under the rule of wartime ally Great Britain.) Six hundred copies of a pamphlet distributed by the Intercollegiate Socialist Society, Why Freedom Matters, were seized and banned for criticizing censorship itself. After two years under the Espionage Act, the second-class mailing privileges of 75 periodicals had been canceled entirely.

From such a ban, there was no appeal, though a newspaper or magazine could file a lawsuit (none of which succeeded during Burleson’s tenure). In Kafkaesque fashion, it often proved impossible even to learn why something had been banned. When the publisher of one forbidden pamphlet asked, the Post Office responded: “If the reasons are not obvious to you or anyone else having the welfare of this country at heart, it will be useless… to present them.” When he inquired again, regarding some banned books, the reply took 13 months to arrive and merely granted him permission to “submit a statement” to the postal authorities for future consideration.

In those years, thanks to millions of recent immigrants, the United States had an enormous foreign-language press written in dozens of tongues, from Serbo-Croatian to Greek, frustratingly incomprehensible to Burleson and his minions. In the fall of 1917, however, Congress solved the problem by requiring foreign-language periodicals to submit translations of any articles that had anything whatever to do with the war to the Post Office before publication.

Censorship had supposedly been imposed only because the country was at war. The Armistice of November 11, 1918 ended the fighting and on the 27th of that month, Woodrow Wilson announced that censorship would be halted as well. But with the president distracted by the Paris peace conference and then his campaign to sell his plan for a League of Nations to the American public, Burleson simply ignored his order.

Until he left office in March 1921 — more than two years after the war ended — the postmaster general continued to refuse second-class mailing privileges to publications he disliked. When a U.S. District Court found in favor of several magazines that had challenged him, Burleson (with Wilson’s approval) appealed the verdict and the Supreme Court rendered a timidly mixed decision only after the administration was out of power. Paradoxically, it was conservative Republican President Warren Harding who finally brought political censorship of the American press to a halt.

A Hundred Years Later

Could it all happen again?

In some ways, we seem better off today. Despite Donald Trump’s ferocity toward the media, we haven’t — yet — seen the equivalent of Burleson barring publications from the mail. And partly because he has attacked them directly, the president’s blasts have gotten strong pushback from mainstream pillars like the New York Times, the Washington Post, and CNN, as well as from civil society organizations of all kinds.

A century ago, except for a few brave and lonely voices, there was no equivalent. In 1917, the American Bar Association was typical in issuing a statement saying, “We condemn all attempts… to hinder and embarrass the Government of the United States in carrying on the war… We deem them to be pro-German, and in effect giving aid and comfort to the enemy.” In the fall of that year, even the Times declared that “the country must protect itself against its enemies at home. The Government has made a good beginning.”

In other ways, however, things are more dangerous today. Social media is dominated by a few companies wary of offending the administration, and has already been cleverly manipulated by forces ranging from Cambridge Analytica to Russian military intelligence. Outright lies, false rumors, and more can be spread by millions of bots and people can’t even tell where they’re coming from.

This torrent of untruth flooding in through the back door may be far more powerful than what comes through the front door of the recognized news media. And even at that front door, in Fox News, Trump has a vast media empire to amplify his attacks on his enemies, a mouthpiece far more powerful than the largest newspaper chain of Woodrow Wilson’s day. With such tools, does a demagogue who loves strongmen the world over and who jokes about staying in power indefinitely even need censorship?

Adam Hochschild, a TomDispatch regular, teaches at the Graduate School of Journalism, University of California at Berkeley. He is the author of 10 books, including King Leopold’s Ghost and Spain in Our Hearts: Americans in the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939. His latest book, just published, is Rebel Cinderella: From Rags to Riches to Radical, The Epic Journey of Rose Pastor Stokes.

Follow TomDispatch on Twitter and join us on Facebook. Check out the newest Dispatch Books, John Feffer’s new dystopian novel (the second in the Splinterlands series) Frostlands, Beverly Gologorsky’s novel Every Body Has a Story, and Tom Engelhardt’s A Nation Unmade by War, as well as Alfred McCoy’s In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power and John Dower’s The Violent American Century: War and Terror Since World War II.

Copyright 2020 Adam Hochschild